By Rod Mickleburgh

At long last, a formal apology has been delivered in the House of Commons for Canada’s racist behaviour in its shameful treatment of Sikh passengers aboard the Komagata Maru, who had the effrontery to seek immigration to the West Coast more than a hundred years ago. Not only were they denied entry, they were subjected to two months of exceptionally inhumane treatment by unflinching immigration officers. While many now know the basics of the ill-fated voyage, the story has many elements that are less well known. I am indebted in writing about it to Hugh Johnston and his definitive book, The Voyage of the Komagata Maru.

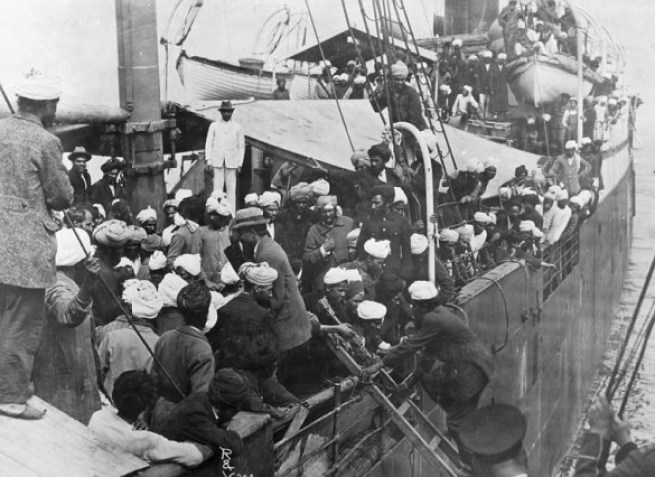

Just days before the outbreak of World War One, the most direct challenge to Canada’s racist, anti-Asian immigration policies was about to come to a potentially bloody end in the waters of Burrard Inlet. Thousands of Vancouverites lined the waterfront to watch, while dozens of small boats bobbed about offshore for a ringside view. All eyes focused on the Komagata Maru, an ungainly Japanese merchant ship carrying more than 350 hungry and increasingly desperate immigrant hopefuls from India, and the HMCS Rainbow, the only seaworthy vessel in the Canadian Navy.

The cruiser had been dispatched after the predominantly Sikh passengers resisted a deportation order by bombarding police trying to board their ship with rocks, bricks and other debris. As the Rainbow trained its guns on the Komagata Maru, those on board bolstered their spirits with patriotic war songs from their Punjabi homeland and prepared for further battle. They vowed to fight to the end. The presence of 200 armed militia gathered on the pier and 35 riflemen aboard a nearby police tug added to the tension.

By then a familiar sight to Vancouverites, the Komagata Maru had been marooned in the harbour for two months by a nasty, hard-boiled immigration agent, Malcolm Reid. An implicit believer in a “white Canada,” Reid took the law into his own hands to ensure not a single immigrant made it to shore. In this, he was actively assisted by local Conservative MP and white supremacist, Henry Herbert Stevens. Now, Reid had a deportation order to force the ship back to Asia. Except those on board were not prepared to leave. The looming showdown and potential of armed conflict so close to shore was a magnet for the people of Vancouver. As chronicler Hugh Johnston put it: “The city had taken the day off to see the show.”

The saga of the Komagata Maru was yet another dark chapter in Canada’s racist past. A complex tale, with many twists and turns, multiple agendas and bitter factionalism, the basic issue was nevertheless straightforward. Among a series of race-based policies to curtail Asian immigration, Canada imposed its harshest restrictions on people from India. Orders-in-council in 1908 brought a complete halt to an immigration flow that had seen 2,500 Indians come to B.C. in less than five years. Though newspapers universally labelled them “Hindus,” almost all were Sikhs from rural Punjab. They proved tough, able workers, finding jobs mostly in logging and sawmills. At the same time, they suffered the same prejudice, harassment and white hysteria as immigrants from China and Japan.

Unlike the Chinese and Japanese, however, who mostly suffered in silence, those from India loudly protested the government’s immigration restrictions.

Arguing they had the same rights as all British subjects, they fought numerous and sometimes successful battles in the courts. In 1914, they took the government head on with the arrival of the Komagata Maru. Organized by Gurdit Singh, an ultra-confident Sikh businessman, the ship and its passengers defied the government’s ordinance that barred Indian immigrants from landing in Canada unless they came on a direct journey from India. No such passage existed. Singh boldly picked up passengers in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Yokohama, before heading to to Vancouver. His aim was to test the ban in court, confident their rights as British subjects would be upheld.

When the ship arrived on May 23, however, Reid refused to allow it to dock. He, too, had a goal: force the Komagata Maru back to Asia, if he could, without a court hearing. To that end, he kept the passengers imprisoned, their ship circled day and night by armed patrol launches. Ignoring instructions from faraway superiors in Ottawa, he stretched normally swift procedures into weeks. And periodically, he cut off food and water deliveries to the ship. At one point, passengers were so thirsty that some licked water off the deck when a small amount spilled from a barrel.

Their fight was taken up by Sikhs on shore, who provided extraordinary support for those on board. The Sikhs’ determined Shore Committee raised thousands of dollars from their relatively small community to pay for lawyers, ship supplies and expenses of the charter, itself. They kept up a barrage of pressure, until at last Ottawa over-ruled the obstreperous Reid and agreed to submit the matter to the B.C. Court of Appeal. With nothing approaching a Charter of Rights and Freedom, however, the five judges ruled unanimously that the ship’s passengers should be deported. Worn out by their many frustrating weeks at sea, those on board accepted the verdict.

Yet Reid, sensing Indian plots everywhere, continued to harass them, ordering the ship to leave without provisions and demanding its huge charter costs be paid first. The vessel remained at anchor, prompting Reid to cut off food and water for three more days. When he foolhardily came on board, the passengers threatened to keep him there. A tall, dignified Sikh told Reid: “If you were starving for three or four hours, you would soon take action to get something for yourself, but we have had nothing for three days. Now you are here, we would like to hold you until we get provisions and water.” The action worked, and supplies soon appeared. The passengers fought back again, when police subsequently tried to board the ship to send it on its way, still without adequate food. That battle brought in the navy, and that brought thousands of excited onlookers to the docks.

The hours ticked by. On the HMCS Rainbow, Commander Walter Hose warned authorities there could be heavy loss of life, if he were ordered to storm the Komagata Maru. Finally, much to the disappointment of the watching crowd and Malcolm Reid, the federal government blinked. They agreed to fully stock the ship for its return journey. At 5 a.m. the next morning, two months to the day of its arrival, the Komagata Maru weighed anchor and headed back to Asia. Racism had triumphed.

Tragically, this was not the end of the story. When the ship reached India, British authorities tried to force passengers directly back to the Punjab. When some resisted, imperial forces opened fire, killing 20 of them at an obscure railway depot named Budge Budge.

And back in Vancouver, bitterness erupted over the role of community informers used by Reid to keep tabs on the situation. Two informers were fatally shot. Shortly afterwards, Reid’s chief Sikh informant opened fire himself at the funeral of one of the victims, killing two worshipers. When Immigration Inspector William Hopkinson, who headed surveillance activities for Reid, showed up at the courthouse, local Sikh Mewa Singh took out a .32 calibre revolver and shot him dead. Before being hung for Hopkinson’s murder, Singh said he acted to uphold the principles and honour of his religion.

To this day, Singh is recognized as a martyr by many in the Sikh community.