The human habitation of the islands across the Pacific Ocean was followed by waves of faunal extinctions that occurred so quickly that their dynamics are difficult to reconstruct in space and time. These extinctions included large, wingless birds called moas that were endemic to New Zealand. In a new study, scientists from the University of Adelaide and elsewhere reconstructed the range and extinction dynamics of six moa species across New Zealand. They found that the final populations of all moa species persisted in cool mountain areas that were generally the last and least affected by humans. They also found that these refuges for the last moa populations continue to serve as isolated refuges for New Zealand’s flightless birds.

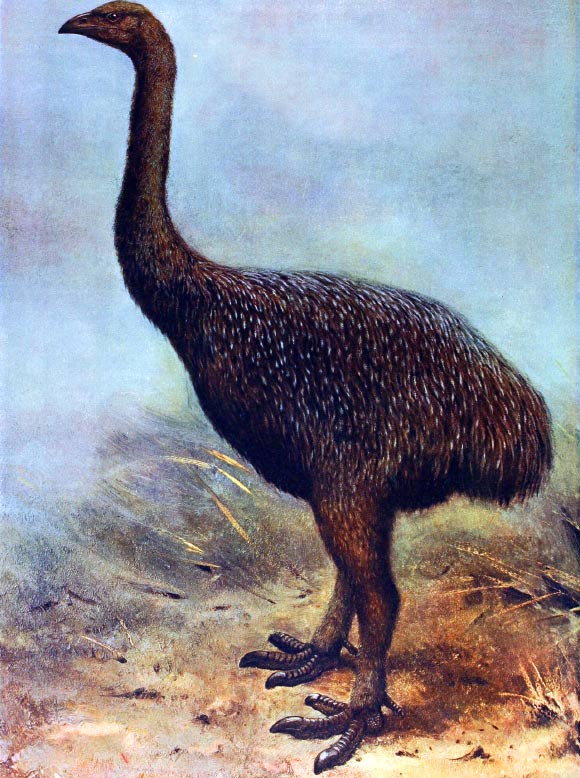

This is an artist’s impression of Moa Upland, Megalapteryx didinusby George Edward Lodge, 1907.

“Our research overcame past logistical challenges to track the population dynamics of six moa species at resolutions not previously considered possible,” said Dr. Damien Fordham of the University of Adelaide.

“We did this by combining sophisticated computational models with extensive fossil records, paleoclimate information and innovative reconstructions of human colonization and expansion across New Zealand.”

“Our research shows that despite large differences in ecology, demography and timing of extinction of moa species, their distributions collapsed and converged on the same areas in the North and South Islands of New Zealand.”

Dr. Fordham and colleagues found that the final populations of all moa species persisted in the same isolated, cold, mountainous environments that today house many of the last populations of New Zealand’s most threatened flightless birds. These include Mount Aspiring in the South Island and the Ruahine Range in the North Island.

Haast’s eagle (Hieraaetus moorei) attacking two moa. Image credit: John Megahan / PLoS Biology, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030020.

“Moa populations likely disappeared first from the lower, higher quality habitats preferred by Polynesian colonists, with rates of population decline decreasing with altitude and distance traveled inland,” said Dr. Sean Tomlinson, also from the University of Adelaide.

“By pinpointing recent populations of moa and comparing them to the distributions of New Zealand’s living flightless birds, we found that these last havens harbor many of today’s persistent populations of takahē, weka and kiwi. big spotted.”

“Furthermore, these ancient refugia for moa overlap with recent mainland populations of critically endangered kākāpō.”

“Although the recent drivers of the decline of New Zealand’s native flightless birds are different from those that caused the moa’s ancient extinction, this research shows that their spatial dynamics remain similar.”

Moa browsed trees and shrubs within the forest floor. Image credit: Heinrich Harder.

“The main commonality between past and present refuges is not that they are optimal habitats for flightless birds, but that they continue to be the last and least affected by humanity,” said Dr. Jamie Wood, also from the University of Adelaide.

“Like earlier waves of Polynesian expansion, habitat conversion by Europeans across New Zealand and the spread of the animals they brought was directional, progressing from lowland areas to less hospitable, cold, mountainous regions.”

The results of the team appear in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

_____

S. Tomlinson et al. The ecological dynamics of moa extinctions reveal a convergent refuge that today hosts flightless birds. Nat Ecol Evol, published online July 24, 2024; doi: 10.1038/s41559-024-02449-x