ATN Belarus

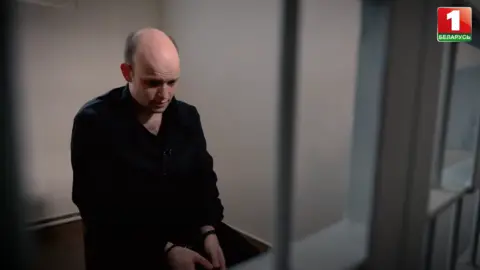

ATN BelarusA German man who has been sentenced to death in Belarus for terrorism has been shown in a heavily choreographed interview on state-controlled television, apparently confessing to planting explosives near a railway line.

There is no direct evidence of that in the 16-minute video for which Rico Krieger was filmed, handcuffed, through the metal bars of an oddly pristine and empty cell.

He says he was acting on instruction from Ukraine, though no proof is given.

Krieger is then shown in tears appealing to the German government for help “before it’s too late”.

He is believed to be the first Western citizen ever given the death penalty in Belarus, which is carried out by firing squad.

Pressure campaign

The emotional and crudely produced video on state TV appears to be part of a campaign of increasing pressure in talks with the German authorities, which some believe may focus on a possible prisoner exchange.

State media say Rico Krieger has not appealed against the verdict, which is extremely rare for someone sentenced to death.

“I’m very surprised,” said Andrei Paluda, a Belarusian campaigner against the death penalty. “I don’t know the circumstances, I can only surmise. But maybe he’s been promised that consultations are ongoing and there might be some kind of swap.”

The unprecedented nature of the case has prompted speculation about links to efforts by Russia, a close ally of Belarus, to free an FSB hitman imprisoned in Germany for the 2019 murder in Berlin of a Chechen-Georgian who fought against Russia.

The deputy spokeswoman for the German foreign ministry declined to comment on such rumours. She also pointed to a history in Belarus of filming staged interviews with prisoners, including opposition activists forced to make confessions to secure their release.

The ministry told the BBC that it was working “intensively” with the Belarusian authorities on behalf of “the person concerned” in this case, but gave no more details citing privacy reasons.

It condemned the death penalty as a “cruel and inhumane form of punishment”.

Last week in Minsk, a foreign ministry spokesman confirmed that a German citizen had been convicted of “terrorism” and “mercenary activity”.

Anatoly Glaz said “a number of options” had been proposed to Berlin, adding that “consultations” were under way.

Who is Rico Krieger?

Rico Krieger/ LinkedIn

Rico Krieger/ LinkedInA profile for Rico Krieger on the LinkedIn platform includes an application for a job in the USA posted last year.

There, he described himself as a 29-year-old Red Cross paramedic from Berlin who had previously worked in security for the US embassy.

He mentioned plans to emigrate to the US and said he had applied for a passport.

A US State Department spokesperson has confirmed to the BBC that Krieger worked for Pond Security, a firm offering security services to US facilities in Germany, between 2015 and 2016. The company itself declined to comment, citing “diplomatic efforts” and privacy.

The German Red Cross also confirmed that Rico Krieger had worked “in the past” for “a district association” of the organisation. A spokesman mentioned his “great concern”, but added that the Red Cross had been told not to comment.

In this story, there are precious few incontrovertible facts.

Officials in Belarus either don’t reply, or reply that they will say nothing – not even to confirm the precise charges.

That may be at least partly due to the political sensitivities. It’s also standard practice in cases involving the death penalty, highly secretive in this authoritarian state.

Few facts, sudden fuss

“I will give you no information,” Vladimir Gorbach, the lawyer who represented Krieger in court, told me by phone. Then he added: “Watch Belarusian official TV. It’s all written there.”

Rico Krieger’s trial appears to have concluded in June. But state-controlled media were silent about this case for weeks. Independent journalists are mostly in exile now, or in prison.

But now it seems information has been fed to faithful state reporters and the order to make a noise has been given.

On Monday, state TV journalist Ludmilla Gladkaya wrote that Krieger had been found guilty on six counts, including an act of terrorism and intentional damage to communication lines.

Citing court documents which the BBC has not been able to obtain, she claimed he had applied to join the Kalinovsky Regiment, founded by Belarusians to fight in Ukraine and designated a “terrorist group” in Belarus.

The journalist claims Krieger was following instructions from the regiment – as well as from Ukraine’s SBU security service – as some kind of initiation process, including in planting the explosives.

The SBU won’t comment, while the Kalinovsky regiment told me only: “He is not our fighter.”

When Belarusian state TV presented its own case – labelling its film the “confession” of a “German terrorist” – it didn’t prove any link to the regiment either.

It showed no communication with the Kalinovsky Regiment.

Instead it displayed screenshots from encrypted email messages which it said were Krieger seeking to sign up with other foreign units in Ukraine. One is supposedly to the II International Legion but a spokesperson there tells me the address is false.

“Perhaps it was created specially for fishing [sic] or something,” they wrote, calling it an act of “fraudulence”.

Oddities and inconsistencies

There are multiple other oddities about this case.

We’ve never heard of foreign volunteers in Ukraine being required to perform “tests” as part of their recruitment, let alone something so risky as set a bomb in Belarus.

There are precious few Western tourists in the country these days. Rico Krieger was never going to blend into the background.

In the propaganda film, he claims he was motivated by the high pay offered to fight in Ukraine. But he then says the monthly salary is around €2,000 (£1,680), less than he was being paid in Germany.

Whilst Krieger writes in good English on LinkedIn, messages attributed to him in the film are barely literate. One reads: “I can’t find the address that me Was given”.

And at one point, the film displays a photo of Krieger from his LinkedIn account. But it’s been doctored, with a Ukrainian flag added to the background for extra impact.

Unrevealing surveillance

Ludmilla Gladkaya’s article tallies with Krieger’s “confession” for the state TV cameras: that he photographed military sites and railway lines for a handler in Ukraine and was then directed to a rucksack hidden in long grass.

He was told to take it to a railway station in Azyaryshcha, east of Minsk, and leave it by the rails. Later that night there was an explosion – but no casualties.

The following day Krieger was arrested.

The journalist quotes his statements on arrest, refers to data from his phone and witnesses including a taxi driver. But no independent information has emerged about any evidence.

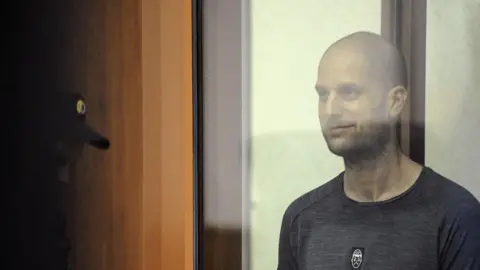

There are certainly CCTV images of Krieger arriving at Minsk airport last October. They show the German smiling at passport control, apparently relaxed. He’s travelling alone and only has hand luggage.

But no surveillance footage of him planting explosives, or acting suspiciously, has been released.

There are just shots of Krieger entering Minsk’s main railway station, and then standing on the platform of an unidentified regional train station, in broad daylight.

A bargaining chip?

Reuters

ReutersThe timing of this case seems significant.

The “noise” erupted just after the US journalist Evan Gershkovich was found guilty of espionage in Russia, a charge his friends and employers denounce emphatically as false. He’s been sentenced to 16 years.

Vladimir Putin has hinted in the past that he would consider exchanging Gershkovich – and possibly others – for Vadim Krasikov, the FSB assassin imprisoned in Germany. But months on, no deal has yet been done.

So could Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko be riding to his rescue – with a German bargaining chip?

The propaganda film is definitely heavy on threat. It has a doom-laden voiceover and threatening scenes acted out by men in balaclavas and with truncheons.

At the centre of it all is a man begging for his life.

In tears, Rico Krieger says he has made the “worst mistake” ever and now feels “absolutely abandoned” by his government. His words seem scripted, though the emotion is raw.

“His only chance now is to ask for a pardon – and for the president to change the death penalty to life in prison,” activist Andrei Paluda said.

“We know of cases when political mechanisms, not legal ones, have come into play. Perhaps that can work here, too.”