A surprising technique has helped scientists observe how the Earth’s oceans are changing, and it’s not using specialized robots or artificial intelligence. It is the labeling of seals.

Several species of seals live around and in Antarctica and regularly dive more than 100 meters in search of their next meal. These seals are experts at swimming through the powerful ocean currents that make up the Southern Ocean. Their tolerance for deep water and ability to navigate rough currents make these adventurous creatures the perfect research assistants to help oceanographers like my colleagues and I study the Southern Ocean.

Seal sensors

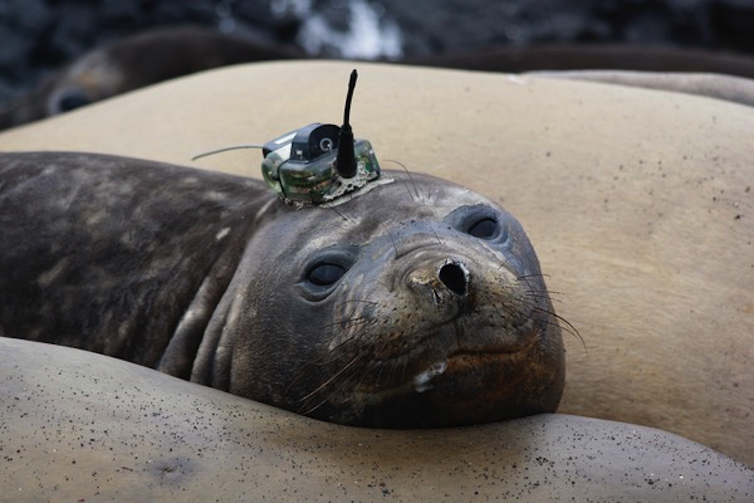

Researchers have been placing tags on the foreheads of seals for the past two decades to gather data in remote and inaccessible regions. A researcher tags the seal during mating season, when the marine mammal comes ashore to rest, and the tag stays attached to the seal for a year.

A researcher attaches the tag to a seal’s head – tagging seals does not affect their behavior. The tag comes off as the seal molts and sheds its fur for a new coat each year.

The tag collects data as the seal dives and transmits location and scientific data to researchers via satellite when the seal surfaces for air.

Etienne Pauthenet

First proposed in 2003, seal tagging has grown into an international collaboration with rigorous sensor accuracy standards and extensive data sharing. Advances in satellite technology now allow scientists to have near-instant access to data collected by a seal.

New scientific discoveries helped by seals

Tags attached to seals typically carry pressure, temperature and salinity sensors, all properties used to gauge rising ocean temperatures and changing currents. The sensors also often contain chlorophyll fluorometers, which can provide data on the phytoplankton concentration of the water.

Christophe Guinet

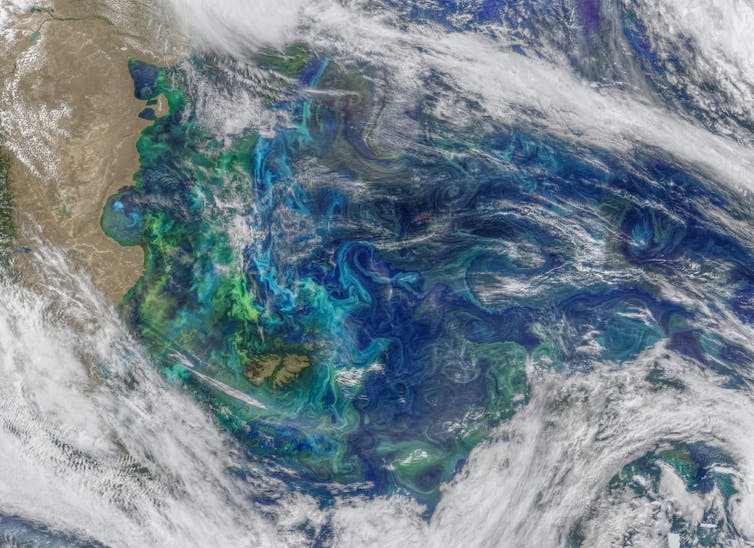

Phytoplankton are tiny organisms that form the base of the oceanic food web. Their presence often means that animals such as fish and seals are around.

The seal’s sensors can also tell researchers about the effects of climate change around Antarctica. Approximately 150 billion tons of ice melts from Antarctica each year, contributing to global sea level rise. This melting is driven by warm water transported to the ice shelves by ocean currents.

With data collected from the seals, oceanographers have described some of the physical paths this warm water travels to reach the ice shelves and how currents transport the resulting melt away from the glaciers.

Seals regularly dive under sea ice and near the ice shelves of glaciers. These regions are challenging and can even be dangerous to sample with traditional oceanographic methods.

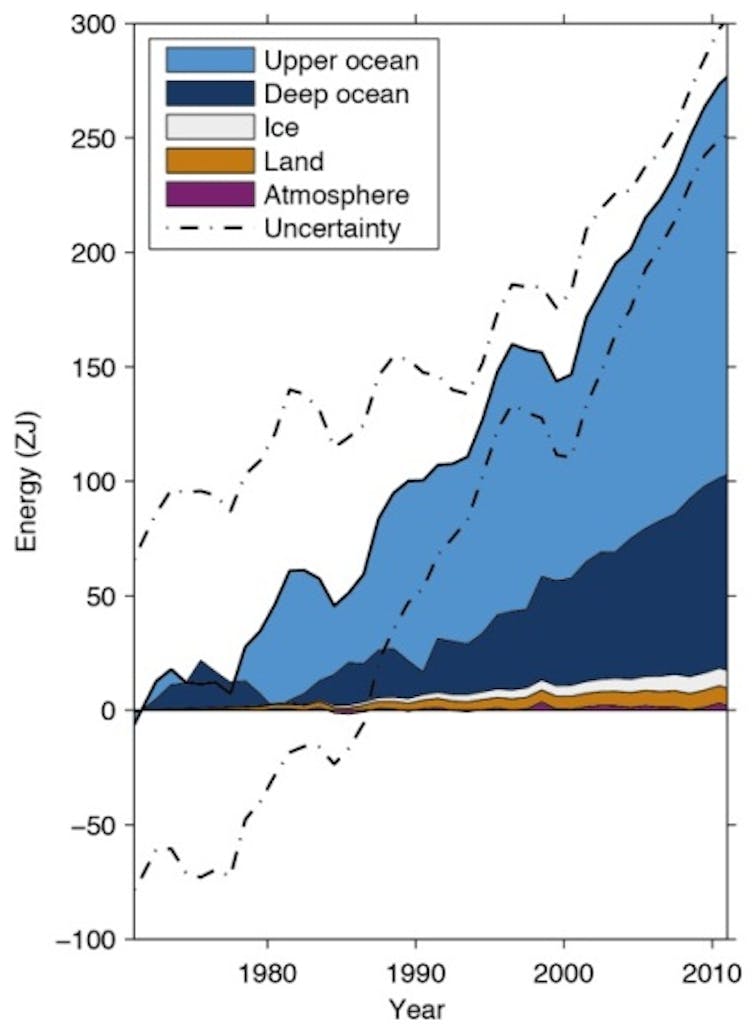

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Across the open Southern Ocean, off the Antarctic coast, seal data has also shed light on another pathway causing ocean warming. Excess heat from the atmosphere moves from the surface ocean, which is in contact with the atmosphere, to the interior ocean in very localized regions. In these areas, heat moves into the deep ocean, where it cannot be dissipated through the atmosphere.

The ocean stores most of the thermal energy put into the atmosphere by human activity. So understanding how this heat moves helps researchers monitor oceans around the globe.

Seal behavior shaped by ocean physics

Seal records also provide marine biologists with information about the seals themselves. Scientists can determine where seals forage. Certain regions, called fronts, are hotspots for elephant seals to hunt for food.

At fronts, ocean circulation creates turbulence and mixes the water in a way that brings nutrients to the surface of the ocean, where phytoplankton can use them. As a result, the fronts can have phytoplankton blooms, which attract fish and seals.

NASA

Scientists use tag data to see how seals are adapting to a changing climate and warming ocean. In the short term, seals may benefit from more ice melting around the Antarctic continent, as they tend to find more food in coastal areas with holes in the ice. However, rising subsurface ocean temperatures could change where their prey is and ultimately threaten the seals’ ability to thrive.

Seals have helped scientists understand and observe some of the most remote regions on Earth. On a changing planet, seal tag data will continue to provide observations of their ocean environment, which has vital implications for the rest of Earth’s climate system.