Edina Slayter-Engelsman lived in Scotland for more than 30 years, but last month the Dutch national returned to the country of her birth to end what she describes as the “unbearable suffering” she had experienced living with severe ME.

The 57-year-old went back to The Netherlands – where euthanasia and assisted suicide are legal for citizens under strict controls – to end her life in what she described as an “off-ramp” from her suffering.

Before Edina died, her family approached BBC Scotland News to share her experience, in the hope of raising awareness of the lack of research and support for people with Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) in Scotland.

The condition, also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), is believed to affect at least 250,000 people in the UK, with the symptoms varying from mild to severe like Edina’s.

There is no known cause or cure for the condition, with treatment only available for specific symptoms.

Warning: Some people might find this article upsetting.

Individual symptoms of ME vary widely but extreme tiredness is a common factor.

NHS guidelines identify four levels of severity from mild, where patients can carry out some domestic tasks, to severe, where patients are unable to get out of bed and can need help feeding.

Research has suggested that one in four people with the condition report they have its most severe symptoms.

In video messages recorded before her death, Edina- who formerly lived in Aberdeenshire – described the most extreme symptoms which left her unable to leave her bed even to shower or use the bathroom.

She was diagnosed with the condition in February 2020 and within a few weeks, she was bedbound.

Four years later, in the videos from her new home in Almere, near Amsterdam, she described it as like being stuck inside a spider’s web.

She said: “Every time you try to get out, the web just gets tighter and tighter around you.”

Before she was ill, Edina was a keen hillwalker, cyclist and swimmer.

“This disease has taken everything from me, she said.

“I feel trapped physically, cognitively and emotionally.

“I exist but I don’t live and this condition has become unbearable to me and has been for a long time now, to the point where I want to end my life.”

She said: “I am isolated from the world outside but also from my own family and friends.

“I am very sensitive to sound, noise, any kind of stimulation, so I can’t really have any kind of get together.

“I have not been able to read books, or watch telly – everything is too much.”

In 2023 Edina returned to the Netherlands to begin a year of psychological and psychiatric assessments, as well as an assessment by Amsterdam’s institute of chronic fatigue.

They concluded there were no other treatment options for her.

So Edina got her wish to end her suffering.

With her husband, two sons and close family beside her – doctors administered a lethal injection which ended her life.

The Netherlands has some of the most liberal laws in the world on assisted dying.

Under strict criteria, it allows voluntary euthanasia for patients experiencing “unbearable suffering with no prospect of improvement”.

This is a relatively recent extension to the Dutch laws on assisted dying and there are opponents who have raised the alarm that it might be a “slippery slope” to include more diagnoses.

While other countries restrict cases to patients with late-stage terminal illnesses, who were of sound mind, there are concerns that the Dutch laws could include those who might otherwise live for many years, such as mentally ill young people.

In Scotland, assisted suicide and euthanasia are currently illegal but a bill has been proposed to allow terminally ill people to end their lives in certain circumstances.

The bill proposed from Lib Dem MSP Liam McArthur is very different to the Dutch law and would be limited to adults who are dying of a terminal illness – not those suffering from a severe long-term condition.

It would not be available to someone like Edina whose condition is not a terminal illness.

The bill will be debated in the Scottish Parliament soon.

For Edina, the recognition of the extent of her suffering by the Dutch medics was “a great achievement”.

“A recognition that there are no further treatment options available to me, there is no cure for CFS and that sense of recognition and relief, it means so much to me and my family,” she says.

“On the one hand I am very sad about this of course, but on the other hand I feel a huge sigh of relief that I am allowed to die with dignity.”

Research suggests that women are significantly more likely to become ill with ME/CFS than men.

Scientists at Edinburgh University are carrying out the world’s largest study of the causes of ME.

DecodeME is examining the DNA of 20,000 participants to investigate whether there are genetic factors, in the hope that it can begin the work of developing a diagnostic test for ME.

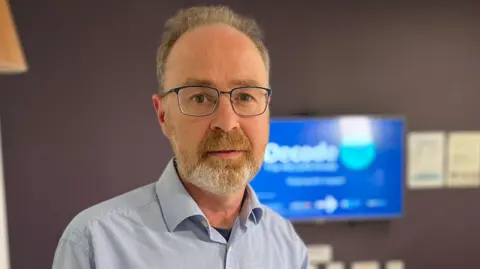

Prof Chris Ponting, who leads the study, says research into the condition is a decade behind other diseases due to a lack of funding.

“It’s a terrible disease, it’s devastating for everyone who has it – we’re talking a quarter of a million people in the UK,” he said.

Prof Ponting says he hopes the first results of the DecodeME study will be published within the next six months

“We’re wanting to find what are the root causes of ME,” he says.

“There will be many, we’re not saying that there will be one.

“Now, that isn’t going to tell people immediately what is going wrong for each and every one but it will tell us what to study.

“Should we be studying the mitochondria and pouring all our resources in to the powerhouse of the cell?

“Should we be looking at the nervous system more? Should we be focusing our attention on the immune system?”

Limited support

Patient organisations and charities say the lack of understanding of the disease is reflected in poor support services across the UK.

Action for ME have also been involved in the DecodeME study.

Chief executive Sonya Chowdhury says services in Scotland are particularly poor, with very limited support available.

“ME, whether it is mild or severe, significantly impacts on your life,” she says.

“It takes away a lot of the things of the things people take for granted.”

Last week an inquest began in Devon into the death of Maeve Boothby-O’Neill who had severe ME.

The 27-year-old died after being discharged from hospital in Exeter in 2021.

Her mother said the NHS had no way to treat the condition.

A recent legal hearing into her death heard there was a gap in NHS services for severely ill ME patients.

Her family hopes that an inquest into her death, may change the way ME sufferers are treated by the medical profession

In one of her final messages, Edina made a plea for others left struggling.

She said: “There are a lot of people like me, they don’t get seen, they don’t get heard because they can’t.

“They are stuck at home, often in their bedroom.

“There is no help but there should be.”

A Scottish government spokesman said that severe ME/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) can be debilitating and people should have access to the care and support they need to manage their condition.

“The latest NICE guidance includes clear and specific recommendations regarding the care of people with severe ME/CFS,” he said.

“Service provision is the responsibility of NHS boards and we expect all boards to provide care that is person-centred, effective and safe.

“We are currently updating health board data on ME/CFS care in Scotland with the aim of identifying areas where there is potential to progress service development.”