BBC

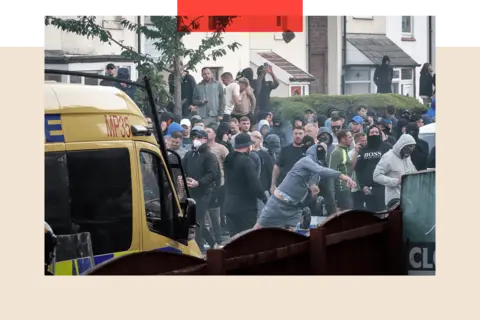

BBC“This could have been so much worse,” a Downing Street adviser tells me. “People were trying to set fire to a hotel with people inside.”

But the prime minister, they insist, is “focused” – and after a career spent largely in the criminal justice system “knows which levers to pull”.

Sir Keir Starmer was the chief prosecutor of England and Wales during the last major outbreak of civil unrest in the UK in 2011, overseeing the prosecution of thousands of people involved in five days of rioting.

Rapid and well-publicised action by the courts was key in bringing the unrest to an end, he said then. And this time ministers have emphasised “strong policing and swift prosecutions” to deter others joining the violence.

How best to get that message across to the public has been a regular discussion at emergency COBR (Cabinet Office Briefing Room) meetings.

Just as government scientists were front and centre in the pandemic, police chiefs and prosecutors have been wheeled out to land core messages with authority in this crisis.

Stephen Parkinson, the otherwise low-profile Director of Public Prosecutions, was put before the cameras. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley made regular appearances.

Yet the prime minister and his aides have pointedly avoided answering questions about the underlying causes of the riots.

I’m told the reason for this message discipline is a concern that discussing causes might be misinterpreted as suggesting some of the unrest was justified.

What happens, though, when the violence stops, the guilty rioters have been sentenced and the COBR meetings are over?

“We are starting work on the longer term challenges,” sources say.

Tackling these challenges – even deciding what they are – is set to be a crucial test for the new government, with consequences stretching far beyond the communities affected by this week’s disorder.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPossible policy changes

As police cars were burning in the UK, the Chancellor Rachel Reeves was in the US trying to burnish the government’s reputation and encourage investment.

On Monday, she insisted the TV images of far-right mobs clashing with police would not damage the UK’s international reputation as a “safe haven for investment”, dismissing the protests as “thuggery”.

But the optics could hardly have been worse for a politician trying to project stability and order under a newly-elected government with a huge majority.

It is likely the towns and cities affected in the riots will receive government money to smooth their recoveries. Local community cohesion projects have also been mooted.

But money is tight. The challenging economic outlook and the chancellor’s reputation for fiscal discipline may be reasons why government sources tell me an expensive public inquiry is unlikely.

After the 1981 Brixton riots, Lord Scarman led one. But David Cameron and Nick Clegg resisted doing likewise after the unrest in 2011. They instead commissioned a cross-party panel to learn lessons.

The role of social media will be the subject of a Whitehall review, with ministers conceding that only nine months after the Online Safety Act became law, it already needs updating and strengthening.

Yvette Cooper’s Home Office will be tasked with many of the longer-term policy challenges highlighted by the events of the past week.

Proscribing extreme right wing organisations has been discussed, but groups like the English Defence League (EDL) haven’t formally existed for almost a decade.

Instead social media has transformed the extremism ecosystem into amorphous communities which are harder to police, but which can reach hundreds of thousands more people.

For now the government has avoided discussing immigration, again for fear of suggesting any of the unrest was justified.

But in time they are likely to remind voters that the prime minister believes many people do have legitimate concerns about legal and illegal migration.

Gradually reducing the use of hotels to house migrants remains this government’s policy. But it was the last government’s policy too – with little success.

Pressure from inside Labour

With parliament in recess and many Conservatives focussed on their own leadership campaigns, much of the pressure over policy responses has come from within Labour, including interventions from London mayor Sadiq Khan and ex-shadow cabinet minister Thangam Debbonaire.

Some in the Labour Party want their leader to call out racism as a major factor. Others diagnose poverty and a lack of opportunity as a root cause.

Mental health and addiction are repeatedly mentioned in mitigation in courtrooms this week, but others were drunk or carried by the moment.

Men in their fifties and sixties have appeared before judges, as well as 13- and 14-year-old boys.

Most of the towns and cities affected in recent days have high levels of deprivation and above average levels of asylum seeker housing, according to analysis of Home Office statistics.

Regional inequality has hardly changed over decades, according to a report this week from the Resolution Foundation.

“Poor places are tending to remain poor and rich places remain rich,” its author Charlie McCurdy told me.

“The one place that has made progress on regional equality is Germany. But that’s taken three decades and spending the equivalent of the UK’s furlough scheme each year.”

Rachel Reeves seems unlikely to copy Germany’s example, but recent events may reignite the debate over scrapping the two-child benefit cap.

Poverty campaigners argue it could be one of the quickest ways to alleviate inequality.

Focus on local campaigning

One low-budget proposal is for the party to use some of its bumper crop of 404 MPs to become community champions and heavily engage with their constituents.

The inspiration is Margaret Hodge’s local campaigning to battle the far-right, anti-immigrant BNP in Barking, East London, between 2006 and 2010.

The election of 12 BNP councillors in 2006 sent shockwaves through the local political establishment, sparking a change of approach from the council and the area’s Labour MPs.

“Immigration and housing were the big two issues back then,” Mrs Hodge says, as she recounts her tactics of organising local meetings, listening to local concerns and trying to solve constituents’ problems.

“Everything I did was about reconnecting with voters to build trust. The American senator Tip O’Neill said ‘all politics is local’ and that is the lesson I learnt.”

It was an effort in which Morgan McSweeney, now Sir Keir’s election mastermind and strategy director, played a part as a young community campaigner.

Allies say Mr McSweeney is convinced MPs in areas affected by unrest must focus their time on engaging and listening.

Some argue the approach of Mr McSweeney’s mentor – the Labour thinker and former Dagenham MP Jon Cruddas – may also be deployed. He has long warned against the party becoming too metropolitan and middle class, and drifting from its working-class roots.

The violence and looting of the past 10 days has led the prime minister to postpone his summer family holiday.

Instead he will spend next week working between the buzz of Downing Street and the peace of Chequers, the prime minister’s official country residence in Buckinghamshire.

Swift criminal justice may have quelled the immediate threat of violence. But Sir Keir knows that he’ll be judged on tackling the root causes.

Top picture credit: Getty images

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.