Afterwards

Battles produce corpses, multitudes of them. In a mass killing such as the Battle of Hastings, almost 1,000 years ago, hosts of living humans were transformed into corpses, bodies were strewn across mud and grass. The rituals of treating the dead 1,000 years ago are not entirely known to us, but certainly, if we have to, we can visualise shapeless body parts scattered over the fields. Hacked-off legs and arms, a chunk of flesh torn from the loins, the cleaved-open skull of a soldier or disembodied guts above which dance a murder of crows with their dagger beaks.

Some body parts might have been identified right after the massacre. For example, a half finger that might have belonged to King Harold, or an ear from one of Harold’s brothers. All lifeless, bloody, smeared with the black soil of East Sussex. A layer of acidic earth enveloped those bones and those strips of skin, still slightly warm after being torn from their hosts. But soon these membranes, the soft and hard tissues, lost their integrity in the cold rain. Rats would have run around in ecstasy feasting on the fragmented flesh. Cats, foxes, weasels, boars, squirrels, worms, birds. It must have taken some time for the birds to figure out how they should proceed with the human remains. Were they aware that there was no need for them to fight for their prey, at least not for some weeks or months?

These days the field of the battle is serene and seemingly untouched by ancient agonies. It slopes gently down from the old abbey that was constructed on the top of the hill years after the slaughter. At the bottom of the hill are villages and farmland that lead to the sea. There is a desolation here, even though it is bathed in soft light and green hues. This desolation probably has little to do with its tortured history. When we find a place to be desolate, sad or abandoned, is it the place itself or are we projecting our inner state? Or can we really separate the two?

Relocation

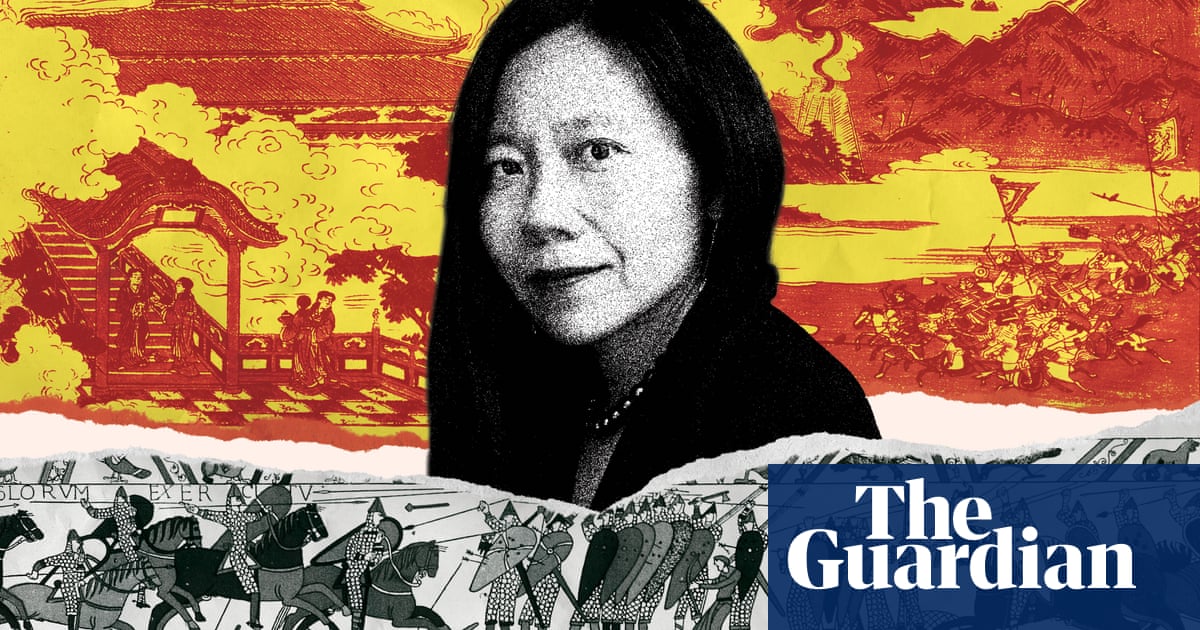

I am an immigrant. I am an artist and a woman. Being a woman does not entirely define me, being an artist describes more my way of living. It is true that I see myself as a writer and a film-maker first. I am old enough to say this, with a certain clarity in my mind. Since I left China, I have wanted to live life fully. I have wanted to explore, geographically and spiritually.

I became a British citizen some years ago, before Britain left the European Union. I had been living in London in my partner’s flat, which he owns. I never had my own place, and I didn’t mind. Having left China, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to settle in England. This changed when my parents died of cancer, first my father, then my mother a year later. I gave birth to my own child during that time and briefly went back to China with my newborn baby.

My brother and I managed to sell the family house where we grew up. I would inherit half of the money, and when I returned to England, I thought, finally, I could have a place of my own. Once uprooted, now I could root myself again. I thought about growing up by the East China Sea, and how we watched the waves every day on the littered beach. I decided to get a place by the sea, along the Channel.

A few weeks later, I called my brother in China to tell him I had found a place – in a town called Hastings. He had never heard of it. But he promised he would send me my half of the money from the sale of the family house.

A foreigner

The past is a foreign country. This is true for me. But the past of Hastings and Anglo-Saxon history is doubly foreign.

For a non-westerner like myself, to grasp the meaning of “Anglo-Saxon” is as demanding as to understand the word “Norman”. And to know what Norman means, I have to be very patient, because I have to return to the age of Norse, the Vikings, the Celts, or to times and places even more remote than the remote culture where I am from. It’s much easier for me to connect to the Mongols, the nomadic Asian people who conquered China in the 13th century. When I think of the Mongols I think of eagles, horses, Kublai Khan and ravaged cities. The gene pool of the Mongols is also where my people come from. But Norse and Vikings, those ice-capped lands and fur-covered people, would take me much longer to connect to.

I am exhausted by elaborate narratives. I want to be connected to history directly, in a simple way. If I cannot, then I should just read myths. Hunters and crows, shipwrecks and the homecoming of heroes. How many myths can one read in one’s life? Five hundred? Five thousand? The number of historical dramas we have watched and read in our lifetime is shockingly large, yet still people do not understand history. Though for some people, a very special kind of person, to know one myth (one myth entirely) is sufficient. All they need is a copy of the Bible, or a translation of the Qur’an. Or a volume of the Diamond Sutra. But not all three. The illiterate just have to listen. But for the ones who can neither read nor listen, they just have to live in their dark world. Perhaps there are large numbers of people living in that dark world. I am one of them, I read only some parts of the Diamond Sutra, and I did it half heartedly.

Here, under the hills of Sussex, or away from the beaches of Kent, if you go a little bit inland, you see people living in that dim, dark world. Not entirely dark, but dark. Men and women are trapped in narrow Victorian houses, their heating switched off to reduce the gas bill. The locals or semi-locals drag themselves along the treeless streets, a shopping bag in hand. On a street corner littered with rubbish, a gaunt-looking man passes a little plastic sachet of drugs to another gaunt-looking man. Two youthful girls in tight dresses stroll past, giggling and chatting, a beer can in hand. The girls make me feel better, and gentler, even though God knows where they are heading after finishing their beers. And I can smell winter jasmine. Somewhere behind walls or fences, the jasmines are flowering and will bloom until spring arrives. I love winter jasmine. I love their star-shaped petals, yellow and white. They remind me of China and my childhood. There were always winter jasmines growing at the school campus and in every residential street. We would pick the flowers and decorate our hair before going to the cinema or attending a large family dinner. They also remind me that I have been banished, far from the world I come from.

In China, if you look at the west of the globe, the end of the map is Britain, and that is how the Chinese visualise Britain in their mind’s eye. But I cannot complain about being in Britain, since many people still try to get to this land regardless of its fading power. It is pathetic to complain. We are being blown into this world, like a jasmine seed in the wind. We drift and then we land somewhere, we try to grow in its soil. Winter comes, spring awaits. We either germinate or turn into dust.

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

I am only at the beginning of my copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and am nowhere near the Battle of Hastings yet. Commissioned by Alfred the Great more than 1,000 years ago, it is still a very interesting book to read. It is not quite a book, but an endless record of events, some maddeningly savage, others quite trivial. Before coming to Britain, I did not know such a chronicle existed. I lived in China for most of my life. Back home I had to study similar chronicles, regardless of how tedious this was for a teenager who wanted to escape history. We had to memorise all the kings and their deeds during the Warring dynasty or the names of the lords from the Song dynasty. We had to write our lengthy homework under feeble light while our parents returned home late from their work. That was a long time ago. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is important, if you are interested at all in history. It gives us some vital facts about who did what when, but also gives us insight into how people then thought of their own history. The chroniclers were diligent and devoted monks who lived in cavernous monasteries. They wrote down the vital events with, I suppose, their slightly arthritic hands gripping goose-feather pens. A page from the early part of the chronicle reads:

Sixty winters ere that Christ was born, Caius Julius, emperor of the Romans, with eighty ships sought Britain. There he was first beaten in a dreadful fight, and lost a great part of his army.

The chronicle goes on to describe Julius Caesar moving south to Gaul, where he gathered 600 ships and returned to Britain, only to be defeated again. This account gives us a feeling that Julius Caesar’s famous “I came, I saw, I conquered” is a mere bluff. A shambolic invasion without much gain.

Tesco

Reading the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a curious experience. I like the style of “this year someone did that and this year someone else did that”. Neither scholarly nor contrived. But the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is not quite a narrative, nor is the prose designed to be beautiful. Whatever beauty we find in the prose is the accidental effect of age, or history. Its voices resemble those of journalists at the front, reporting on the progress of a war and its casualties, no time to mess about. Still, I find it incredible to read a paragraph like this:

AD560. This year Ceawlin undertook the government of the West-Saxons; and Ella, on the death of Ida, that of the Northumbrians; each of whom reigned thirty winters. Ella was the son of Iff, Iff of Usfrey, Usfrey of Wilgis, Wilgis of Westerfalcon, Westerfalcon of Seafowl, Seafowl of Sebbald, Sebbald of Sigeat, Sigeat of Swaddy, Swaddy of Seagirt, Seagar of Waddy, Waddy of Woden, Woden of Frithowulf.

Such a rapid pace, such a busy listing! Yet what comes from the writing hand of these few monks is History, even if it can only be challenged by very sceptical minds.

Names and places, such as West-Saxons are still relevant to current England. For some reason, I am fascinated by such names: Essex, Sussex, Middlesex (now a historic county) and Wessex (which ceased to exist in 1066). The sounds are very exotic to Chinese ears. Once I visited a town in Suffolk called Saxmundham, and I could not get over its ancient name. Saxmundham means Saxon-world-village. Very grand indeed, even though the town was very small. I wandered its plain streets, trying to discover an ancient relic that might capture my attention. Eventually, after hours of wandering, I was so weary I entered the large Tesco to replenish my energy.

Saxons/Tang

The trees are still leafless, though their green buds are trying to open in the cold. Only the blackberry and gooseberry bushes send out their thorny shoots on the roadsides. April is definitely the cruellest month in Britain. TS Eliot nailed it after living in England for several years as an American. Perhaps a foreigner knows more about his adopted land than the locals, because a foreigner feels more acutely the particularities of a new environment.

I have never adapted to English weather, at least not so far. As the gloomy days of March passed in snowflakes and frost, I imagined the weather would improve soon, that I would be able to survive in my cold Hastings flat. But April has arrived, and it is even colder. In the flat I wear a padded coat and wool trousers and woolly slippers. I read the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to pass the time. I hope to understand the year 1066, and the events around that period, which, I am told, shaped England to this day. I don’t think many of the locals care much about the remote past of Hastings and the surrounding areas. But I cannot be so complacent. I don’t like to think of myself as a selfish and indifferent immigrant, even though I can be selfish and indifferent in many other ways. It’s simply that I wouldn’t feel good about owning a home in a foreign town without understanding its past, even though that past is so distant it may as well be a myth, a hyperbolic narrative belonging only in some expensive production from Netflix.

So I turn my attention to that period. In China, if we want to mention a high cultural point of history, we say: “It’s like the Tang dynasty.” Mostly, this would be said with a sigh by old people: “It will never be as good as in the days of Tang, when the country was wealthy and people were content …” Tang culture was more than 1,000 years ago, and it ended around AD900, before the Battle of Hastings. A god in the heavens would get a good picture of that time by looking to the east and then looking to the west. He would see that during the landscape-painting and flower-worshipping Tang period, the old Saxons were still the dominant power in England, though England was not yet a concept. Vikings and Normans were not yet in charge. I wonder if the locals said the same thing after the Norman conquest: “It is not as good as in old Saxon days,” they might have said bitterly, thinking of their family, slaughtered by the Normans. “The old kingdom of Wessex has gone.” Perhaps the Anglo-Saxons sighed sorrowfully, just like old Chinese people.

But even during those good old days, killing was everywhere and everyday. Violence was the reality of life. I, too, come from a history of violence, probably an even more extreme one. In the eighth century, the An Lushan rebellion killed 36 million people in China, one-sixth of the world population at the time. Killing occurred by hand in ancient times, slaughtering one by one – it takes a huge amount of energy and effort. To slaughter 1 million would be an immense task, let alone 36 million.

I open a page in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, around the same period as the Tang dynasty in China:

AD780. This year a battle was fought between the Old-Saxons and the Franks; and the high-sheriffs of Northumbria committed to the flames …

AD784. This year Cyneard slew King Cynewulf, and was slain himself, and eighty-four men with him …

AD789. This year Elwald, king of the Northumbrians, was slain by Siga …

AD792. This year Offa, King of Mercia, commanded that King Ethelbert should be beheaded; and Osred, who had been king of the Northumbrians, returning home after his exile, was apprehended and slain …

The relentlessly violent, almost apocalyptic nature of the period dominates many parts of the chronicle. It is such a contrast to our life now, at least for people living in peacetime. The more one reads about history, the more one questions the nature of peace. A great danger seems to lurk behind times of peace, as though the great fire can be ignited from a tiny local eruption in the middle of night.

Normans

For the English, on one side of the Channel, the Normans were the enemy. But the Duke of Normandy was a family member of the English king. Cousins. Brothers. Feuds and enmities. Always the same. Europe is a closely knit family. Wasn’t the last tsar of Russia the cousin of the last kaiser of Germany as well as of King George V of England? Always the same. Power remains within the family, even though everyone tries to get rid of the ones stepping on their toes. Still, here we are talking about 1,000 years ago. Mad Europe, raging wars and the awful tribalism that humans are so good at engaging in.

The Normans were from Normandy and beyond. “Who are the Normans?” I imagine a student asking her teacher in class. “The Normans,” the teacher answers, “are also called Norsemen or Northmen. They are a loose collection of northern Germanic groups.”

When we think of Vikings, the cliche from the movies comes to mind: a violent sea people, sailing forth in interesting looking boats to plunder food and goods from agricultural lands far from their home. Yet everyone seems to be linked to Vikings. William the Conqueror was a descendant of Rollo, the Viking who founded Normandy. On the other side of the Channel, Harold Godwinson’s mother, Gytha, was Danish, related by marriage to King Cnut, the ruler of the North Sea empire. I have a sense that much literature has been written about the Vikings, all charged with pride and myth, but not so much about the Normans. My understanding is that we are fascinated with the more violent group who managed to conquer the less violent group.

Anglo-Normans. That’s a good word, a useful word. It suggests the composite nature of one of the populations around this part of the coast in olden times. Of course, I never hear anyone use it now, in our day-to-day life. Our DNA has demonstrated all possible inceptions for our people. We can have one and many origins at the same time. Even for a villager like me, born in a totally enclosed Chinese peasant place, I, too, am a mix of bloods and genes. I am of mixed race. My father’s family was Hakka Hui, of Muslim origin, and my mother’s family was Han Chinese. I am a daughter of the Confucian tradition with a communist upbringing. I speak Hakka and Mandarin, as well as European languages. I share many things with everyone in this world. But apparently, we humans also share 60% of our DNA with a banana. How arbitrary is that? Half of our genes have counterparts in bananas! We are just a bunch of very complicated and violent bananas. Neither Vikings nor Anglo-Normans can escape their relation to bananas, even if the Vikings probably never tasted or saw a banana in their time.

Burning wild fens

For someone like me, growing up under the heavy censorship of the communist regime, I cannot help but have more faith in the ancient records than the modern ones. Perhaps that is why in a second-hand bookshop in St Leonards I opened a random page of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and was struck by what I read of how the Vikings raided England:

For three months they plundered and burned, and then proceeded further into the wild fens. And they burned Thetford and Cambridge and then went southward to the Thames and those who were mounted rode towards the ships and then turned westward toward Oxfordshire and thence to Buckinghamshire and so along the Ouse until they came to Bedford and so forth to Temsford and burned everything where they went. Then they went to their ships with their plunder.

The text, with its straightforward tone, was somehow mesmerising to me. As I walked home with the book under my arm, I could not help but think of the “burning wild fens”. Fens – an unfamiliar word for me, not ferns. I checked its origin. It is Germanic, related to Dutch veen and German Fenn. I read those mysterious lines again: “For three months they plundered and burned, and then proceeded further into the wild fens. And they burned Thetford and Cambridge and then went southward to the Thames …” A series of powerful images were forming in my head as I walked past the grey shore.

Burning wild fens. I could not get these words out of my head.

Incredible. But in my experience Britain is always inked with deep green and splashed with rains, burning the land would be difficult. And it was probably even wetter and colder 1,000 years ago when Vikings raided the isles. In the wetland of Britain, wild ferns, not fens, would grow lushly everywhere. So strong were their stems, they must have been hard to get rid of, even if the Vikings were endlessly burning the land. Wheatfields and orchards might not have survived after months plundering. Or, perhaps, one summer afternoon 1,000 years ago, the sky was blue and the sun hot. Ferns, nettles, barley, corn, wheat, beets, fruit trees on English hills might be set alight, like being caught in a desert fire. They could burn from the Kent coast to Norfolk, or from Blackpool to Yorkshire. All of them were being torched by the brutes.

But 1,000 years have passed now, most of those brutes have become very civilised. They have become tree lovers and land conservationists. It is only a matter of time, though a matter of a long, long time.

The strait of Dover

The strait of Dover, especially at the Channel’s eastern end, is the narrowest point between Britain and France. In French, this part is called Pas de Calais. Because it is narrow, it has gathered more sediment on the seabed than other parts of the Channel. The water is relatively shallow, with the average depth about 35 to 55 metres, whereas the average in the rest of the Channel is 63 metres.

But still, this is the North Sea coast, part of the Atlantic. Everywhere along this coastline shares a similarly harsh seascape: rugged and eroded land, salt marsh and low-lying vegetation. Standing at the top of any hill in Hastings or Bexhill or Brighton, you can feel that harshness, even on a mild sunny day.

I recently read a report published by some geologists that said the seascape in this part of the world is recognisably similar to the seascape from 1,000 years ago. That’s remarkable. I can almost picture the vivid seascape during the Battle of Hastings by looking at the current one.

One of the local papers, the Hastings Independent, reports that there were migrant boats yesterday carrying 1,500 refugees trying to cross the Channel. Did they arrive at Dover? The news doesn’t say. What it does say clearly is that the Border Force were authorised to turn the boats back to the French side. So, does it mean 1,500 people have been turned back into the Channel? Or is that confidential information, which won’t be revealed to the public? I have learned that once migrants land on English soil (after being received by the police) they can claim asylum status in the UK. So the government clearly wants to turn back the boats to French waters. But everyone in Britain knows there has been a shortage of migrant workers in the country. There are not enough truck drivers, not enough fruit pickers, not enough builders, and not enough nurses and doctors.

I listen to more news on the radio. There is a dispute about the behaviour of the British Border Force. When they turn back the migrant boats towards French water, they need the consent of the French to do so. Apparently the French have already refused this plan and are simply not engaging with them. So, everyone wonders, what will happen with the boats and the refugees? How long can a boat remain in international waters? Until everyone is drowned? And only at the drowning point will there be an official “rescue” by police on one side or the other?

I think of Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold. The final lines sum up my feeling about the immigrants on the boats during the night, before they become the morning news on the radio and in the paper:

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

The beach is one of the first battlegrounds. In my Chinese village of Shitang by the Taiwan strait, mainlanders would leave secretly on their boats at night in order to get to Taiwan, a supposedly free land on the other side of the water, only to be shot at by soldiers when they reached international waters. As a child I heard of so many villagers being shot right on their boats. But some succeeded.

The beaches of Shitang were also a place of mourning for our village widows. Those wives never saw but always watched for their husbands returning – some died from the storms, some from reasons never known. I know my childhood beaches. And I know my childhood sea.

Yet as I walk on these shingle stones, I see nothing, hear nothing. Only the wind, the waves, the unbearable forgetfulness of history.

Extracted from My Battle of Hastings, published by Chatto & Windus