Getty Images

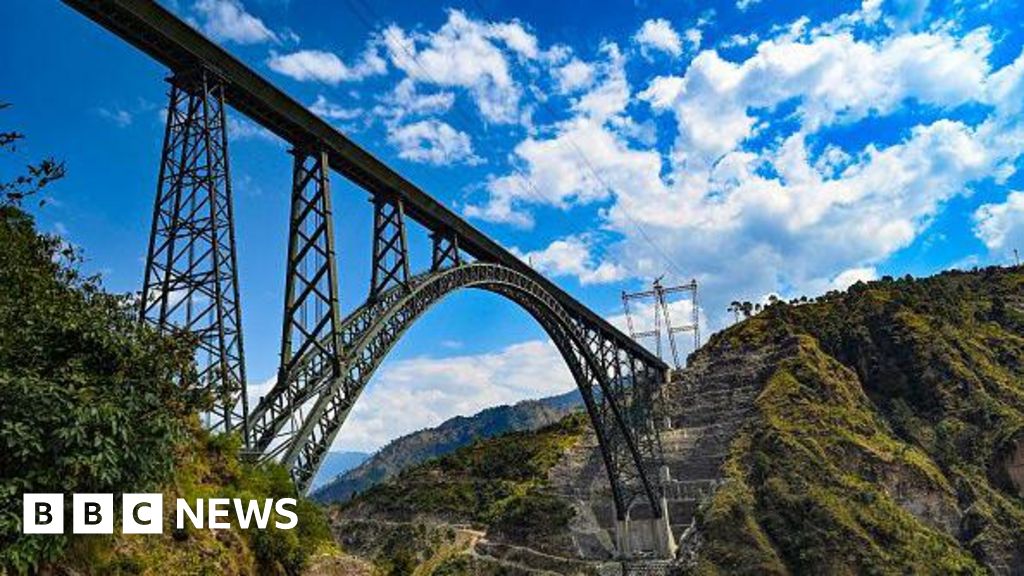

Getty ImagesThe world’s highest single-arch rail bridge is set to connect Indian-administered Kashmir with the rest of the country by train for the first time.

It took more than 20 years for the Indian railways to finish the bridge over the River Chenab in the Reasi district of Jammu.

The showpiece infrastructure project is 35m taller than the Eiffel Tower and the first train on the bridge is set to run soon between Bakkal and Kauri areas.

The bridge is part of a 272km (169 miles) all-weather railway line that will pass through Jammu, ultimately going all the way to the Kashmir valley (there is no definite timeline yet for the completion). Currently, the road link to Kashmir valley is often cut off during winter months when heavy snowfall leads to blockages on the highway from Jammu.

Experts say the new railway line will give India a strategic advantage along the troubled border region.

The Himalayan region of Kashmir has been a flashpoint between India and Pakistan for decades. The nuclear-armed neighbours have fought two wars over it since independence in 1947. Both claim Kashmir in full but control only parts of it.

An armed insurgency against Delhi’s rule in the Indian-administered region since 1989 has claimed thousands of lives and there is heavy military presence in the area.

Afcons

Afcons“The rail bridge will permit the transport of military personnel and equipment around the year to the border areas,” said Giridhar Rajagopalan, deputy managing director of Afcons Infrastructure, the contractor for the Indian railways that constructed the bridge.

This will help India exploit a “strategic goal of managing any adventurism by Pakistan and China [with whom it shares tense relations] on the western and northern borders”, said Shruti Pandalai, a strategic affairs expert.

On the ground, sentiment about the project is more nuanced. Some locals, who did not want to be named, said the move would definitely help improve transport links, which would benefit them. But they also worry it would be a way for the Indian government to exert more control over the valley.

The railway line is part of a larger infrastructural expansion – along with more than 50 other highway, railway and power projects – by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, which stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status and divided the state into two federally administered territories in 2019.

The controversial move was accompanied by a months-long security clampdown which sparked massive anger in the region. Since then, the government has brought in several administrative changes that are seen as attempts to integrate Kashmir more closely with the rest of India.

Ms Pandalai adds that while India’s plans for the region would naturally be guided by its “strategic aims”, it also needs to take “local needs and context” into account.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe construction of the Chenab bridge was approved in 2003, but faced delays and missed deadlines because of the region’s treacherous topography, safety concerns and court cases.

Engineers working on the project had to reach the remote location on foot or by mule during the early stages of construction.

The Himalayas are a young mountain range and their geo-technical features have still not been fully understood. The bridge is located in a highly seismic zone and the Indian railways had to carry out extensive exploration studies, modifying its shape and arches to ensure the bridge could withstand simulated wind speeds of up to 266km/h.

“Logistics was another major challenge given the inaccessibility of the location and the narrow roads. Many of the components of the bridge were built and fabricated on site,” said Mr Rajagopalan.

Besides the engineering complications, the railways had to design a blast-proof structure. Afcons claims the bridge can withstand a strong “explosion of up to 40kg of TNT” and trains would continue to ply, albeit at slower speeds, even if there was damage or a pillar was knocked out.

Experts say that enabling all-weather connectivity to the Kashmir valley could give the region’s economy a much-needed boost.

Poor connectivity during winter months has been a major bugbear for the valley’s largely farm-dependent businesses.

Seven in 10 Kashmiris live off perishable fruit cultivation, according to think-tank Observer Research Foundation.

Ubair Shah, who owns one of Kashmir’s largest cold storage facilities in Pulwama district in south Kashmir, said the impact of the rail link could be “huge”.

Right now, most of the plums and apples stored in his facility make their way to markets in northern states like Haryana, Punjab and Delhi. The new railway line would give farmers access to southern India which could eventually help increase their incomes, he said.

Yet without better last-mile connectivity, he doesn’t expect a quick shift to railway cargo.

“The nearest station is 50km away. We’ll have to first send the produce to the station, then unload it and load it onto the train again. It’s too much handling. With perishables you have to try and minimise that,” Mr Shah said.

The project is also expected to boost the region’s tourism revenue.

Kashmir’s spectacular tourist spots have seen a recent surge in arrivals despite the remoteness of the region. A direct train between Jammu and Kashmir’s Srinagar would not only be cheaper, but also halve travel time, which could give tourism a further shot in the arm.

There will be several challenges too.

Kashmir continues to be dogged by incidents of violence. A recent spurt in militant activity – which seems to have shifted from the Kashmir valley to the relatively calmer Jammu region – is a particular cause for concern.

In June, nine Hindu pilgrims were killed and dozens injured after militants opened fire on a bus in Reasi – where the bridge is located – in one of the deadliest militant attacks in recent years. There have been several other attacks on the army and civilians.

Experts say such incidents are a reminder of the fragility of peace here – and without stability, connectivity projects would go only so far in reviving the region’s economy.