Getty Images

Getty ImagesFinally, after five years of changing approaches to exams and grading, this is it.

This is the year that A-level grades across England, Wales and Northern Ireland are back, more or less, to where they were before Covid.

Most students getting level three results were in Year 9 when the pandemic started.

They were the first year group to sit in-person GCSEs after Covid lockdowns, when they had some extra measures to help them out, like advance information about topics to revise.

This year, though, that extra help was gone, and the approach to grading was the same as it would have been if exams had never been cancelled in the first place.

Here is what you need to know.

1. Top grades rise overall

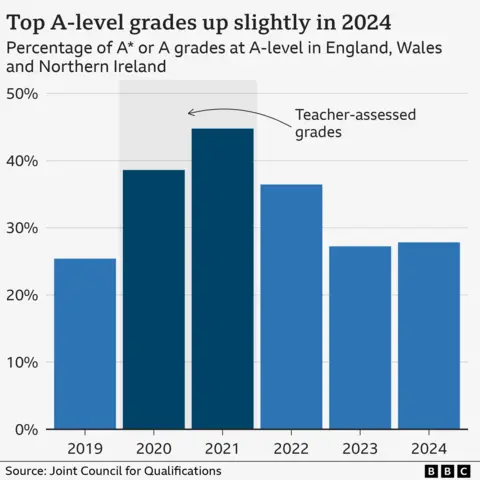

Across the whole of England, Wales and Northern Ireland, top grades have risen for the first time since 2021 – with 27.8% of all grades marked at A* or A.

That is up from 27.2% last year.

Individual nations’ results tell a more complicated story, though, with top results up in England, but down in Wales and Northern Ireland.

This year the proportion of A-levels marked at A* and A was:

- 27.6% in England, up from 26.5% in 2023

- 29.9% in Wales, down from 34%

- 30.3% in Northern Ireland, down from 37.5%

Some students in Wales and Northern Ireland may feel disappointed, but the story here is bigger than one of individual performance.

There has been an effort to bring top grades back down in line with pre-pandemic levels over recent years, ever since sharp rises in 2020 and 2021 when exams were cancelled and results were based on teachers’ assessments.

In England, the exams regulator aimed for that return to 2019 levels to happen last year (although they remained slightly higher).

But in Wales and Northern Ireland, it was always the plan that this year would be the moment grades fell back in line with pre-Covid levels.

Across all three nations, the percentage of top grades this year remains higher than in 2019, when it was 25.4%.

It is worth bearing in mind that, unlike last year’s A-level students, these teenagers had experience of sitting external exams before this year, and exam results on which to base their A-level subject choices.

2. England’s north-south divide persists

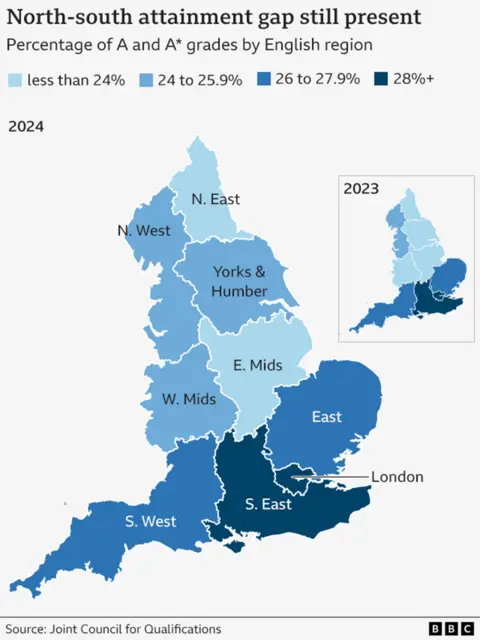

Overall, 27.6% of A-level grades in England were given an A* or an A this year.

But the proportion varies depending on where you live, and regional differences remain entrenched.

The gap between the two regions with the highest and lowest proportions of A* and A grades each year has grown, and is still higher than it was before the pandemic.

In London, the highest-performing region this year, 31.3% of all grades were marked A* or A, whereas in the East Midlands, this year’s lowest-performing region, it was 22.5%.

More broadly, we are still seeing a north-south divide – which existed before the pandemic, and got worse over Covid.

This year, though, many regions in the Midlands and the North have improved at a higher rate than those in the South. The North East and the West Midlands saw the biggest growth in top grades.

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said it was “too often the case” that where you come from determines what you can achieve.

“The gaps we’ve seen opening up under the last Conservative government when it comes to regional differences are really stark,” she said.

“There is an awful lot that we need to do.”

MPs warned last year it could take a decade for the gap between disadvantaged pupils and others to narrow to what it was before Covid.

3. Maths is a big winner

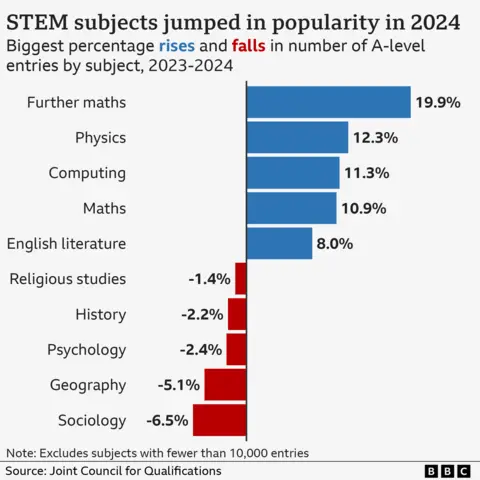

There has been no change in the top 10 most-popular subjects this year.

But maths is the real winner – not only is it still the most popular subject, it is also the first A-level to ever surpass more than 100,000 entries.

Across all subjects with more than 10,000 entries, further maths saw the biggest increase in uptake, followed by physics, computing, maths and then English literature.

(Entries to computing, by the way, have grown 83.1% since 2019.)

There is concern, though, that boys make up the majority of students in most science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) courses.

A report last week by the National Foundation for Educational Research, commissioned by the British Academy, suggested the range of subjects young people are studying after the age of 16 has narrowed.

It said there had been a particular decline in uptake of arts and humanities subjects, with 38% of sixth form students studying a humanities subject in 2021-22, compared to about 60% in 2016.

All of this will ring alarm bells for universities trying to recruit enough students to keep arts and humanities programmes open.

4. T-level dropout rate remains high

It is the third year of results for T-levels in England – the technical qualification rolled out under the Conservative government which involves splitting time between classroom learning and industry placements.

Dropout rates remain high. Last year, 66% of T-level students completed their course.

The retention rate is better this year, at 71%, but still well below that for A-levels in England, which is consistently above 90%.

It matters because T-levels are “here to stay”, according to Ms Phillipson.

“We want to make sure that T-Levels are a success,” she said.

“The last government botched the rollout and there are lots of underlying problems that we are seeking to address.”

5. Success for university applicants

It is a good year to be applying to university, with 82% of applicants getting into their first choice.

Figures from the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service suggest that 376,470 applicants – of all ages, from everywhere – were accepted into their “firm” choice – a 4% rise on last year.

More people got top A-level grades this year, but there is also a bigger backdrop here.

Universities say they need more funding. According to the Office for Students, about 40% of them in England are likely to be in deficit.

Tuition fees for domestic students have remained more or less frozen since 2012, losing their real-terms value because of inflation.

Universities have been recruiting more international students – who pay higher fees – over a number of years to make up for a loss in funding. However, recent changes to visa rules and a currency crisis in Nigeria are expected to lead to a decline in the number of international students starting at UK universities next month.

All of this means that universities need to shore up their funding – and part of that will involve recruiting more domestic students.

Additional reporting by Rob England, Phil Leake and Muskeen Liddar