A lending institution whose origin can be traced back 218 years, to 1806, could lead one to misjudge the State Bank of India (SBI) as a weighty and slow-to-adapt organisation, where ‘largest’ and ‘oldest’ are the only qualifications that could be attached to describe its banking reach. But this is far from the truth.

In the buzzing space of aggressive, competitive and innovative lending by private banks, new-age lenders and fintech companies to a technology-savvy young Indian, SBI’s relevance is intact.

SBI finds its roots from the Imperial Bank of India, which carried out all commercial banking activities as a central bank in British-ruled India till 1935, after which the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was founded to tackle economic troubles, post World War I.

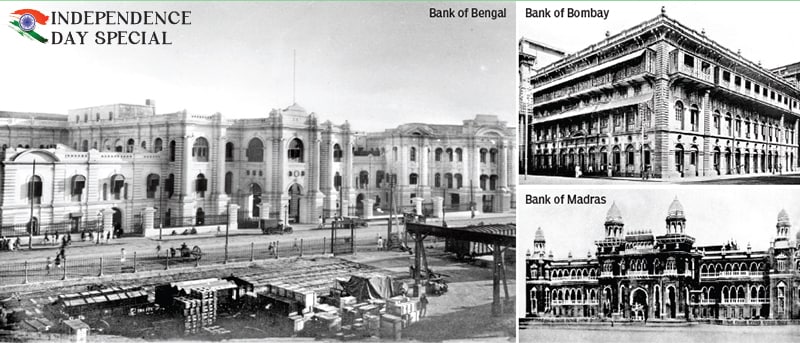

Imperial Bank of India, which was headed by two governors—British bankers Norcot Warren and Robert Aitken—was, in 1921, the result of an amalgamation of three Presidency Banks of colonial India: The Bank of Bengal, the Bank of Bombay and the Bank of Madras.

The bank operates under its own legislation—besides being governed under the Companies Act, 2013, the Banking Regulation Act of 1949/1966 and the RBI Act, 1934—which helps provide SBI with clarity on cadre, leadership, governance and even autonomy. The role of the executive committee of the central board of the bank can be seen.

Early in its establishment, the bank was mandated to establish 400 SBI branches by 1960, which helped it leapfrog into an important role of ensuring financial inclusion, rural credit and lending to small businesses and women entrepreneurs by the mid-1980s.

Rural credit, Sustained Restructuring

SBI has in recent decades has achieved a lot of firsts: When microfinance and rural credit were still off-limits for private sector banks, SBI was the first in India to recruit officers exclusively to promote microfinance. SBI, in the 1990s, adopted NABARD’s SHG-Bank Credit Linkage [self-help groups], which is part of the overall mantra of the SBI, to be the banker to every India and boost rural credit growth.

The bank has never deviated far from what it was set out to do. The purpose of the State Bank Bill placed in the Lok Sabha on April 22, 1955, was “not merely to take over” the Imperial Bank but “to recreate our rural life, to vitalise and strengthen our peasantry, and to rejuvenate our rural areas”, according to the Minister of Revenue and Defence Expenditure on the Bill, as stated in SBI’s archival book, Banker to Every India, published in 2023.

In the mid-1960s, SBI was the first bank to have a separate division for lending to small businesses and industries. A renewed push to the sector came in 1985, when, following government guidelines, SBI began to provide 40 percent of their total credit to priority sectors.

Agriculture credit saw a further jump in the 1980s, as SBI started financing farmers through primary agricultural credit societies and farmers’ service societies. By the end of 1980, the number of beneficiaries increased to 242,000 from 2,860 farmers as on June 15, 1970. Loan disbursals during the period increased to ₹22.17 crore. Loans disbursals are now at ₹32.28 lakh crore as of FY24.

In 1970, a rapidly-expanding SBI approached the Indian Institute of Management (Ahmedabad), to suggest organisation changes within itself to make it lean and trim. This led to the creation of new circles, which would be a conglomeration of regional offices to offload increasing pressure on Local Head Offices (LHOs).

In 1986-87, Ferguson, which was a part of KPMG, was approached by SBI to refresh their standard operating procedures (SOPs) —which is now called process controls and flows. Ashvin Parekh, then at Ferguson, and now an independent banking and strategic consultant, was involved with this project.

“The idea was to make banking activity a science and not an art,” Parekh says. He went to Kolkata to examine the SOPs of the Imperial Bank, all stacked in a massive warehouse. He went back to the SBI chairman (DN Ghosh) and said he was prepared to create a proposal provided the bank did it. “All the SOPs were broken up into various components and handed over to different offices. One office would update them and the other office would examine and verify them,” Parekh says.

In 1991, post-liberalisation, when the RBI decided to set out new guidelines for banking licenses—and four private banks rushed to launch their operations in the next two-three years—SBI went to McKinsey in 1993, seeking another restructuring to meet new-age challenges. This led to the creation of different banking groups called Strategic Business Units (SBUs).

Similarly, in 1998, during Parekh’s stint at PwC India, SBI approached the consultancy to revamp their Basel framework, which involved maintaining capital and governance norms for banks, as mandated by the regulator. This was perhaps the first attempt of its kind by a public sector entity.

“SBI is characterised by three things: A strong cadre, led by its structure, where you have circles, branches and opportunities for individuals to rise from within the bank. The second is autonomy, which ensures a solid integrated background within the bank. This helps to keep the bank’s DNA intact,” Parekh says.

Most public-sector banks who were primary lenders to several steel, power and infrastructure projects in the previous decades, have seen their balance sheets suffer due to these loans turning bad. SBI, like other public sector banks and even the private lenders, was no exception. It had struggled to implement and define proper policies, and there was a lack of follow-up and accountability.

Two former SBI heads, Arundhati Bhattacharya, who in 2013 became the first woman chairperson of the only Indian bank on the Fortune Global 500 list, and her successor Rajnish Kumar, battled successfully to improve asset quality at the bank. Bhattacharya, in her four-year term, altered the lending book by lowering corporate exposure to 46 percent and 51 percent retail. By the end of Kumar’s term in October 2020, the corporate and retail portfolios were both lower at around 38 percent each, while the balance involved lending to small businesses and agriculture.

The balance sheet was under severe stress owing to high level of NPAs (gross NPAs around 9.8 percent) when Kumar took charge in 2017 and the first priority was to repair it. “It was done through stepping up resolution process by re-organisation of Stressed Assets Resolution Group and aggressive provisioning for loan losses,” former SBI chairman Kumar tells Forbes India. He also focussed on strengthening the credit review department which could prevent formation of NPAs again in a big way. When Kumar’s term ended, gross NPAs had improved to 5.28 percent.

Kumar added that changing staff behaviour and attitude through Nayi Disha, an organisational intervention programme covering all employees “was a huge success.”

Prior to this, his predessor Bhattacharya had fixed some concerns which the bank was facing at that time. This included making it more cost-effective, making the bank more focussed towards improving fee income, which had become stagnant due to lack of co-operation among departments. The bank management was also taught the ‘collaboration inside and competition outside’ approach where cross-selling of financial products gained momentum under her leadership.

Shareholders’ Confidence; Digitisation

SBI’s top management has managed to walk the tightrope of being a robust, commercially viable bank, despite its size and focus on priority sector lending. It also met unwritten compulsions which it has been expected to serve.

In 2020, after consultations with the government and the RBI, SBI was brought in to bring in capital as an investor—besides other banks —to rescue private lender Yes Bank from collapsing. The RBI had in March 2020 placed Yes Bank under a month-long moratorium, to prevent a run on deposits.

Kumar was leading SBI at that time and this was probably the first instance of a large public sector bank bailing out a small private sector bank. Today, Yes Bank, in its June-ended 2024 quarter, achieved its highest quarterly profit of ₹502 crore and the balance sheet has grown around 15 percent year-on-year, since the rescue act.

SBI has been delivering returns to its shareholders and investors too. It is the seventh largest Indian company—and the highest public sector lender—by market cap at ₹7.6 trillion as of August 2, according to Bombay Stock Exchange data.

In recent years, much of the bank’s attention has been to build on its technology expansion, enhance digital banking and stay relevant, as a banker, to young Indians. “SBI has become a vibrant, modern, digitised bank,” Kumar says, under whose leadership the YONO digital app was launched.

Parekh agrees that SBI has a robust platform and business in place, through the YONO app. “But I think, because its balance sheet size continues to grow, it can certainly play an important part in the growth of the country. At the same time, it can do this without compromising on the quality of its lending base. SBI is not susceptible to this risk because of strong processes, complete transparency and good governance,” Parekh says.