In 1987, a group of white British independent label bosses came together to invent a new marketing category: world music. Eager to promote the growing public interest in artists from Bulgaria, the Middle East and across Africa, they were encouraged by the massive success of Paul Simon’s Graceland album the previous year, which had spliced his New York songcraft with the music of South African artists such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Their campaign was a massive success, and even led to the introduction of a new category at the Grammys.

But “world music” is now seen as evoking a patronising, even colonial “us and them” mindset from the west towards global majority musicians – the Guardian stopped using the term in 2019, the Grammys in 2020.

Joe Boyd was one of those at that 1987 meeting. The US record producer, who has helmed sessions with Pink Floyd, Nick Drake and dozens of globe-straddling artists, is unrepentant. “I understand the complaints, but whatever we called it would be seen as colonialist,” he says. “Just the fact that this group of white label owners were doing the naming and putting these records together in a corner of a record store so people could find them, would fit the definition of an offence.

“You can complain at the concept, but you can’t complain about the practical effect,” he adds. “All these musicians would never have had these careers, met these audiences and gotten paid. I don’t believe there was any other way it could have been done. It changed people’s lives and the music changed lives. ‘World music’ was flawed – but not for that reason.”

Now 82, Boyd was born in Boston, graduated from Harvard and became seemingly omnipresent in countercultural 60s music: he was doing the sound when Dylan went electric at Newport folk festival and after moving to London, co-founded the psychedelic, Hendrix-hosting UFO nightclub. Alongside his production work (REM were a later client) he’s also been a label boss, tour manager, film-maker and writer: in 2006 he published White Bicycles, an intriguing memoir of that 1960s scene.

Music from around the world is the subject of the long-awaited and controversial follow-up book, And the Roots of Rhythm Remain: A Journey Through Global Music. Named after a Graceland lyric, it is praised on the jacket cover by Brian Eno, Robert Plant and Ry Cooder – but it becomes clear that Boyd’s words could certainly rile fans of dancehall, electronic music or contemporary African pop.

It’s not the memoir of his later years that might have been expected (though plenty of personal stories and gossip are included) but a massive, opinionated musical history in which he charts how, thanks largely to slavery and Roma migration, “the two tides” of music from Africa and India interacted with and transformed western music.

Having produced musicians from Africa, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cuba, India and beyond, he’s well placed to examine this extraordinary story, which ends, in Boyd’s book, with the arrival of the drum machine. “I’m writing about music that has hand-made, personal, human-made rhythms,” he says, acknowledging that his resistance to digitally made music won’t be popular. “Some people will read the book and steam will come out of their ears. I make no pretence of objectivity when it comes to my own taste and the battle for what people are going to be listening to 50 years from now.”

He is speaking from Germany, where he is recording the audiobook. As the printed version is more than 900 pages and 400,000 words long, this is no small task.

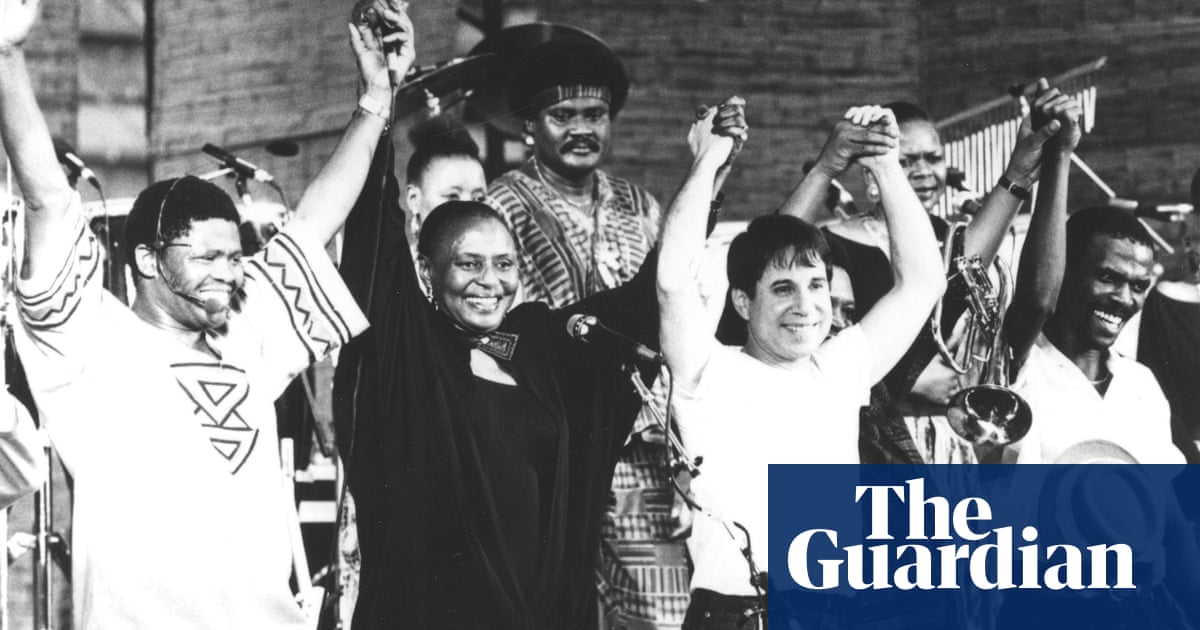

He starts with South Africa and Paul Simon, positioned as something of a hero throughout. Boyd chronicles the Graceland tour – Miriam Makeba apparently cold-shouldered Ladysmith Black Mambazo amid Xhosa-Zulu tensions – then swings back to the country’s political and musical history, with a reminder that Zulu choirs were a success in London in the 19th century, despite Charles Dickens commenting: “If we have anything to learn from these noble savages, it’s what to avoid.”

Cuba and India follow, then Boyd circles back to the year 450 and the migrations of the Roma “who transformed every musical culture they touched”. In eastern Europe, he delights at hearing the 35-part Philip Koutev National Folklore Ensemble and massively successful Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares, and he examines the repression of traditional music in the Soviet era, comparing musical protests by angry female Russian villagers to the authorities’ alarm at Pussy Riot. He chronicles the killing of Ukrainian musicians in 1938 as a sign of Soviet determination that Ukraine should not have a standalone culture. “And they are still doing it,” he says.

Elsewhere you can find the story of tango star Carlos Gardel, instructions on how to samba, or a thoughtful appreciation of Fela Kuti (with emphasis on the rhythms of Tony Allen). The chapter on Jamaican music, meanwhile, includes a comment on dancehall “sounding as if it was put together by someone with a computer and a short, coke-fuelled attention-span”. I ask him to elaborate. “The shift from real rhythm to machine rhythm has changed something about people’s relationships with music,” he replies. “I can enjoy some tracks that are machine-driven but they don’t enter my brain through the same doorway.”

He argues that Paul Simon’s use of rhythms from different cultures “for me works so much better than the other way round: ‘Let’s take this melody or song and put a mid-Atlantic dance beat under it’.” So is he saying that other cultures shouldn’t be lifting western rhythms? “Of course they can! They can do anything they like. I’m just saying that when I hear fusions – whether from the west or the global south – I find it less interesting. Simon did the opposite and sells millions of records.”

Which takes us back to the controversy over “world music”. (I wasn’t actually at the meeting where it was invented, as he states in the book, but I did bring together many of those who were there for a Guardian discussion, years later.) The problem with how “world music” success developed in the late 1980s onwards, Boyd argues, is that “it started with great artists from local cultures who had become popular in their culture – and we loved them. Crowds here in London poured out to hear African artists who were still big stars in their home territories. But eventually, once the drum machine hit, there were fewer of those artists around”.

Western fans loved traditional work that, heard in their own countries, had the shock of the new – such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Bulgarian choirs or Buena Vista Social Club – but this music was considered dated back home.

He tells the story of Virgínia Rodrigues, a Brazilian “chamber samba” singer brought to his attention by her compatriot Caetano Veloso. She became a cult success in the west and Bill Clinton bought 100 copies of her album Sol Negro, but back in Brazil “nobody picked up on it. Before she could capitalise on all the great publicity, she got disillusioned and the relationship fell apart”.

But, he adds, “one of the many points of this book is to put ‘world music’ – the whole thing that happened in the 80s – in a historical context. It’s a blip. A pinprick. Nothing in the 80s or 90s compares with Latin dancing in New York in the 40s, or the impact of bossa nova in the early 60s.” What about reggae and Bob Marley? “His impact when he was alive was huge but in the 80s and 90s it was more nostalgic.”

What then of current situation, now that music of all varieties is available to everyone across the globe through the internet, allowing hip-hop or electronica to inform traditional music? “My book is not about the current scene,” he says, “and I had to stop somewhere”. So he doesn’t include now-established bands such as South Africa’s BCUC, or South Korean traditional-electronica fusion exponents such as Jambinai. As for bestselling African pop artists such as Burna Boy (one contemporary musician who does get a mention), he agrees they “won an audience that Fela never managed … but the vibe is hard-edged and electronic-modern, while the singing is filled with the sort of Auto-Tuned grace notes that dominate modern international vocal performance”.

He admits his opinions are passé, and that he’s been left behind. “One of music’s jobs is to be a bludgeon for the younger generation to hit the older generation over the head with – and the younger generation have succeeded with me.” But he’s not totally despondent. “Young people make stuff I don’t want to listen to,” he says, but adds that they also love steel bands, the New Orleans second-line tradition or Brazilian axé. “That’s the dream!”