One hundred years ago, if you were a white middle-class housewife living in Iowa’s gold-domed capital city, you were probably a member of the Des Moines Women’s Club.

It was founded in 1885 by a group that included Calista Halsey Patchin, the first female reporter at the Washington Post, as part of a national movement to help women seeking intellectual fulfilment and civic duty outside the home.

The Des Moines club started the city’s first art gallery and library, but some groups had radical goals like suffrage, child labour or temperance, while others saved icons of American architecture from demolition, including George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

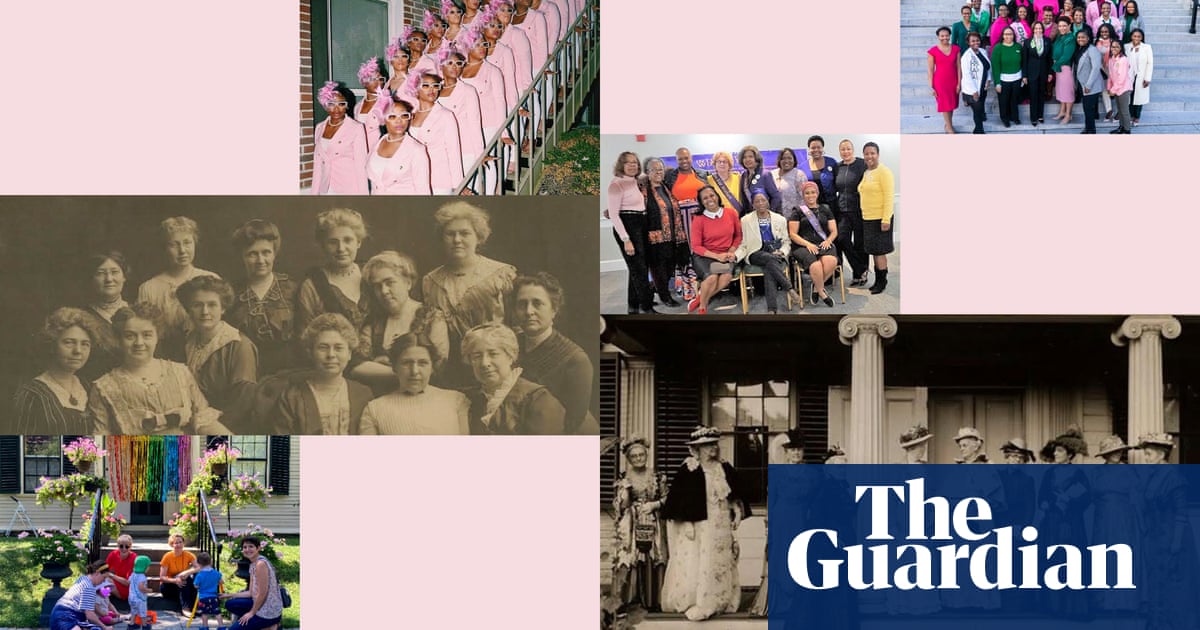

By the time the National Federation of Women’s Clubs (NFWC) formally endorsed votes for women in 1914, women’s clubs had an estimated 2 million members, declining in popularity in the 20th century after women entered the workforce.

Lorna Truck, 76, the Des Moines club’s historian, said: “They were social activists, ahead of their time. Our motto is: ‘Discussion stimulates thought’. At our peak we had 1,400 members.”

All of whom were white.

The retired librarian who still meets about 80 members twice a month to take part in talks and programs, added: “There were social restrictions at the time. We have Black members now, but for a long time there weren’t even any Jewish members.”

The United States’ 19th-century women’s club movement has both inspiring and complicated legacies. Many fought for civil rights, but in ways that were segregated. The clubs that still exist are now changing, becoming more diverse and also grappling with some of the legacies of their own racist pasts.

“Black women were either deliberately excluded or didn’t feel welcome,” said Alison Parker, a historian and expert in 19th-century women’s clubs at the University of Delaware. “Some white women were doing radical things under a cloak of respectability that helped change America. But then they were often exhibiting racism and not living up to their own ideals.”

She added: “African American women also had different concerns … like lynching, segregation, the right of Black men to vote, too [after they lost it de facto following the end of Reconstruction]. They tried to say … ‘your focus on suffrage needs to be more expansive and inclusive,’ but most white women were completely uninterested. So, they started their own groups.”

One of which was the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC), founded in 1896 by the Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman, the suffragist Mary Church Terrell, the activist poet Frances EW Harper and the journalist and anti-lynching campaigner Ida B Wells, as an empowering space to fight for full citizenship.

In 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, the NACWC joined thousands in front of the White House in the country’s first suffrage march.

By 2009, they hosted a pre-inaugural reception for Barack Obama.

In July, the NACWC celebrated its 128th anniversary and posted its motto on Instagram: “#liftingasweclimb.”

Karen Weinstein, the co-president of the Berkeley, California, branch of the American Association of University Women, founded nationally in 1881 and which excluded Black female graduates in some branches until 1949, said: “Because of their slowness to change, the white women clubs eventually lost their role as major players on the national stage, whereas the African American groups are still important today. Acknowledging our past is an important step because it allows you to move forward. It’s a problem that has not yet been solved.”

Two formerly all-white women’s clubs in Massachusetts are attempting to do that.

In Boston, the Jamaica Plain Tuesday Club, founded in 1896, is celebrating this week with 1,000 guests at a free, community party marking 100 years since it saved the 18th-century Loring Greenough House from demolition in 1924, after the daring women inexplicably raised $50,000 (the equivalent of $1m) to buy it, 50 years before they had the right to a line of credit.

Previously largely a club for donating to good causes, preserving the house and holding a weekly tea (on Tuesdays, of course), in recent years it has morphed into a socially conscious, mixed-sex, volunteer-run non-profit led by its first African American and LGBTQ+ co-presidents.

In 2022 the club made headlines after its drag queen story time was picketed by neo-Nazis, and is now actively shining a light on its uncomfortable history by publishing private records and conducting research and public talks on the Loring Greenough House’s connections to slavery.

“It’s been a busy few years,” said the board member Lorie Komlyn.

A second group that could become a national model for change is the Randolph Women’s Club. Founded in 1855 as a library for all-white, Protestant women in the town of Randolph outside Boston, the club, which once wouldn’t even let Catholics join, is now run by a majority-Black female board.

Marie Dyer, 70, the vice-president from 2021 to 2024, said the metamorphosis happened during Covid in 2020 when there was a “white exodus” of members who “thought the club would shut without them”, leaving a power vacuum filled by Black women.

The nurse and Haitian immigrant said: “It’s a total 360 turn from what it was. The whole leadership changed to Black; it was so sudden people were like, ‘what is happening?’ The problem was they just did not change quickly enough; they should have tried to find younger people and a diverse community, because Randolph is very diverse now.”

The club now has about 50 members and along with applying for grants to restore its 1806 club house and hosting feminist events, Dyer said its members were repairing the club’s “soul”.

“Our mission is getting women together. We need education, outreach, collaboration; it feels like a very special time for Black women.”