It was a “disaster”. It was “so drastically wrong”. Its creator was “ashamed” and “embarrassed”. “No one will ever see it.” It was “bad, bad, bad”. The film that triggered this outpouring was Jerry Lewis’s catastrophic Holocaust drama The Day the Clown Cried. Shot in the early 1970s, it has notoriously never been officially released in any form, and only tiny snippets of footage have ever made their way into the public arena.

Lewis, at that point in his career, was trying to reinvent himself after his zany-comedy persona of the 50s and 60s was no longer so popular. He got interested in the project and cast himself as Helmut Doork, a down-at-heel clown who ends up in a Nazi death camp where he leads 65 children into the gas chamber. The story behind the notorious production is told in From Darkness to Light, a new documentary directed by Eric Friedler and Michael Lurie and premiering at the Venice film festival, which promises to at last get to grips with the mysterious story of why The Day the Clown Cried was never shown in cinemas.

Toe-curling clips explain at least part of the reason, with Lewis’s clown pretending his nose is caught in barbed wire to amuse the kids, and doing a Pied Piper routine at the gas chamber door; these suggest he was right to keep The Day the Clown Cried off the screen on taste grounds alone. There were also familiar industry reasons behind the picture’s abandonment: contractual disputes, wrangles with producers and writers, money problems and creative differences. Most crucially, Lewis wasn’t in full possession of the rights to the script when he began shooting.

All of this, though, could theoretically have been overcome – if Lewis had wanted his film seen. As the documentary reveals, the star already knew that he had a disaster on his hands. When he spoke to Friedler a year before his death aged 91 in 2017, he was brutally candid about one of the biggest catastrophes of his career. He admitted he was “ashamed” of his own film … “For the lack of a better word, ashamed, embarrassed. Why? Because it was not good work. It was bad work on behalf of the writer, the director, the actor …”

All these roles, of course, were filled by Lewis himself. His ambition to make a serious statement with the film was not in doubt. When he headed to Sweden to work on it, he called up no other than Ingmar Bergman for advice about the best local actors to cast; partly on Bergman’s recommendation, Lewis cast Cries and Whispers star Harriet Andersson as Helmut’s wife.

Furthermore, the subject matter was obviously sensitive in the extreme. In the early 70s, few mainstream film-makers had dared grapple with the Holocaust. The Day the Clown Cried was made well in advance of Marathon Man (1976), The Boys from Brazil (1978) and Holocaust, the 1978 TV miniseries starring Meryl Streep. Scenes set inside the death camps were even harder to pull off: Sophie’s Choice, also starring Streep, came out in 1982, Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List in 1993. Lewis’s film was shot a full quarter of a century before Italian funnyman Roberto Benigni’s Oscar-winning Life Is Beautiful (1997), to which it bears obvious similarities.

Film-makers had generally kept comedy and the Third Reich well apart. Mel Brooks, who is interviewed in the documentary, had invented the Springtime for Hitler musical, and its outrageous kick-line routine, for his Broadway comedy The Producers (1967), and returned to the subject in the 1983 movie To Be or Not to Be , which was a remake of a 1942 wartime comedy starring Jack Benny and Carole Lombard. But as Martin Scorsese told Friedler and Lurie: “[Lewis] was completely stepping into an area that was … use the word taboo. The point is that no one had gone there before.”

Lewis is shown appearing on American chatshows in the early 1970s, breezily claiming the project would soon be completed. However, the emotionally shattered writer-director-comedian had in fact fled his own set with reels of the film under his arm. He wasn’t letting anybody see it. His footage was eventually donated to at the Library of Congress with an agreement not to show it until at least 2024; although there is little prospect of a public screening, the library may make it available to researchers. Some of the material has been in circulation. Comedian Harry Shearer says he saw a rough cut in the late 1970s on a bootleg VHS. But the documentary makers say that nothing approaching a final version was ever completed. “There will never be a total cut of the movie just because certain scenes were never shot. It will always be incomplete,” says producer Thore Vollert.

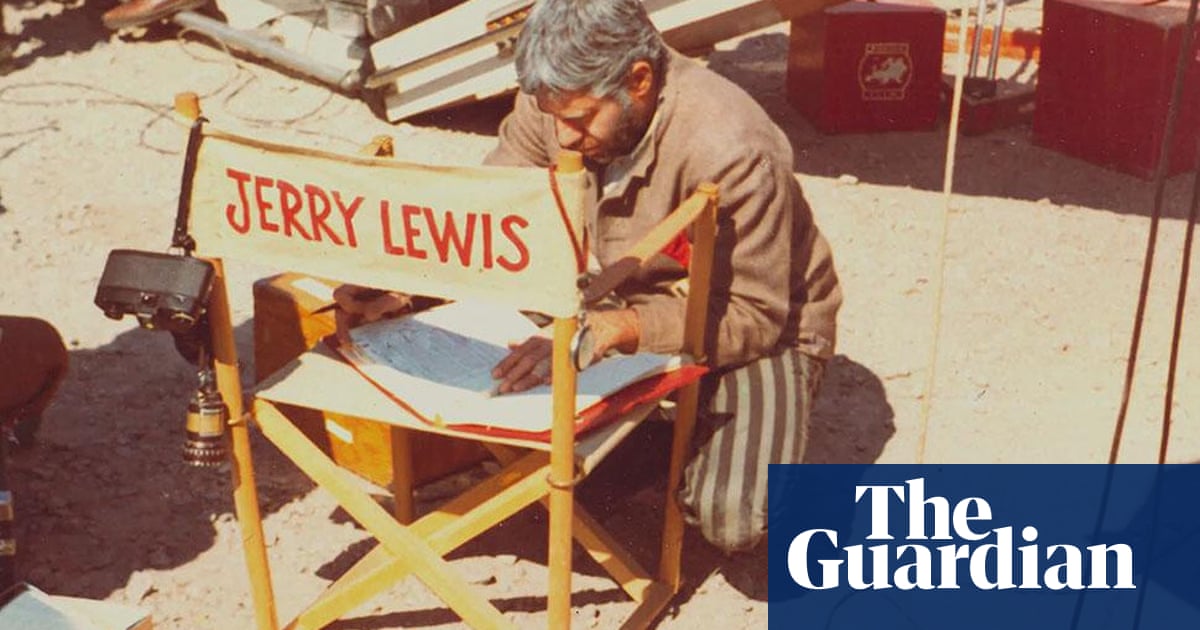

What remains are fascinating fragments: outtakes, the exquisite miniature set models, the production photos (one shows Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg with Lewis in Paris) and the often contradictory reminiscences of those involved in the project.

after newsletter promotion

For a while, it looked as if the documentary itself would stall. Its main interviewees – Lewis and Betty Blue director Jean-Jacques Beineix, who as a young man worked as Lewis’s assistant – died before it was completed. Friedler was determined to ensure Scorsese, who revived Lewis’s career in The King of Comedy (1982), was part of the film. “It was very important for us that Scorsese participated,” Friedler says. But it took years to get him on camera. The Scorsese interview, brokered by the documentary’s executive producer Wim Wenders, finally took place at the Berlin film festival earlier this year.

By a quirk of Hollywood timing, another movie based on the original script of The Day the Clown Cried has just been announced by producer Kia Jam. Even if Lewis’s project is well beyond salvage, the fact that its story is now being told might at least be posthumous consolation for him; he once admitted that not a day went by when he didn’t think about the film that had caused him so much pain and grief.