Brooke Bond Lipton merged with Hindustan Unilever in 1994

Brooke Bond Lipton merged with Hindustan Unilever in 1994

In the nine decades that Hindustan Unilever has been a part of the Indian business landscape, it has managed to achieve a rare distinction reserved for very few Indian businesses. The purveyors and users of its products don’t think of it as a multinational company. Instead, they think of its products as Indian, its managers as Indian and its owners as Indian.

While all three of the above may not always be true, it shows the extent to which the company has worked to adapt to the Indian consumer. In the company’s own words, it aims to ‘do well by doing good’.

It’s a journey that started in 1933 as Lever Brothers India Limited when the Swadeshi movement was at its peak and a rise in import duties meant that sales of the Sunlight soap—first introduced in England to reduce the drudgery of washing clothes—fell to record lows. It was then that Andrew Knox of the Overseas Committee of Unilever said, “The decision was taken to start manufacturing in India, which was not cheap inherently, but was the cheaper option when freight and import duties of 25 percent were taken into account.”

At that time, though, the company was run by managers from the parent; it was among the first multinationals to go public in 1956—557,000 or 10 percent of the outstanding share capital went in public hands and 21,673 Indians became shareholders. This contributed to the company Indian-ising over the years.

At that time, though, the company was run by managers from the parent; it was among the first multinationals to go public in 1956—557,000 or 10 percent of the outstanding share capital went in public hands and 21,673 Indians became shareholders. This contributed to the company Indian-ising over the years.

But the journey was not without its ups and downs. Among the first was the price control order on soaps that came during the Chairmanship of T Thomas starting 1973. At that time, the company had two major businesses—soaps and Vanaspati. Both were under price control and the situation meant that in 1974, the company registered its first loss. Naturally the Indian managers were concerned about the fact that the parent might lose interest in the India business. T Thomas met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who asked him how much the company could produce a new ‘janta soap’ for. He gave her a price that was 50 percent more than the controlled price.

Aware of the bad publicity that soap shortage had created for her government, she asked Thomas to resume full production overnight and decontrolled the price. This period also taught the government that shortages could be eliminated if the right incentives were created for companies. One by one prices of most products were decontrolled.

The company faced another stern test when under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, it had to reduce the shareholding of its parent to 40 percent. This was a period when several multinationals like Coca-Cola and IBM exited India. After several meetings in Delhi, the government agreed to allow Unilever to maintain 51 percent shareholding provided that 60 percent of its business was in its ‘core sector’ and 10 percent in exports.

As Hindustan Unilever continued to grow, the late 1980s and early 1990s were a heady time as both organic growth as well as mergers and acquisitions ensued.

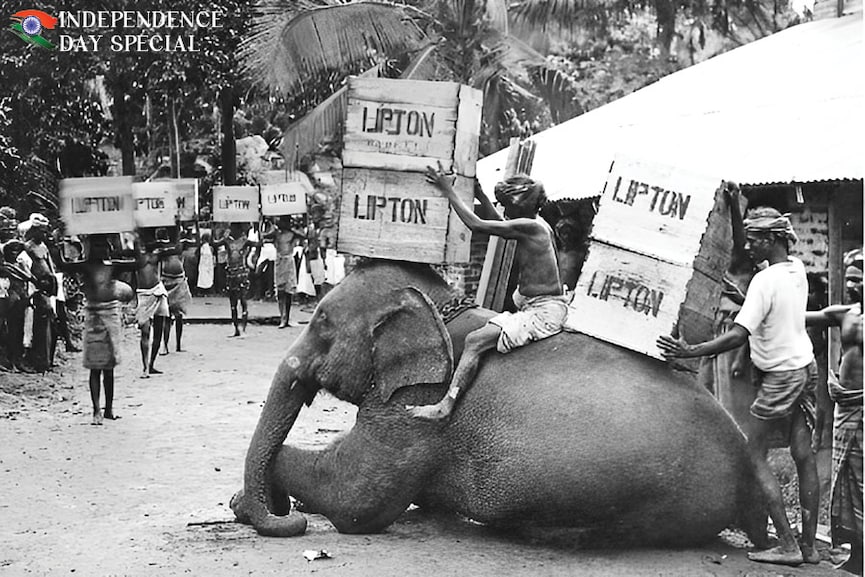

Chairman SM Dutta writes in a special book to commemorate 75 years of the company, “(While) I would certainly like to reminisce about the mergers and acquisitions that brought us a lot of media attention, but let us not forget the enormous thirst for organic growth.” During this period, there was the acquisition of TOMCO (Tata Oil Mills Company), the Kissan brand from United Breweries and Dollops ice cream from Cadburys. And in 1994, Brooke Bond Lipton merged with Hindustan Unilever.

Also read: Bata’s transformation for the aspiring modern Indian

This was also the 1991 post-liberalisation era when quotas were lifted and companies like Hindustan Lever could expand based on demand. The challenge of homegrown detergent brand Nirma was seen through with the launch of Wheel, and Lifebuoy, after a poor start, was re-launched and became the largest selling soap brand in the world at that time.

Throughout the 1970s, the Hindustan Unilever research center pioneered the use of indigenous materials in soapmaking to reduce India’s reliance on costly tallow imports

Throughout the 1970s, the Hindustan Unilever research center pioneered the use of indigenous materials in soapmaking to reduce India’s reliance on costly tallow imports

Hindustan Lever’s next challenge came in the 2000s when consumers suddenly had other avenues to spend. MS Banga, chairman during this time, writes about how interest rates fell from 18 percent to 10 percent, bringing easy access to consumer finance. One could drive out of a Maruti showroom after paying just ₹2,000 as down payment for a car. Mobile phone usage exploded. “It’s not that people bathed less or brushed their teeth less or washed their clothes less. But they did downtrade from higher quality brands to lower priced substitutes,” he writes. The company came up with the ‘power brand’ strategy where the focus was brought down to 35 brands from 110 that the company had. Some like Surf Excel were re-launched and others like Lifebuoy revamped. Growth resumed in the latter half of the decade.

As Hindustan Unilever (the name was changed in 2007) grew, it also needed to constantly innovate. There was Project Shakti—women in villages who would sell the company products and earn their livelihoods, the trebling of its rural direct distribution reach to 637,000 villages as well as Kan Khajura Tesan, a missed call campaign where consumers could make a ‘missed call’ to a number and receive a call back with advertising information for a product. In the pre-smartphone era, it was a hugely successful venture.

Nine decades after its founding in 1933, Hindustan Unilever is a jewel in Unilever’s crown. While sticking to its core of soaps and detergents, and food, the company has also successfully made its products acceptable to Indian customers. For instance, it has some ayurvedic offerings through Lever Ayush.

In 2013, the parent increased its stake in the Indian subsidiary to 61.9 percent through a hugely successful buyback at ₹600 a share. In the 11 years since, the company has returned 14 percent a year to its shareholders, taking its market capitalisation to ₹635,000 crore, making it the largest consumer goods company in India.

(This story appears in the 23 August, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)