Responding to criticism of India’s “big brother diplomacy” in its neighbourhood, I would often invite my fellow South Asian interlocutors to think of an alternative metaphor. Replace the term “big brother”, a concept that comes with its very Indian joint family cultural baggage, with “tall person”. A six-footer in a group of five and odd feet wallahs has the disadvantage of bending neck to interact with shorter persons.

The shorter ones are entitled to ask: “Why are you looking down on us?” The tall one has no option. A parent can kneel down to engage a child face-to-face, but big nations have difficulty kneeling.

Developed countries pretend to treat the developing ones as equals but everyone knows that the world is made of unequals. While pretending to be equals, nations big and small have to have the wisdom to recognise the fact of inequality and deal with it. Just as India has to learn to deal with its smaller South Asian neighbours, they too must learn to deal with a bigger India. The same argument applies to India-China relations.

Indian politicians, diplomats and the elite at large have a problem in this regard. They are quite willing to live with the reality of a longer duration development and power imbalance in the country’s relations with the West. But they find it difficult to deal with the more recently emerged imbalance with regard to the People’s Republic of China.

Through most of the first three quarters of the 20th century, India and China were more or less at the same level of development. In the last quarter, however, China began to move gradually ahead, but not significantly. Even as late as 2007, Singapore’s founder-leader Lee Kuan Yew referred to the two Asian giants as two engines of the Asian plane and believed that for Asia to rise and regain its historical status in the 21st century, it must fire on both engines.

Similar views expressed even by Chinese leaders during the period 1980 to 2010 gave comfort to the Indian elites. This attitude also enabled the two countries to arrive at a modus vivendi on the border question. However, after the trans-Atlantic financial crisis of 2008-09, things changed. China took off, to use an airline metaphor made popular by the economist Walt Rostow. Even in 2005 when Prime Ministers Manmohan Singh and Wen Jiabao met, they would relate to each other as equals. By

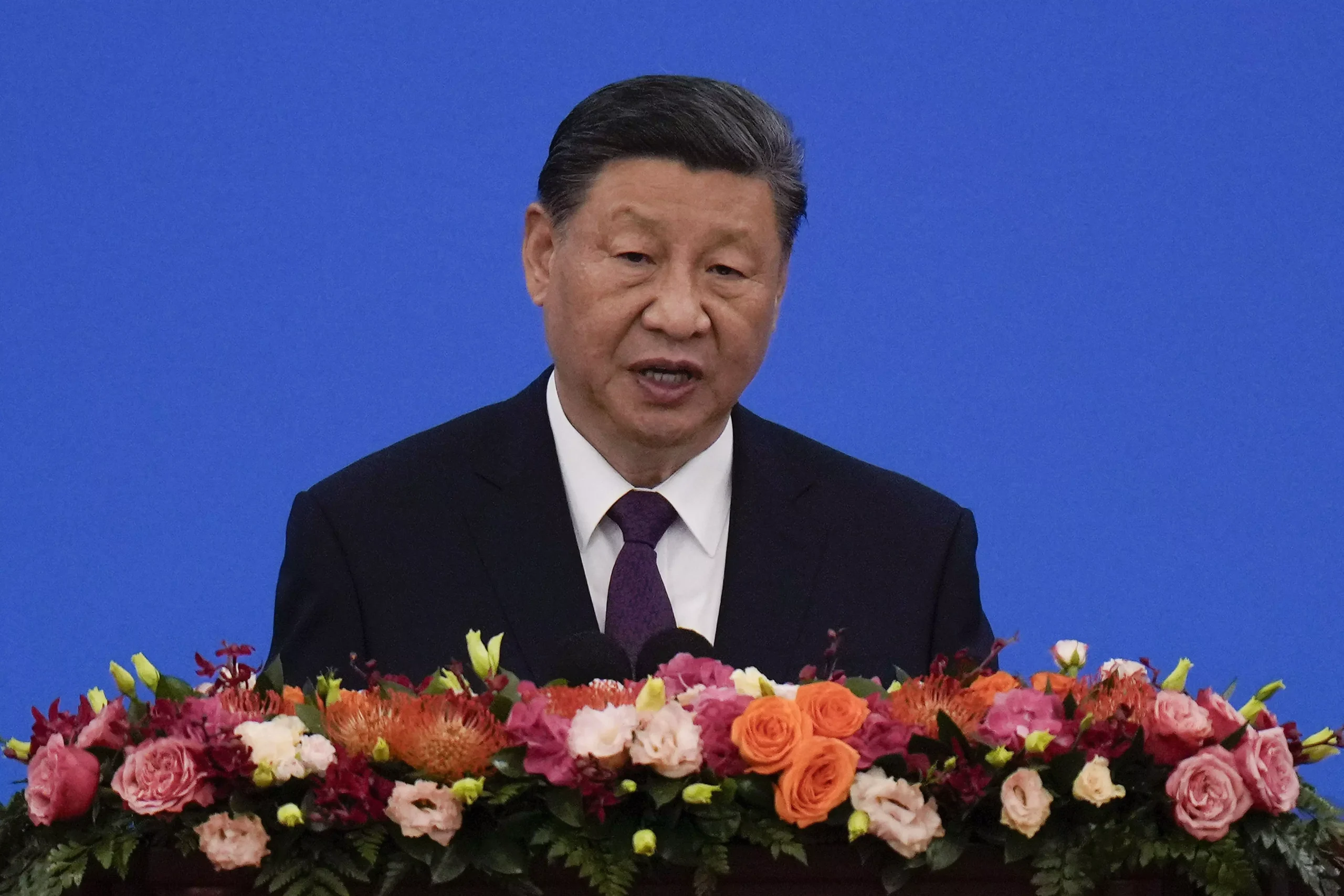

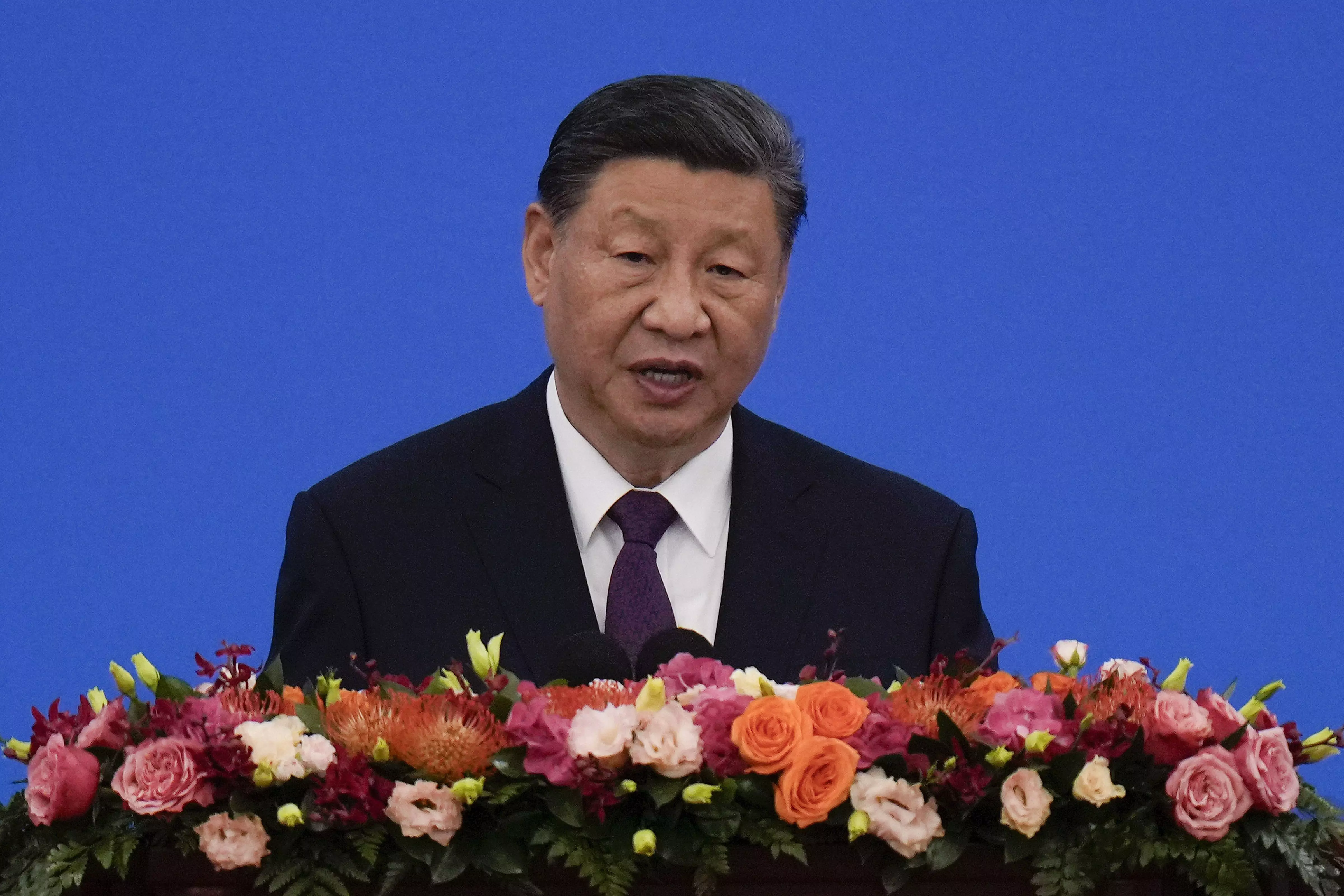

the time President Xi Jinping met Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014, the balance had tilted in China’s favour. Over the past decade the Chinese economy has become five times bigger than India’s.

In 2010-11, I had the opportunity of participating in a trilateral dialogue between think tanks in China, India and the United States. The dialogue began with a question from a young Chinese scholar. I can understand, he said, why China and the United States must engage in a dialogue. “China is a rising power. The US is a declining power. We need to manage this transition. But, why do we have India at this table?”

President Xi pursued that question by making it clear that India and China are no longer in the same league. China will henceforth engage the US directly and as an equal. India is no longer entitled to a seat at that table. The Indian leadership and intellectuals have found accepting the changed reality difficult.

Perhaps President Xi Jinping’s decision to dump the understanding on the border issue and allow his People’s Liberation Army to walk into disputed territory in the Ladakh region in June 2020 was meant to, what some regard as, “show India its place”. This has quite understandably rankled India. The impasse in the bilateral relationship has continued since then. India expects China to say mea culpa and walk back. But Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s statement in June 2020 gave China a free pass. Mr Modi had said: “Neither have they intruded into our border, nor has any post been taken over by them (China). Twenty of our jawans were martyred, but those who dared Bharat Mata, they were taught a lesson.”

While government-to-government (G2G) discussions on the border issue have been going on, two contradictory features have come to define the state of India-China relations. One the one hand, business-to-business (B2B) relations are thriving. Bilateral trade is booming and the Union government’s annual Economic Survey has suggested that India should be more open to Chinese investments. What has suffered most as a consequence of President Xi’s ill-advised move in June 2020 is people-to-people (P2P) contacts. While Beijing has resumed the issue of tourist and business visas, New Delhi remains stingy on both counts and direct flights remain suspended, raising the cost of travel.

Both the BJP and the Congress Party should take relations with both the United States and China out of domestic political rivalry and agree to a shared approach. Every government has its share of achievements and mistakes in foreign policy. On relations with the US and China the governments led by both parties have had their achievements and made their mistakes over the past three decades. Both have served the national interest. Rather than constant bickering on who did what, it would be in India’s interests to have a balanced approach to relations with the two major world powers: the US and China.

We seek the emergence of a multipolar world and a multipolar Asia. That can happen only when the Indian economy is bigger, more productive and dynamic.

Much of the work lies at home. Both the US and China can play a role in the revitalisation of the Indian economy. There is already a political consensus in India among major political parties on the positive role that the US can play in India’s economic rise. There is a similar need for a consensus on the China policy. Recent statements and policy actions emanating from New Delhi suggest a thaw. This should embrace all aspects of the bilateral relationship — G2G, B2B and P2P – even as we maintain our vigilance across the high Himalayas, modernise our border infrastructure and keep the powder dry.