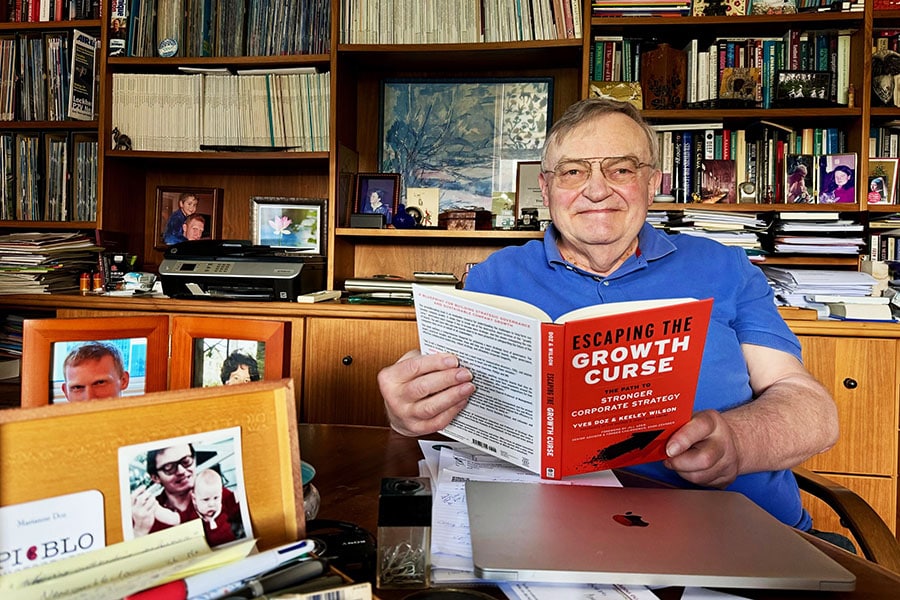

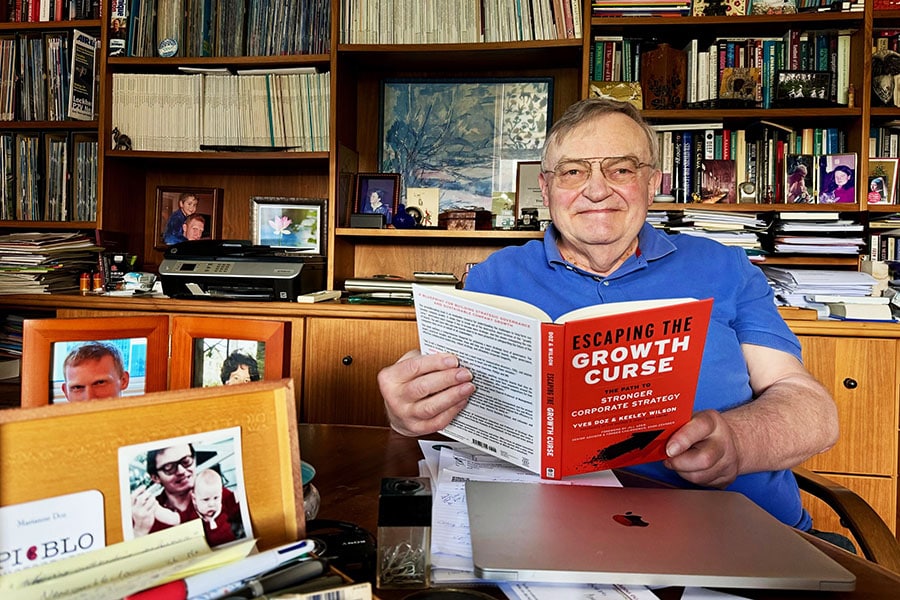

Yves L Doz, Emeritus professor of strategic management, INSEAD

Yves L Doz, Emeritus professor of strategic management, INSEAD

Yves L Doz is emeritus professor of strategic management, INSEAD and the Solvay Chaired professor of technological innovation, emeritus. He is also co-author of Escaping the Growth Curse: The Path to Stronger Corporate Strategy. In an interview with Forbes India, he talks about the potential that boards hold for safeguarding a company’s future. Edited excerpts:

Q. What is the ‘growth trap’ companies in which companies get caught?

Managements often nurture expectations among investors, analysts, and even the board that growth (in value, earnings, sales) can, and will, continue unabated from quarter to quarter. But a company’s growth cannot last forever. Markets mature, new competitors enter the markets, breakthrough innovations create new means of providing similar value to customers, etc. Expectations meet reality, and the company’s performance in a growth stall is bound to disappoint investors.

Q. What’s the vicious cycle this leads to?

The growth trap turns into a vicious circle we call a “growth curse” when management keeps promising growth, even when such growth is no longer feasible (and new growth avenues have not been found or pursued successfully) and engage in “window dressing” — still showing growth but at the cost of further compromising the company’s longer-term future. Cutting strategic expenditures, such as R&D or brand promotion, is an obvious temptation as is using share buybacks to inflate the stock price artificially. Under growing pressure, management may engage in increasingly borderline or downright fraudulent accounting practices. Business unit heads and middle managers are put under growing performance pressures and fear top management demands against which they can’t deliver. This often leads them to optimistic – and inaccurate – reporting. The management reporting system stops being reliable, and fear, lies, and corruption spread.

Q. How are boards adding to the problem?

Boards can contribute to the problem in various ways: First, they may not detect the onset of a growth curse, being too distant from management, and too formal in interactions. A strong, charismatic CEO can dominate the board, particularly when he/she is also the chairperson. As in Nokia, under Jorma Ollila’s leadership, what is discussed on the board, and the image projected by management became divorced from a deteriorating reality within the company. Second, a board may also let a CEO down by not shielding the CEO from the most stringent demands made by shareholders or, in particular, other “active” investors. Rather than protecting management from external pressures, they amplify them.

Q. When growth stalls, what’s the right approach for a board?

The first requirement is to investigate the source(s) of the growth stall with management, but not rely entirely on management. The board needs to develop a distinct analysis identifying the problem(s) at the origin of the growth stall. On an aggregate basis, half of poor strategic decisions result from a deficient understanding of the problems faced by the company. However, an effective board will not wait for a growth stall to consider strategy but will be engaged with management or strategic issues on an ongoing basis.

One of the European companies we researched has developed a structured process for the non-executive board to contribute to strategy-making without prevailing over management. Once a year, it holds a joint strategy discussion between the supervisory and the executive boards. In preparation for that meeting, the company’s strategy staff will carry out a round of interviews with the directors focussed on strategic issues. They then articulate a strategy that proposes several alternatives for key issues identified by management and directors that vary in intensity — some requiring little action, others demanding major efforts.

On the strategy day, the board is given four action options on each key issue and analyses and explanations that allow them to understand the thinking behind each plus a recommendation from management regarding the preferred option. Only after the preferred options have been selected is the strategy translated into a midterm financial plan and resource allocation choices set. Thus, management and the board are given time to first consider fundamental choices. Directors bring different inputs, from different perspectives, adding an “outside-in” perspective, and management is transparent about key choices. Directors discuss action proposals but do not tell management what to do. It is only later that P&L implications and resource allocation trade-offs are considered. It is a transparent, interactive process. Additionally, at every board meeting, there is a major strategic issue introduced for a “deep dive” discussion – for example, restructuring supplier networks.

Also read: As AI moves to change everything, you need a strong, informed board of directors

Most importantly, when sustaining a good grasp of the strategic issues facing a company, an effective board will bring a greater peripheral vision (what some call “dragonfly eyes”) and sensitivity to emerging challenges and opportunities on a wider scope than that considered by management. The point is not for the board to investigate these issues in depth – directors lack the time and most boards do not have significant budgets for staff or consultants – but to alert management to them, particularly when management might be blindsided.

A growth stall may also result from internal weaknesses in talent, processes, technology, etc. Here, directors need to be legitimate when in contact with executives one or two levels below the CEO, and gain an understanding of their skills and competencies, and of leadership or management process deficiencies.

Q. What are a company’s ‘strategic assets’? How can they be leveraged in the face of disruption?

In essence, strategic assets provide a company with valuable and hard-to-replace resources that competitors would unsuccessfully strive to emulate or substitute. In its simplest form, privileged access to raw material is the crudest form of strategic assets, be it oil at a low extraction cost in Saudi Arabia (until the energy transformation) or diamonds in Botswana (until synthetic diamonds become undistinguishable from natural ones). More importantly for most corporations today, strategic assets are collectively held competencies deeply embedded in organisational know-how and management methods. For instance, in contrast to Kodak, Fuji Photo film, faced with the same digital disruption, was quick to identify strategic assets and use them to build new businesses in six areas, such as medical systems, life sciences, or optical equipment. It recombined skills in chemistry, optics, and mechanics to redeploy itself successfully.

Q. What direction should a strategic board take vis-à-vis succession planning and risk assessment?

On succession planning, start early—make time your ally, and make succession planning an ongoing process, just in case. CEO succession requires time to consider the required profile and skills, to search externally and internally, to assess candidates, and to develop and appoint them. The key issue is to avoid bad surprises and to be ready by not starting a process from scratch when the need arises: accidents happen; diseases strike; a CEO can be disabled overnight.

On risk assessment, the board can use its wider angle of vision to identify potential “black swans” and low-probability events that would have dire consequences. Management, mobilised into action, usually tends to minimise these risks or treat them fatalistically as “acts of god”. In today’s conflictual and unstable geopolitical configurations, we need to pay more attention to not-so-likely — but devastating — events such as, for instance, a China-US war over Taiwan (and the control of the world’s semiconductor industry).

Climate change is likely to create more and more disruptions, as we witnessed in Europe with shipping on the Rhine having to be interrupted because of draughts and chemical plants in Germany having to stop production. The board should constantly remind top management of these “black swan” risks and encourage it to develop and update “catastrophic scenario” planning.

Q. Ways to find new S-curves…

Some highly successful companies in very different industries, from industrial to medical equipment (eg, Danaher in the US) to luxury goods (e.g., LVMH in France) have developed effective growth models by acquiring smaller companies whose strategic assets (be they products, technologies, or brand images) are under-leveraged. They then bring strong professional management to these, with improved productivity, brand marketing, or other skills, and have them each start a new, small “S” curve. Active portfolio management enables high performance and provides the resources for further acquisition. Private equity firms are merely systematising this approach further with higher performance improvement demands.