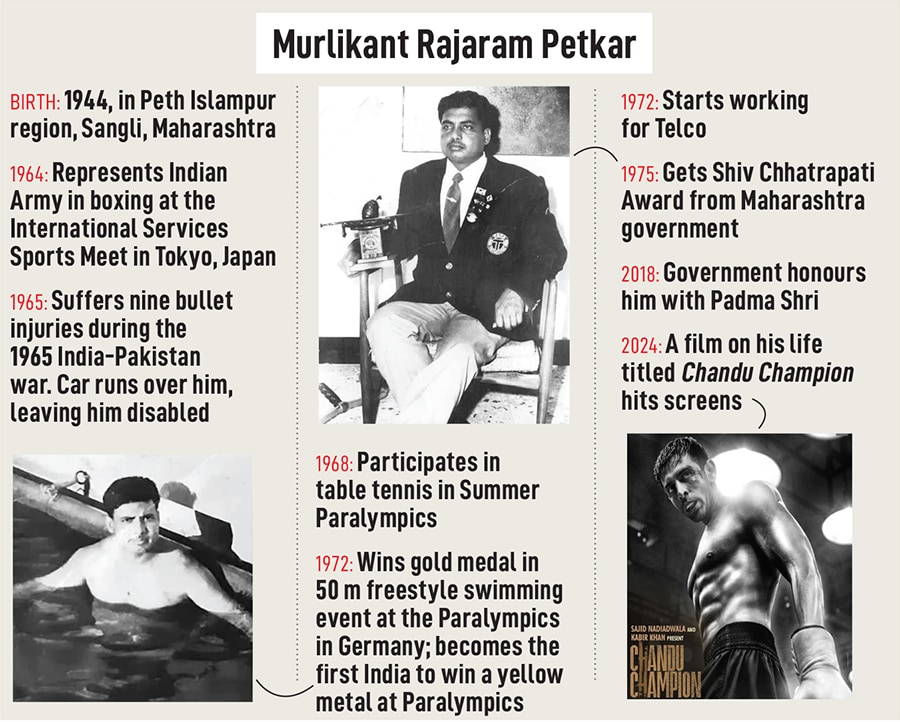

Murlikant Rajaram Petkar, India’s first Paralympic gold medalist, receives the Padma Shri from President Ram Nath Kovind in 2018

Image: Ajay Aggarwal/Hindustan Times Via Getty Images

Murlikant Rajaram Petkar vividly remembers the euphoria following Khashaba Dadasaheb Jadhav’s Olympic win in 1952. The latter became the first individual athlete in Independent India to bag a medal at the Games—a bronze in wrestling at Helsinki, Finland. Jadhav got a rousing reception when he reached his village, Karad, in Satara, Maharashtra. Among the 5,000-odd people gathered at the railway station to welcome the sporting hero was Petkar, then eight years old, sitting on the shoulders of his brother, trying to catch a glimpse of Jadhav.

“The victory celebration was unbelievable. We travelled 20 km from my village, Peth Islampur in Sangli, just to see Jadhav, whose achievement had made India proud. There was tremendous energy and enthusiasm among the people gathered there. Taken in by the response to his win and the fervour among people, I decided there and then that I will also win a medal for my country,” Petkar, now 79, tells Forbes India.

The idea seemed implausible in the India seven decades ago. Not only was survival and financial security top priority, but also there was a near-absence of sporting infrastructure. No wonder Petkar faced a lot of jeers and sneers when he openly expressed his ambition in school. When asked what would they like to become when they grow up, some of his classmates gave the ‘usual’ answers—doctor, teacher, Army personnel. “I said I want to become an Olympic gold medallist,” recalls Petkar, adding that the class burst into laughter and subsequently, he was subjected to public humiliation in his village too.

He was determined, though, and first began with wrestling, a sport that came naturally to him. His strength, technique and reflexes improved as he became a regular at Jadhav’s training centre that was set up in his village. He was academically weak, so sport gave him a sense of confidence—he felt good at winning wrestling bouts with ease. He once defeated the sarpanch’s son in a match. It was blasphemy in a way as the power equations then meant that the rich and influential cannot lose face. Petkar had to flee the village within minutes as he was chased by the sarpanch’s men.

The youngster took a train to Pune, where his paternal aunt resided. She got him enrolled in the Boys Battalion of the Indian Army in due course. There, he lost touch with wrestling as the sport wasn’t being played there, but took to hockey. He laments that politics and partiality meant he was never selected for the team. One afternoon when he was shedding copious tears at being ignored, a senior advised him to “stop crying like a baby” and go on the other side where boxing selections were taking place.

“Use your power and pent-up energy there. Knock off your opponents one by one,” he advised. Petkar excelled in boxing in no time. In 1964, he represented the Indian Army at the International Services Sports Meet in Tokyo, Japan. “I won 15 fights there… a boxer from Uganda beat me in the final,” he claims.

On his return, he was posted in Secunderabad, and later asked where he’d like to go. Petkar chose Kashmir and was in the Valley for over a year before tragedy struck. During the 1965 India-Pakistan war, an alarm went off early one evening to indicate an imminent attack. “Unfortunately, many came out of their bunkers thinking it was tea time,” says Petkar, who was a jawan in the Corps of Electronics and Mechanical Engineers. The enemy, by then, had launched a full-blown aerial attack, leaving Indian Army personnel scurrying for cover. Petkar suffered nine bullet wounds and was run over by a vehicle that left him paraplegic.

Also watch: Exclusive: Catching up with India’s star TT player ahead of the Paris Paralympics

He remained in coma for two years. And when he regained consciousness and saw Army officers around him, his first thought was that he was captured by the enemy. “My last memory was of the attack. I was stuck at the same place where I was two years ago in my head,” explains Petkar. The doctors at the INHS Ashwini Hospital in Colaba, Mumbai, told him he would have to live with a bullet in his spine.

Though disabled, Petkar vowed not to give up. He found hope when the doctors told him he could take up swimming to gain strength. Ignoring the naysayers, Petkar would practice in the hospital’s swimming pool daily. “Four people would take me on a wheelchair there. I learnt swimming in less than a month, and I was a master at it in three to four months,” he says. I wasn’t married, and didn’t have family support—they (he was one of six siblings) were in the village fending for themselves, he adds. “Happiness was my best friend. I chose to lead a happy life. I wasn’t sad or disappointed at the turn life had taken. I did not curse my destiny,” emphasises Petkar.

From 1968 to 1982, he took part in multiple international events, and in various sports—javelin, precision javelin throws, slalom. The crowning glory, though, came in 1972 when he won a gold in the 50 m freestyle swimming event in the Summer Paralympics held in Heidelberg, Germany. He set a new world record (37.33 seconds) and became the first Paralympic gold medallist from India. “I was mentally very strong. I was extremely confident that I would win… I could only see the medal,” says Petkar, adding that witnessing the Tricolour go up after his victory remains the happiest moment of his life.

Petkar created history in 1972 despite lack of sporting infrastructure. He hopes more academies are set up in rural areas

Petkar created history in 1972 despite lack of sporting infrastructure. He hopes more academies are set up in rural areas

Pandurang Patil, former swimming coach with the Pimpri-Chinchwad Municipal Corporation in Pune, trained Petkar for the first time in 1978, and has known him to date. “He was extremely focussed and was determined to lead a fruitful life,” he says. “He’s a jolly person, and a loyal friend. In fact, his vigour and optimism are infectious.”

Petkar’s son Arjun, a national level mountain climber, says his father embodies positivity. “He faced insurmountable obstacles and challenges, but he was never bitter about his experiences. Instead of losing hope, he turned adversity into a friend. Ultimately, he achieved his goal of winning an Olympic medal… circumstances, however, took him to the Paralympics,” he says.

His triumph, though, went unnoticed till Arjun, who now works for the defence services in an ammunition factory, created a website, highlighting Petkar’s success. The BBC subsequently did a story on him. “There’s hardly any interest in the achievements of handicapped people. I only got a bouquet on my return,” claims Petkar, who was awarded the Padma Shri in 2018, almost 50 years after the medal win. While conceding that facilities have improved compared to the time when he competed, he feels a lot still needs to be done. “For instance, more training centres should come up in villages. There’s greater talent in rural areas. If we have academies and the infrastructure there, we can win many more medals,” he says.

(This story appears in the 23 August, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)