(Left to right) Second-gen Abhishek Gupta, chief-strategic marketing, Trident Group, and Neha Gupta Bector, chairperson, myTrident, with their father Rajinder Gupta, chairman emeritus, Trident Group

(Left to right) Second-gen Abhishek Gupta, chief-strategic marketing, Trident Group, and Neha Gupta Bector, chairperson, myTrident, with their father Rajinder Gupta, chairman emeritus, Trident Group

Image: Madhu Kapparath

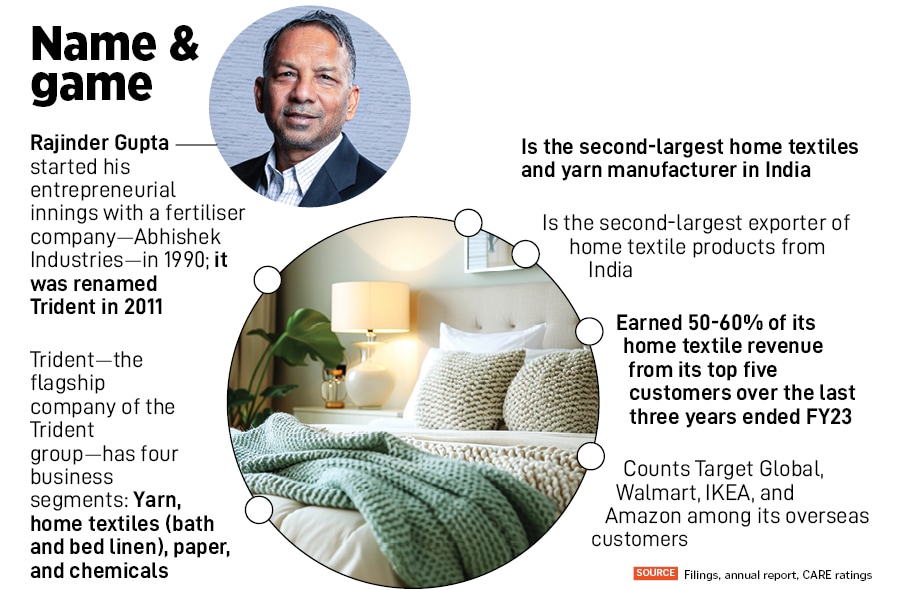

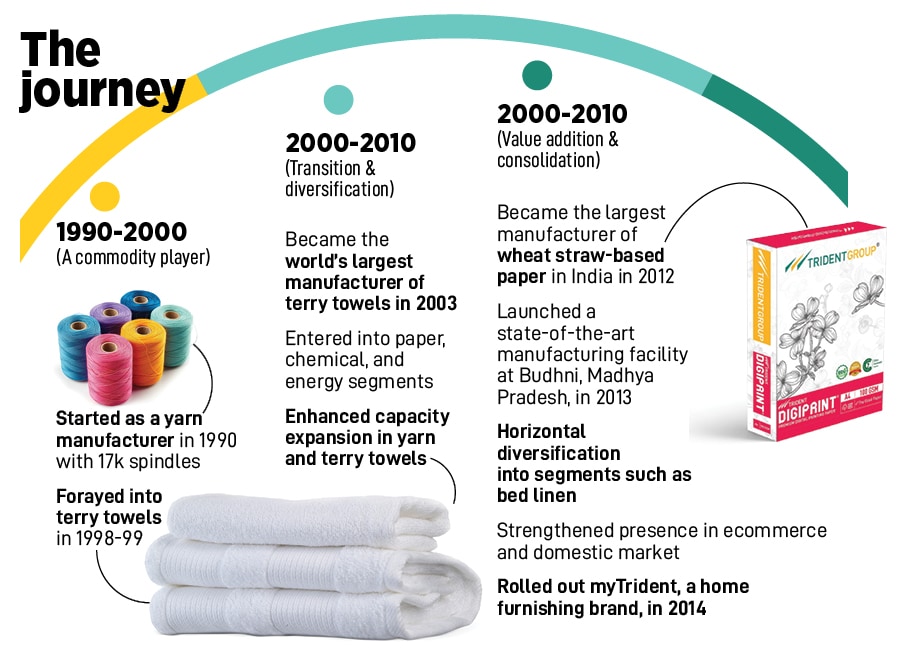

Can dissatisfaction trigger growth? Can a sense of uneasiness nudge a person to explore options? Can being too self-critical lead to bigger goals? Can over-ambition fuel progress? Is success possible without planning? A physical meeting with Rajinder Gupta can take you on a metaphysical trip. “My story can be summed up only in one way,” says the founder and chairman emeritus of the Trident Group, the second-largest exporter of home textile products from India, the world’s largest producer of terry towels, the world’s biggest wheat-straw-based paper manufacturer, and which counts Target, Walmart, Ikea, and Amazon among its overseas customers.

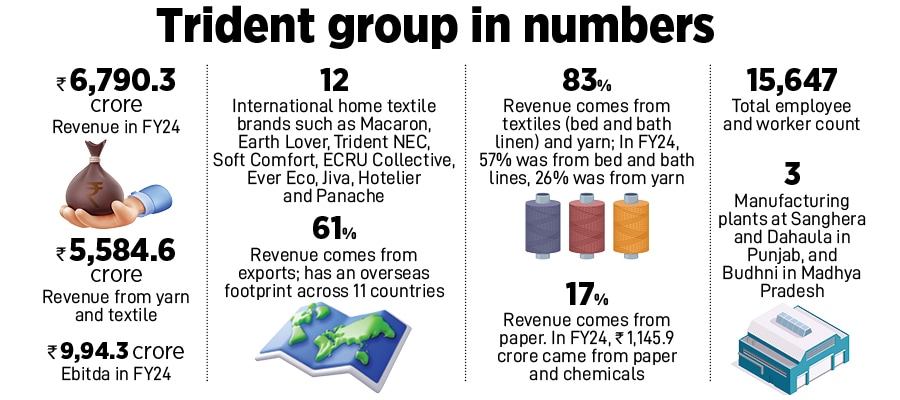

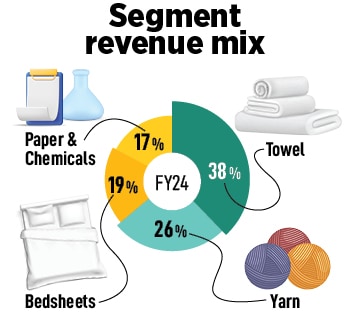

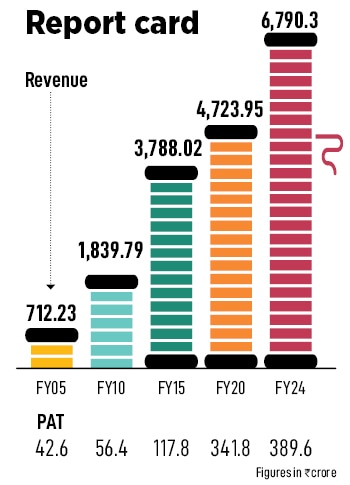

If a flurry of such global wins doesn’t entice you to know more about the company from Punjab that was born as a fertiliser firm—Abhishek Industries—in the late 80s, here’s another meaty nugget to grab your attention: 9x. The revenue of the diversified textiles, chemicals, and paper conglomerate has pole-vaulted from ₹712.23 crore in FY05 to a staggering ₹6,790.3 crore in FY24, a 9x jump in 19 years. PAT (profit after tax), too, soared 9x from ₹42.6 crore to ₹389.6 crore during the same period.

Despite a list of lofty achievements, the founder doesn’t sound pompous. The first-generation entrepreneur and self-made billionaire—ranked 1724 on the Forbes’ Billionaires List in 2024—continues to narrate an unpretentious version of his story. “Everything that happened was perchance and by chance,” says Gupta, popularly known as RG in the family, business, and trade circles. “Nothing was planned or aligned with any grand vision or mission. I just walked on the road laid out by the Almighty,” he adds.

For RG, it has been a long walk on a bumpy road. “We began with a small dealership, then moved on to small-scale manufacturing, and then just kept evolving,” he contends, adding that what helped him grow was a deep sense of dissatisfaction. “Maybe I was more ambitious than others or simply unhappy with whatever I was doing,” he says. “Even now, I’m not entirely happy with what I’m doing,” he says flashing an enigmatic smile.

I try to nudge the monk to talk about the hardships during his journey. From fertiliser to yarn, cotton, full-stack textile, chemicals, paper… was it a seamless transition and metamorphosis? How challenging was it for the first-time entrepreneur from a humble background who reportedly was forced to drop out of school and work odd jobs to make ends meet? RG doesn’t budge an inch. He stays in his detached zone. “Past is no longer relevant. When you’re not planning for something, you would be happy with whatever you have,” he says, adding that he encountered gusty headwinds, but he persisted. “What truly matters is one’s conviction and never-say-die attitude,” he says.

Tenacity played a big role in RG’s success. Back in the 80s and 90s, for a rookie entrepreneur without a family business background, it was almost impossible to get institutional backing. “I went to one of the prestigious bankers for a loan. He declined,” he recalls. The reasons for the rejection were cliched: No income tax returns, no collateral, and no formal employment track record. Other bankers too shied away. “But there was one who decided to take a bet on me,” he says.

Tenacity played a big role in RG’s success. Back in the 80s and 90s, for a rookie entrepreneur without a family business background, it was almost impossible to get institutional backing. “I went to one of the prestigious bankers for a loan. He declined,” he recalls. The reasons for the rejection were cliched: No income tax returns, no collateral, and no formal employment track record. Other bankers too shied away. “But there was one who decided to take a bet on me,” he says.

One turning point paved the way for another. In 1991, Punjab was under the governor’s rule, the state was aggressively planning to promote industries, and RG was roped in for a joint venture to set up a spindle mill at Barnala. The entrepreneur acknowledges the role and support of the state government in trusting the vision of the rookie founder. “Back in the old days, when we had a public issue, the state government trusted me and invested 26 percent equity, and the banks contributed another 25 percent,” he recounts, adding that it was one of the most successful public issues.

The textile manufacturing facility in Budhni in Madhya Pradesh

The textile manufacturing facility in Budhni in Madhya Pradesh

Destiny too played a part in shaping the rags-to-riches story of the son of the soil. “Imagine, I was an unknown entrepreneur, the banks underwrote the public issue, gave a bridge loan, and we repaid it,” he says, reiterating the divine role in shaping his entrepreneurial innings. “Looking back, it’s hard to imagine a state funding an entrepreneur who wasn’t bringing in any money from personal sources,” he says, adding that in 2011, Abhishek Industries was renamed Trident.

Luck, interestingly, was fortified with heavy doses of pluck. In the formative years, Trident was fighting the Goliaths: Tata, Birla, DCM, and a bunch of strong regional players in textile who had the first-mover advantage, a dominant retail presence, and deep financial clout. “I don’t want to sound haughty, but we managed to stay ahead of them,” says RG. He puts things in perspective: When Trident entered the spinning industry, it was largely dominated by a few well-established families from northern India. “No one from an unknown background ever ventured into this space,” he recounts. “We took on the challenge. We shattered the myth that only certain families could succeed in spinning,” he says.

As the journey gathered steam, Trident forayed into chemicals and papers. RG reckons the diversification happened by chance. “Our entry into the paper industry was serendipitous,” he says. The company had a sulfuric acid plant that produced a lot of steam. Somebody suggested the idea of setting up a small paper plant. “We didn’t settle for small. We aimed bigger. And it paid off,” says RG, adding that the Trident Group is the world’s largest wheat-straw-based paper manufacturer. “Each decision, whether spinning, paper, or chemicals, was about going beyond our limits,” he adds.

As the journey gathered steam, Trident forayed into chemicals and papers. RG reckons the diversification happened by chance. “Our entry into the paper industry was serendipitous,” he says. The company had a sulfuric acid plant that produced a lot of steam. Somebody suggested the idea of setting up a small paper plant. “We didn’t settle for small. We aimed bigger. And it paid off,” says RG, adding that the Trident Group is the world’s largest wheat-straw-based paper manufacturer. “Each decision, whether spinning, paper, or chemicals, was about going beyond our limits,” he adds.

The next-gen—his son and daughter—is cut from the same cloth and has inherited the tenacity and stubbornness. “Joining the business was always the normal and natural thing to do,” says Abhishek Gupta. “I just went with the flow,” he says. Unfortunately, the flow was choppy for a heavily export-oriented company. In October 2008, a month after the Lehman crisis, Gupta joined Trident. “This was my first big crisis,” he recalls. The commodities nosedived, prices tanked, and the apprentice had to make sense of the chaos around the world and business. “That’s something we had to live with,” he says. To make matters worse, there was huge volatility in the forex market. “It was a painful lesson. But you learn fast, move on, and don’t repeat the mistakes,” says the chief of strategic marketing at the Trident Group.

Also read: How the Katkar family built Quick Heal into India’s largest consumer antivirus brand

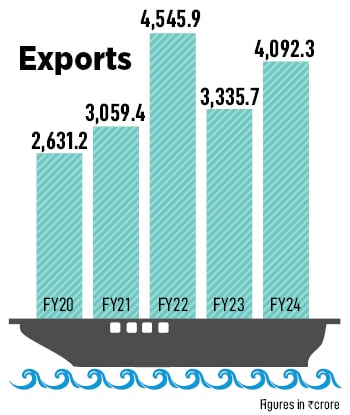

Another quick learning was that the entrepreneur was all by himself. The second-gen entrepreneur had an inornate induction, shadowed his father for a while, then got mentored by a bunch of senior executives, and was finally thrown into the deep end. “Figure it out and find your way. You need to experience wins and losses,” was the advice from his father who gave ample freedom to the newcomer to explore options, make mistakes, and learn. Ask him what is most impressive about the patriarch, and the son finds it hard to think of one aspect. But what definitely is worth emulating is RG’s big-picture approach. “His ability to think big, to look at a lot of things at the same time, and to think more long-term is unmatchable,” he avers. “He is far ahead in these areas,” says the son, adding that similarities are harder to spot than the differences. “He’s a big-picture guy. I might be better at micro-detailing and those kinds of things,” he says. The modest son doesn’t want to take credit for growing exports at a furious pace: From ₹2,631,2 crore in FY20 to ₹4,092.3 crore in FY24. “It’s always a team. It’s not me,” he says.

Another quick learning was that the entrepreneur was all by himself. The second-gen entrepreneur had an inornate induction, shadowed his father for a while, then got mentored by a bunch of senior executives, and was finally thrown into the deep end. “Figure it out and find your way. You need to experience wins and losses,” was the advice from his father who gave ample freedom to the newcomer to explore options, make mistakes, and learn. Ask him what is most impressive about the patriarch, and the son finds it hard to think of one aspect. But what definitely is worth emulating is RG’s big-picture approach. “His ability to think big, to look at a lot of things at the same time, and to think more long-term is unmatchable,” he avers. “He is far ahead in these areas,” says the son, adding that similarities are harder to spot than the differences. “He’s a big-picture guy. I might be better at micro-detailing and those kinds of things,” he says. The modest son doesn’t want to take credit for growing exports at a furious pace: From ₹2,631,2 crore in FY20 to ₹4,092.3 crore in FY24. “It’s always a team. It’s not me,” he says.

The second in the second-gen too prefers to keep a low profile. “My father built everything, my brother is now the driving force, and I am third in the pecking order,” says Neha Gupta Bector, who is married into the Bector family, which has a sizeable presence in exports, a handsome share in the QSR business in India, and a growing footprint in biscuits, cookies, and bread under the brands Cremica and English Oven. Mrs Bectors Food is the contract manufacturer of biscuits such as Oreo and Chocobakes for Mondelez, and exports biscuits to over 69 countries. “I was part of the group ever since I was 17 or 18, and got married when I was 24,” says the second-gen who takes care of the B2C side of the business for Trident. After working with her husband in the bakery division of Mrs Bectors for a few years, Neha realised that her heart would still yearn for yarn.

The second in the second-gen too prefers to keep a low profile. “My father built everything, my brother is now the driving force, and I am third in the pecking order,” says Neha Gupta Bector, who is married into the Bector family, which has a sizeable presence in exports, a handsome share in the QSR business in India, and a growing footprint in biscuits, cookies, and bread under the brands Cremica and English Oven. Mrs Bectors Food is the contract manufacturer of biscuits such as Oreo and Chocobakes for Mondelez, and exports biscuits to over 69 countries. “I was part of the group ever since I was 17 or 18, and got married when I was 24,” says the second-gen who takes care of the B2C side of the business for Trident. After working with her husband in the bakery division of Mrs Bectors for a few years, Neha realised that her heart would still yearn for yarn.

What also helped her gravitate back to textiles was the pandemic. Post-Covid, the home furnishing market witnessed a massive upswing. Seven years ago, towels were rolled out in the domestic market by default. “Whenever there was a cut in the export order, the towels used to get sold in the domestic market,” Gupta recalls. The response was encouraging. Soon, more items were added to the domestic cart: Bed sheets, bed covers, and pillows. The numbers, though, were still insignificant. Then came Covid, the demand exploded, and the tailwinds persisted. “Our online platforms are growing massively at about 40 percent,” claims Neha, chairperson of myTrident, a home furnishing brand started in 2014. In towels, Trident is the biggest brand on Myntra, and, in bedsheets, is among the top three on Amazon.

However, it’s quick commerce that has hit it out of the park. “In July, we sold about 15,000 sheets on Blinkit,” says Neha, who came back to myTrident in 2021. Over the last few years, the share of the B2C division to the overall revenue of Trident has inched to a high single-digit. “It’s still early days for us,” she adds. Stints at Trident and Mrs Bectors have helped her incorporate the best of both organisations. She explains: Mrs Bectors is unrivalled in softer skills like relationship building, is great at making diversification moves, has massive sales operations, and is a master at execution. “It’s a more bottomline-oriented organisation,” she adds. Trident, in contrast, has a performance-driven culture and is more about ‘risk-taking’. “It’s a more topline-oriented organisation,” she says. “Topline is in my blood, and the bottomline is something that I am learning,” she says with a smile.

Apart from the topline obsession, there is another thing she has inherited: A philosophical bent of mind. Ask her about success and failure, and one can see shades of RG in the second-gen. “If I feel good about myself and have respect for myself, then I am successful,” she says.

Now the challenge for the group is to diversify at a faster clip. A recent ratings report by CARE underlines the warning signs. “Trident is present in a cyclical, competitive, and fragmented industry,” notes the report released in April. Any adverse changes in the global economic outlook and demand-supply scenario in the domestic market directly impact the demand of players such as Trident. The group is also exposed to foreign exchange fluctuation risk and volatility in the prices of raw materials.

Now the challenge for the group is to diversify at a faster clip. A recent ratings report by CARE underlines the warning signs. “Trident is present in a cyclical, competitive, and fragmented industry,” notes the report released in April. Any adverse changes in the global economic outlook and demand-supply scenario in the domestic market directly impact the demand of players such as Trident. The group is also exposed to foreign exchange fluctuation risk and volatility in the prices of raw materials.

RG, for his part, prefers to look at the big picture. “Challenges will always be there. One needs to convert setbacks into opportunities,” he says. “One must try to succeed despite the odds,” adds the seasoned entrepreneur.

(This story appears in the 06 September, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)