The Karamchandanis of HyFun Foods: (from left) Haresh,MD & group CEO; Jayraj, director, Dhiraj, promoter; Kishanchand, director, Kamlesh, executive director

The Karamchandanis of HyFun Foods: (from left) Haresh,MD & group CEO; Jayraj, director, Dhiraj, promoter; Kishanchand, director, Kamlesh, executive director

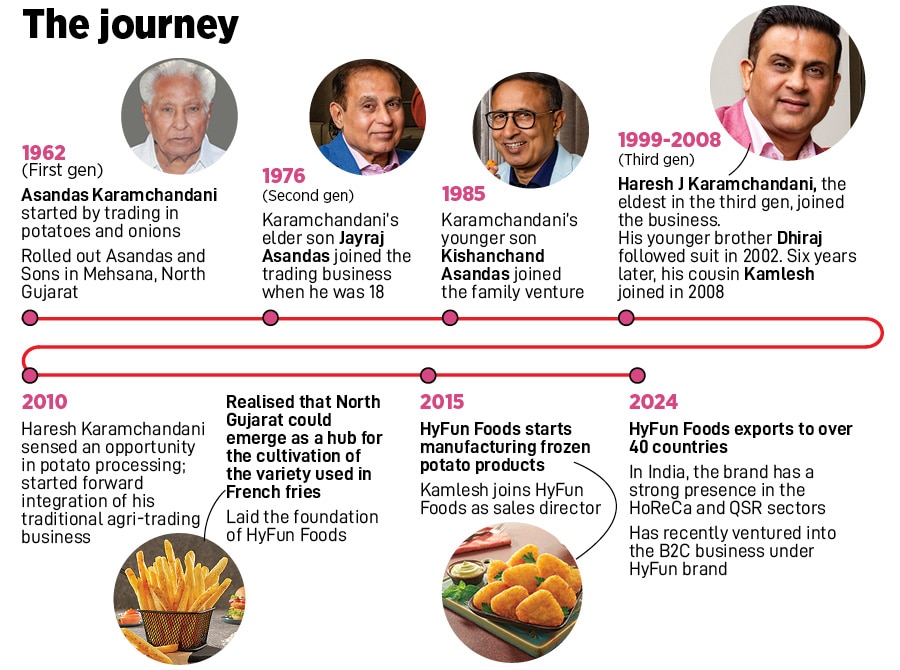

Ahmedabad, 2010 Haresh Karamchandani wore a smug smile. The third-generation entrepreneur, who joined the family business in 1999, was convinced that he had discovered the best way to slice a humble potato. “Higher the risk, higher the reward,” he told himself as he geared to take the boldest bet of his life and derive the most out of the ubiquitous vegetable. Towards the start of November, which marks the beginning of the potato season, the eldest in the third gen mustered the courage to discuss his ambitious plans with his family, which has been trading in potatoes since 1962. Back then, Asandas Karamchandani started trading in potatoes and onions from Mehsana, Gujarat. Over six decades later, in November 2020, his grandson was talking French. “Let’s make French fries,” he said flashing a broad grin.The proposal was not risky. It was hazardous.

The young Karamchandani wanted his family to diversify from trading in potatoes to processing frozen potato products. Aware that the topic would be a hot potato, he did his homework, explained that the risk-reward math was heavily loaded in favour of the new venture, and dished out wedges of reasons to buttress his case. First, the potato trading business was always hedged with limitations. And the biggest one was its curtailed scale. For decades, the family failed to expand the trading business to a meaningful proportion and sizeable impact. Now, HyFun—the new entity for the processed frozen potato venture—was an opportunity to scale aggressively.

Second, plain vanilla trading was nothing but a commodity business. Though there was money and volume, it lacked differentiation. There were thousands of such traders across the country. The same profession, the same outcome. Third, Karamchandani wanted to add value. He wanted to upgrade the family business. While the first generation builds and the second generation adds, the subsequent generation needs to multiply. The only way to multiply, he underlined, was to enter the familiar territory of potatoes and produce something distinct that could be sold across the country and outside India. Till 2011, India used to import French fries. “There is a big opportunity to flip the equation,” he urged, underlining the natural advantages that the family had in getting into the business of frozen potato products: Location, geography and the know-how in potato cultivation. The bet indeed looked rewarding.

The family, however, was more worried about the risk. For decades, it only knew, and mastered, one thing: Trading in potatoes. Now, the next gen was nudging it towards manufacturing, which was an alien territory. The absence of technical know-how notwithstanding, there were other red flags as well. First, the frozen potato segment had a Goliath in McCain. The Canadian player had built a robust manufacturing, distribution and retail footprint in institutional businesses and consumer space. “How can a rookie take on the giant?” was the logical question hurled at the maverick entrepreneur.

Second, the family had spotted a bunch of rotten potatoes. At least five players had tried their luck in the frozen potato space by setting up plants across Punjab, Coimbatore, Agra and Jabalpur. All had failed. Karamchandani offered a logical explanation. “All sprung up at the wrong locations. That’s why they couldn’t source potatoes of the best quality,” he underlined. “We have positives in our favour,” he maintained and won the family’s backing. “We are taking a calculated risk,” he underlined.

A year later, in 2011, the ‘calculated risk’ exploded. Karamchandani explains what went wrong. Among the major suppliers of frozen potato processing equipment globally, the young entrepreneur zeroed in on a vendor in the Netherlands. He completed a detailed due diligence, made an advance payment of `2.25 crore, and started building a factory for the tools, which were scheduled to be delivered within a year. Six months later, the company went bankrupt. Karamchandani was devastated.

What was most damaging, though, was a dent in the confidence expressed by the family for the yet-to-be-born venture. “It was the family money,” recalls Karamchandani. “It was a huge setback,” he adds. The misfortune opened a can of worms. From being construed as ‘bad omen’ to being told that it’s a ‘divine message’ to shun the new plan, the embattled entrepreneur found himself on a sticky wicket. Well, it seemed like Karamchandani would end up a few fries short of a ‘happy meal’.

The debacle also blighted the morale of the hustler. Karamchandani joined the family business in 1999, and six years later dawned a realisation that he was the odd sack in the family. “My grandfather never wanted me to join the trading business,” he recounts. His father too encouraged the young lad to lead an independent life. “Quite early in life, I was sent to a boarding school in Mount Abu in Rajasthan,” he says. His college years were also spent away from the family and the business in Ahmedabad. In 2005, Karamchandani started exploring different options. From flirting with the idea of rolling out a multiplex theatre chain in Gandhinagar to trifling with the idea of starting something in tourism to lunging for a Maruti dealership, multiple courses of action were examined. None materialised.

A few years later, the frozen potato business emerged as the best bet in 2010. But a year later, the bankruptcy news came as a massive setback for the entrepreneur. Karamchandani, though, didn’t give up. He remained in touch with the Dutch government and the Indian embassy, and finally, there was respite. A new entity took over the bankrupt company, the commitment was honoured, and the equipment landed in Gujarat after a delay of close to two years.

A delayed start punctuated the production plan, which now commenced in 2015. And this triggered the second big problem. “We planned to start manufacturing in July, but it kicked off in the first week of December,” recalls Karamchandani, adding that he got his timing wrong. Reason? Potato is harvested in February and March, and is sowed until December, a month when the industry stops production because of the rough quality of the crop. “Imagine, we started production in December and launched the product in the market,” he says, adding that the quality took a hit. “It was a blunder,” he confesses.

A delayed start punctuated the production plan, which now commenced in 2015. And this triggered the second big problem. “We planned to start manufacturing in July, but it kicked off in the first week of December,” recalls Karamchandani, adding that he got his timing wrong. Reason? Potato is harvested in February and March, and is sowed until December, a month when the industry stops production because of the rough quality of the crop. “Imagine, we started production in December and launched the product in the market,” he says, adding that the quality took a hit. “It was a blunder,” he confesses.There was quick learning but there was one more stumbling block. Karamchandani started scouting for export opportunities towards the fag end of 2016 and bagged his first order from Thailand. “The first export consignment was a big disaster for us,” he recalls. Around 50 percent of the shipped orders were rejected by the supermarket chain. This time, though, the fault lay with the importer. Karamchandani explains. There were a bunch of technical product specifications which were not communicated by the importer. “He (the importer) was a rice trader and didn’t have any knowledge about frozen potato products,” he points out.

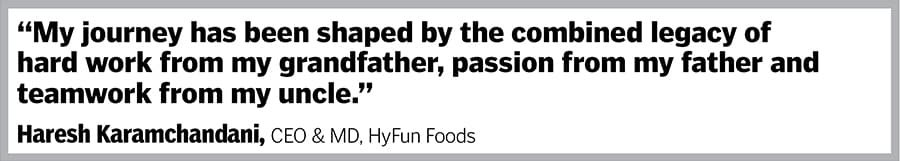

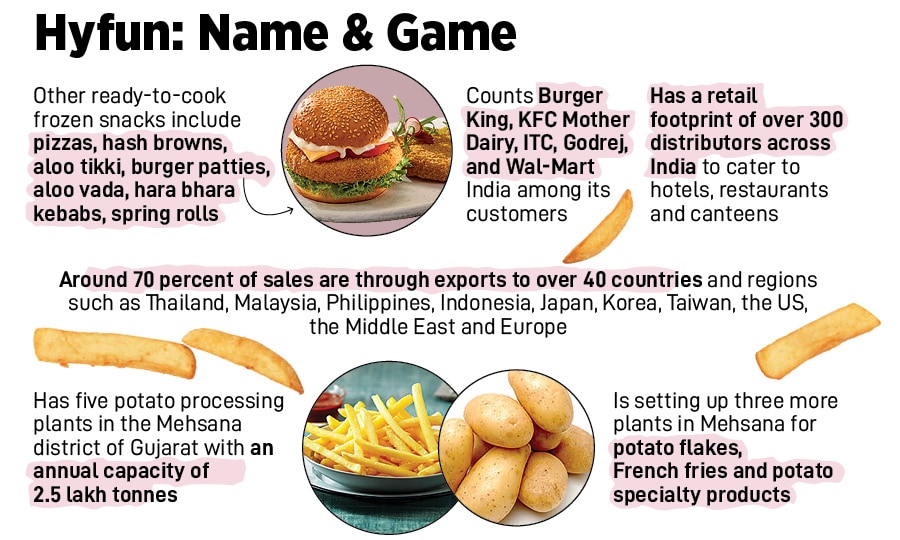

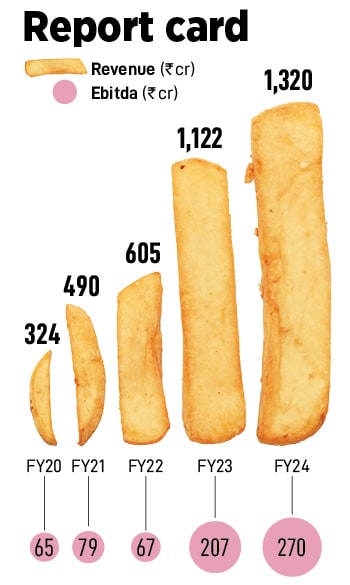

Fast forward to August 2024. HyFun has taken pole position in the production of frozen potato products in India. “We are the biggest exporter of frozen French fries,” claims Karamchandani, chief executive officer and managing director of HyFun Foods. The company, he underlines, has grown at a brisk pace. Take, for instance, revenue, which has leapfrogged from `324 crore in FY20 to `1,320 crore in FY24. Ebitda (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) during the same period has jumped from `65 crore to `270 crore.

Fast forward to August 2024. HyFun has taken pole position in the production of frozen potato products in India. “We are the biggest exporter of frozen French fries,” claims Karamchandani, chief executive officer and managing director of HyFun Foods. The company, he underlines, has grown at a brisk pace. Take, for instance, revenue, which has leapfrogged from `324 crore in FY20 to `1,320 crore in FY24. Ebitda (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) during the same period has jumped from `65 crore to `270 crore.Exports, interestingly, have fuelled growth. While around 70 percent of sales are through exports to over 40 countries and regions such as Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, the US, the Middle East and Europe, in India, it counts Burger King, Burger Singh, KFC, Mother Dairy, ITC, Godrej and Walmart India among its long list of customers. The family too has joined the young turk in his audacious journey. In 2015, Karamchandani’s younger brother joined HyFun Foods as sales director. “He has been instrumental in driving exports,” says Karamchandani.

The transformation of the traditional family business gets a thumbs-up from the patriarch. “I am incredibly proud of my son Haresh for his visionary leadership in building HyFun Foods into a global brand,” says Jayraj Karamchandani, director of HyFun Foods. Ask him how he looks at the restless young breed of the next gen driving the family businesses and the seasoned founder maintains that one must keep the context in mind before passing a judgement. “The landscape today is drastically different from when I started,” says the second-generation entrepreneur who joined the family business in 1976. “Back then I was just 18,” he says, adding that entrepreneurs now benefit from instant access to information and a global network of opportunities, enabling them to dream big and grow fast. “This has given today’s generation a broader vision,” he adds.

Despite changes in the business environment over the last decades, a few things remain constant for every generation. The senior Karamchandani explains. “While the tools and resources have advanced, the essence of what it takes to succeed has not changed,” he maintains. Hard work, perseverance and dedication are still the foundation for success. “It’s this continuity of values that ensures progress across generations,” he adds.

Despite changes in the business environment over the last decades, a few things remain constant for every generation. The senior Karamchandani explains. “While the tools and resources have advanced, the essence of what it takes to succeed has not changed,” he maintains. Hard work, perseverance and dedication are still the foundation for success. “It’s this continuity of values that ensures progress across generations,” he adds.Industry observers underline the undiminishing role of family-owned businesses (FOBs). “In India, FOBs contribute more than 75 percent of national GDP, one of the highest percentages in the world,” pointed out the latest study by McKinsey in August. The number is likely to rise to 80 to 85 percent by 2047, contends the note titled ‘Five differentiators of outperforming family-owned businesses in India’.

Between 2017 and 2022, FOBs reported around 2.3 percent higher revenue growth than businesses not owned by families. “Between 2012 and 2022, FOBs’ returns to shareholders were twice as high as those of non-FOBs,” says the McKinsey study by Avinash Goyal, Chaitali Mukherjee, Rohit Tanwar and Vardhan Patankar. “If FOBs are to continue to power growth—both their own and that of the wider economy—it is imperative for them now to be bold,” the study added.

The next gen in family businesses, point out marketing experts and analysts, are taking bold steps by shunning a blinkered approach. “Haresh Karamchandani could have added to the traditional business but he opted to diversify,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor of marketing at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. While charting a new path is courageous, entering an unknown territory—frozen French fries and potato products—and taking on the big guys like McCain need a lot of character and chutzpah. Though he started with exports—a low-hanging fruit to boost the top line and bottom line—the audacity to roll out the brand in the domestic consumer market shows the entrepreneur’s long-term vision.

The next gen in family businesses, point out marketing experts and analysts, are taking bold steps by shunning a blinkered approach. “Haresh Karamchandani could have added to the traditional business but he opted to diversify,” says Ashita Aggarwal, professor of marketing at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. While charting a new path is courageous, entering an unknown territory—frozen French fries and potato products—and taking on the big guys like McCain need a lot of character and chutzpah. Though he started with exports—a low-hanging fruit to boost the top line and bottom line—the audacity to roll out the brand in the domestic consumer market shows the entrepreneur’s long-term vision.Karamchandani, for his part, is bullish on transforming HyFun as a full-stack frozen food brand. “We are going beyond potatoes,” he says, adding that the Indian consumers need variety. He shares a long list of products in his armoury: Frozen pizzas, gravies, samosas, paratha, momos and spring rolls. But is he not spreading HyFun too wide by taking it into multiple categories within frozen foods? Karamchandani says with a smile: “Higher the risk, higher the reward.”