Poignancy is not a word we associate with surrealism, but you feel it when you walk down a corridor of blown-up photobooth pictures and enter the Pompidou’s blockbuster marking the movement’s 100th birthday. Everybody was so young when the first surrealist manifesto was published in October 1924: was it really a century ago? Painter Yves Tanguy sports a punk hairstyle as he grimaces for the automatic camera; Marie-Berthe Aurenche, another painter, whips her hair up into chaos; Salvador Dalí closes his eyes as if asleep.

These people are funny and having fun. Of all the modernist art movements, it was the surrealists who were best at enjoying their revolution. In the Pompidou’s perfectly judged exhibition, that pleasure shines through as you meet these artists, all dead now, not so much as giants of art history as extremely amusing companions.

To access that immersive tunnel of portraits, you pass though the maw of a monster. Like the show’s spiralling structure, this is modelled on classic surrealist exhibitions devised by Marcel Duchamp, luring you in to lose yourself in reveries. Within this coiled structure, the Pompidou’s show has little chronological pedantry. Dorothea Tanning’s 1970 installation Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot, of a Paris hotel room invaded by naked ghosts, rubs shoulders with Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings from the eve of the first world war, retrospectively hailed as surrealist by the 1924 manifesto.

Linear time is one of the mundane realities the surrealists scorned. In De Chirico’s Premonitory Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire, painted in early 1914, the poet Apollinaire has a target on his head. Apollinaire would indeed get a fatal head wound in the first world war. De Chirico claimed to have foreseen it in this painting and the surrealists believed him. It also features a classical bust wearing glasses. And a jelly mould of a fish.

Although the surrealists admired Freud, they were not scientifically “Freudian”. They were fascinated by hauntings, visions, the inexplicable. The author of the 1924 manifesto, André Breton, was a poet and so were his fellow founders such as Paul Éluard and Robert Desnos: their “researches” into dreams and automatic writing attempted to unlock the wellsprings of poetic inspiration. Surrealist art, too, as we see here, releases images that are pure poetry: the artist doesn’t understand and can’t explain where they come from.

Any rationalisation Dora Maar might have offered for her 1934 photograph of a woman’s hand emerging from a sea shell would have been a redundancy. So would any interpretation Max Ernst might have given of his collage novel La Femme 100 têtes, with its confounding mysterious conjunctions of cut-up Victorian engravings.

What sweeps you along, laughing and marvelling, is the joy and liberation the artists felt making their art, or rather letting it be made by forces unknown. Once you signed up as a surrealist and adopted the movement’s methods, art slipped out unbidden. Exquisite corpse drawings here, made as a game by surrealist gatherings that included Breton, Jacqueline Lamba and more, are monuments to good times in Left Bank cafes. From Ernst’s wax rubbings to Man Ray’s Rayogrammes created by putting objects on to sensitive paper, surrealists found magic techniques to unlock the unconscious.

Surrealist art is literally irresponsible. The artist hands over creativity to the psyche and whatever comes will come. That makes it magnificently dirty. Desires are unleashed without any internal censor. You dreamed of floating engorged cocks while sleeping on your chaise longue? Draw it, darling, as the Czech artist Toyen did in 1930, titling it Sans titre (rêve de jeune fille). But of course no surrealist was more graphic about his depraved fantasies than Dalí. His 1929 painting The Great Masturbator is also in the exhibition’s naughty room, along with his Scatological Object Functioning Symbolically, a tribute to shoe fetishism and Gala. Or Gala’s shoes I suppose.

Dalí even disgusted the surrealists by dreaming of Hitler, mocking Lenin and getting rich in America – his dream sequence from Hitchcock’s Spellbound is projected here. He has appalled critics since, but his defiant bad taste is deliriously ageless. If you doubt his genius, look at his 1931 painting The Dream – a green-hued woman materialising in shadows, her hair flowing like water, ants swarming over her face.

This show makes surrealism look easy and gathers the many people who took up its revolutionary hedonism. Yet the real mystery uncovered is how an art movement that didn’t take itself seriously and has often been dismissed as modernism lite engendered such masterpieces.

after newsletter promotion

You could look for years at René Magritte’s 1938 canvas Time Transfixed – but I don’t recommend it, as you start to doubt reality very fast. A tiny steam train emerges from an ordinary fireplace in an ordinary room, yet the train suspended in mid-air is the least of the painting’s uneasy elements. You are left wondering which is more absurd, a train flying in from nowhere or the objects and routines with which we reassure ourselves such things can’t happen.

Another extraordinary Magritte, Ideas of the Acrobat, which distorts, remakes, mixes and matches the body, hangs next to Picasso’s diabolical flirtation with surrealism, his 1929 A Blue Acrobat. It’s a dazzling juxtaposition of geniuses. Picasso’s impossibly contorted, mutant human creature is monstrous, heroic and absolutely real, because his grasp of human form is so innate.

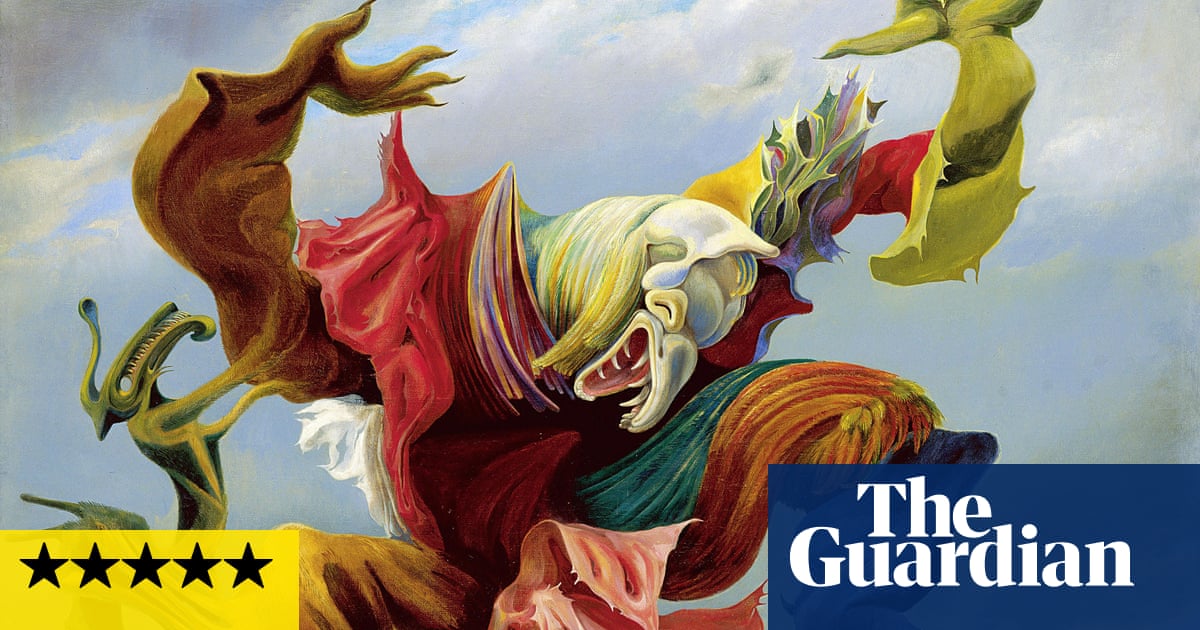

In 1937, Ernst, too, painted a sprawling, stomping monster he called Fireside Angel (The Triumph of Surrealism). He said it was about the rise of fascism and you feel that with a chill. But what does the subtitle mean? Ernst, who saw himself as shaman and seer, foretells here that the surrealist movement’s most enduring legacy would be the word “surreal” itself and how it’s used not just to suggest the funny but the strange and out-of-joint. So in a horrible way, fascism is surreal. So are many things happening a century on. Surreal times then and now.