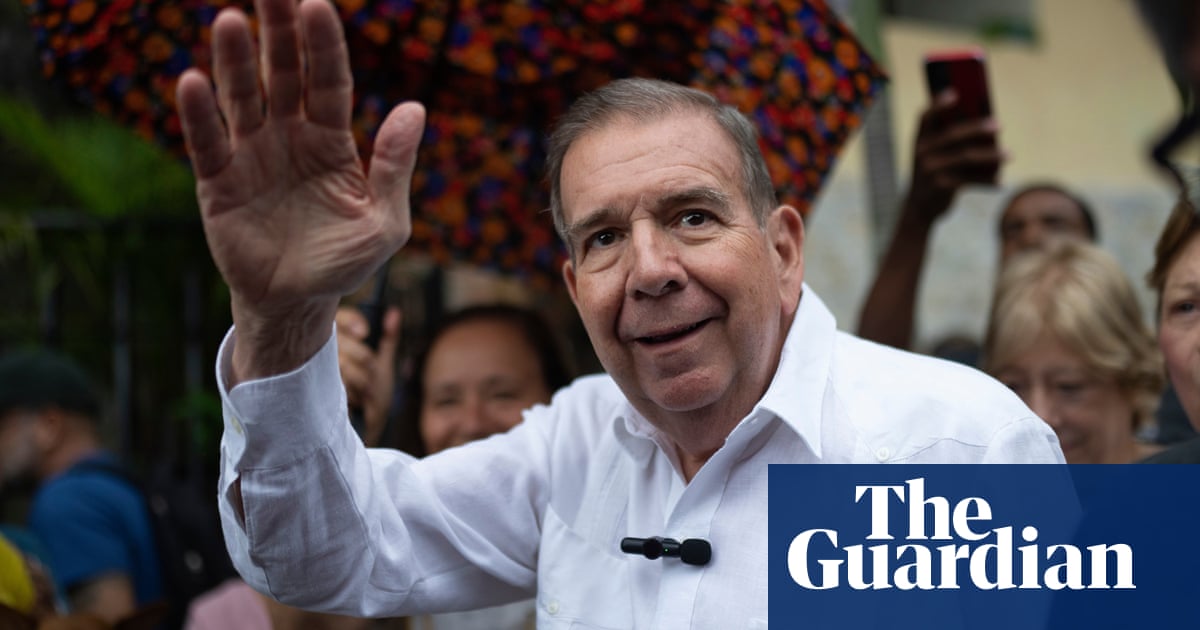

The Venezuelan opposition leader and former presidential candidate, Edmundo González, has gone into exile in Spain, dealing a bitter blow to opponents of the country’s authoritarian president, Nicolás Maduro.

Early on Sunday, Spain’s foreign minister, José Manuel Albares, announced González was on his way to Spain having boarded a Spanish air force plane in Caracas.

“He has … requested asylum and the Spanish government will of course process this and concede it,” Albares told the Spanish public broadcaster RTVE.

“I have been able to speak to [González] and once he was aboard the airplane he expressed his gratitude toward the Spanish government and Spain,” he added.

“Of course I told him we were pleased that he is well and on his way to Spain, and I reiterated the commitment of our government to the political rights of all Venezuelans.”

González, a 75-year-old retired diplomat, went to ground in the days after Venezuela’s 28 July election, which detailed voting data published by the opposition suggests he won. But Maduro has claimed victory and in early September a warrant for González’s arrest was issued for alleged crimes that could have seen him spent the rest of his life in prison.

Venezuela’s vice-president, Delcy Rodríguez, said González, who several foreign governmentshave announced as the legitimate winner of the ballot, had left after “voluntarily seeking refuge” in the Spanish embassy. She claimed granting him safe passage out of the country was designed to “contribute to political peace”.

González had been in hiding for a month but his situation became particularly uncomfortable in recent days after he was accused of a series of crimes including criminal association, which carries a prison sentence of up to 10 years, and conspiracy, which can be punished with a 16-year sentence.

Maduro’s recent decision to make Diosdado Cabello, one of his political movement’s most hard-line figures, interior minister also heightened concerns. Maduro’s administration has accused González and his key backer, the prominent opposition leader María Corina Machado, of being part of a US-backed “fascist” counter-revolution targeting their Chavista regime.

Cabello has repeatedly called González – who friends and acquaintances describe as a softly spoken public servant and grandfather – a coup-mongering “rat”.

Joel García, a lawyer who has defended several opposition figures in Venezuela, said that if González was charged with everything the government has accused him of, he could face a jail sentence of 30 years.

Speaking at a socialist party meeting on Saturday, Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, had described the opposition leader as “a hero who Spain will not abandon”.

Venezuela has been in political crisis since authorities declared Maduro the winner of the 28 July vote with a score of 52%. However, tally sheets collected by volunteers from more than two-thirds of electronic voting machines and published online indicate González won by a more than 2-to-1 margin.

Venezuela’s top court – which is controlled by Maduro’s allies – has confirmed his supposed victory but numerous countries and bodies, including the US, EU and several Latin American nations, have refused to recognise Maduro’s re-election for a third six-year term unless Caracas releases full voting data.

Opposition hopes that their apparent electoral success might translate into a peaceful transition of power evaporated in the days after the vote. Two days of street demonstrations were extinguished by a harsh government crackdown nicknamed Operación Tun Tun (Operation Knock Knock).

Human rights groups say more than 1,700 people have been detained, including more than 100 teenagers and several key opposition figures who were captured by secret police. Six other important opposition figures are holed up at Argentina’s embassy in Caracas, which is in the custody of Brazil because Maduro has cut ties with Buenos Aires. In recent days the embassy compound has been surrounded by police and intelligence agents and had its electricity cut.

Previously unknown to most Venezuelans, González – a last minute stand in after Machado was banned from running – ignited the hopes of millions desperate for change after a decade of economic freefall that has seen GDP drop 80% and more than 7 million people emigrate.

Speaking at his apartment in Caracas shortly before the election, the former ambassador vowed to build “a prosperous, democratic and peaceful country … a country of and for everyone”.

News of González’s departure prompted an outpouring of frustration and distress on Sunday among opposition supporters and members of the international community.

“Today is a sad day for democracy in Venezuela … In a democracy, no political leader should be forced to seek asylum in another country,” the EU’s foreign policy chief Josep Borrell said in a statement.

Borrell said González – who EU states believed had won the recent election “by a large majority” – had been taken in at the Dutch ambassador’s residence in Caracas last Thursday. His request for political asylum was a result of “repression, political persecution, and direct threats to his safety and freedom”.

In an article simply entitled, ‘Edmundo Left’, the Venezuela-focused website Caracas Chronicles painted a bleak outlook for the opposition.

“We’ve witnessed in the past how the remote-controlled or holographic opposition leadership quickly deflates [in exile],” it said, arguing that the arrest warrant issued against González had been purposely designed to force him to flee.

“Maduro never had the intention of arresting González … They could have apprehended him at any moment, the expected outcome was to make him leave,” Caracas Chronicle argued, noting how his exit contradicted the opposition campaign’s “mantra” that it would fight “until the end”.

With González gone, “a nation turns its lonely eyes to one person: María Corina Machado,” the website concluded.

There is no immediate sign that Machado will follow her colleague’s footsteps into exile.

Asked by the Guardian on Thursday if she planned to abandon her country, the 56-year-old conservative was categorical, replying: “I believe my duty is to stay in Venezuela.”

However, Machado admitted that every day it became “harder and riskier” to stay in Venezuela given the “dangerous times” it was living through.

The Chavista era began a quarter of a century ago after the 1998 election of Maduro’s mentor, Hugo Chávez. The former military officer vowed to use Venezuela’s vast oil reserves to bankroll a social “revolution” in a country that remained profoundly unequal despite being long considered “South America’s Saudi Arabia”. But the collapse of oil prices after Chávez’s premature 2013 death – and his government’s failure to prepare for such an eventuality – plunged Venezuela into a historic depression that was compounded by harsh US sanctions.

Venezuela’s economic collapse caused one of the largest migration crises in Latin American history with about 8 million citizens moving abroad. It also produced a succession of challenges to Maduro’s increasingly authoritarian rule, including mass protests, a 2018 assassination attempt, the recognition of “parallel president” Juan Guaidó in 2019 and the recent election. He has survived them all, thanks to political repression, the continued support of the armed forces, and the backing of China and Russia.