Getty Images

Getty ImagesA scheme allowing the early release of thousands of prisoners in England and Wales comes into effect on Tuesday.

About 1,700 are expected to be freed on the first day, with a total of about 5,500 to leave prison early during September and October.

The emergency measure is aimed at dealing with prison overcrowding and the risk of jails running out of space.

Which prisoners will be released?

Eligible prisoners who have served only 40% of their fixed term sentence, rather than 50%, will be automatically released.

Those who are in jail for serious violent offences with sentences of four years or more, as well as sex offenders, will not be included.

It will also exclude those convicted of domestic abuse and what the government calls “connected crimes”, such as stalking and controlling or coercive behaviours.

The scheme also only applies to a certain type of prison sentence, under which prisoners are automatically released after a set amount of time.

More serious offenders serving life sentences, for example, are only released after the Parole Board has assessed whether they still pose a risk.

Anyone released will be monitored by the Probation Service and this could involve the use of electronic tagging and curfews.

How many people are in prison?

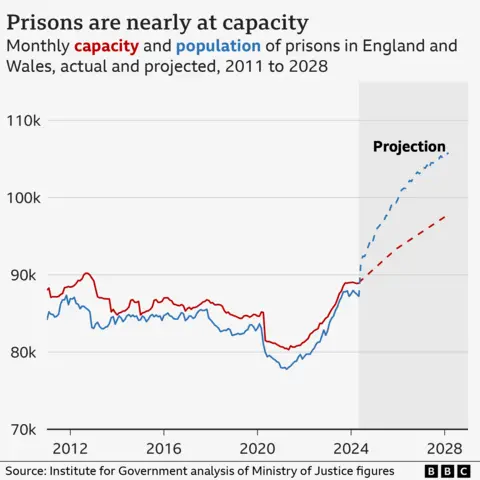

Ministry of Justice data shows the total England and Wales prison population on 6 September was a record high of 88,521.

And the “usable operational capacity” – the total number of people a prison can hold while taking into account issues like control and security – was 89,619, leaving spare capacity of just 1,098 places.

This is well above the prison service’s own measure of a “good, decent standard of accommodation”, which was 79,856 at the end of July.

Pressure on the system has been added in recent weeks by the jailing of people involved in the summer’s rioting.

Approximately 250 people had been jailed for offences relating to those riots as of the end last week.

At current rates, the prison population is projected to rise by about 17,000 by 2028, while capacity is set to rise by 9,000.

The early release of inmates, to ease pressure on prisons, also happened under the Conservatives and under the last Labour government.

Prisons in Scotland have also had to release people early to ease overcrowding. There were more than 8,000 people in prison in Scotland last week.

Last year, prisons in Northern Ireland had an average daily population of 1,685, a figure which has risen in recent years.

In 2018 – the latest year for which comparable data is available – England and Wales had 150 prisoners per 100,000 people, the highest proportion in Western Europe.

Spain (138 per 100,000) and Portugal (126 per 100,000) were the two western European countries with the next highest rates of imprisonment.

Why have prisons become so full?

The Institute for Government think tank says part of the answer is longer sentences.

In 2023, the average prison sentence given in the Crown Courts in England and Wales, which deal with more serious offences, was more than 25% longer than in 2012.

For some crimes, the increase has been even greater. Sentences for robbery, for example, were 13 months longer on average in 2023 than in 2012, a rise of 36%.

Longer sentences mean more people in prison at any given time.

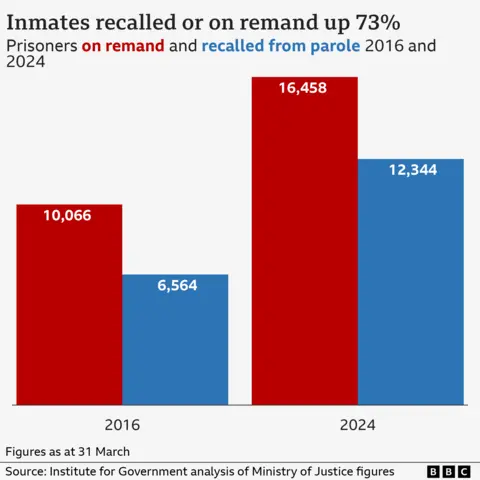

Another part of the answer is the increase in prisoners on remand, who are waiting for their trial to start, or to be sentenced.

In March this year the remand prison population stood at 16,458, a record high. In 2016, it was about 10,000.

Some of this increase has been driven by a record number of Crown Court cases waiting to be heard.

More people than before are also being returned to prison for breaching their release conditions.

In March, the number was around 12,000 – another record high – and roughly double the number in 2016.

Why not build more prisons?

In its 2021 spending review the then Conservative government said it would build an extra 20,000 prison places in England and Wales “by the mid-2020s”.

But only about 6,000 have been built to date.

The chief civil servant in the Ministry of Justice wrote in July last year that only £1.1bn of the £4bn committed to this prison building programme had been spent.

One of the obstacles to hitting the construction target has been the planning system and local objections to new prisons, including from some Conservative MPs.

And building more prisons is expensive. The former justice secretary Alex Chalk told the BBC Today podcast in July that the cost of every new cell was around £600,000. However, no official estimates of such construction costs are available.

How will Labour tackle the prisons problem?

In July, the new Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood told Parliament she will publish a new “10-year capacity strategy” later this year, to “acquire new land” for prison sites.

She also suggested prison building would be “placed in a minister’s hands” – a hint that decisions on building new prisons could be taken away from local planning authorities.

Yet there are also signs Labour might take a different approach.

Before he was appointed the new prisons minister, James Timpson, in a Channel 4 interview, said he wanted to break the cycle of re-offending by giving ex-offenders more job opportunities.

That is something he has done through his family firm Timpson. The key cutting and shoe-repair company says around a tenth of its employees are former prisoners.

Mr Timpson also spoke about reducing sentencing and sending considerably fewer people to prison than we currently do.

“So many of the people in prison in my view shouldn’t be there. A lot should but a lot shouldn’t, and they’re there for far too long” he said.

The Conservatives’ Neil O’Brien is among critics of the plan and has argued that “prison works”.