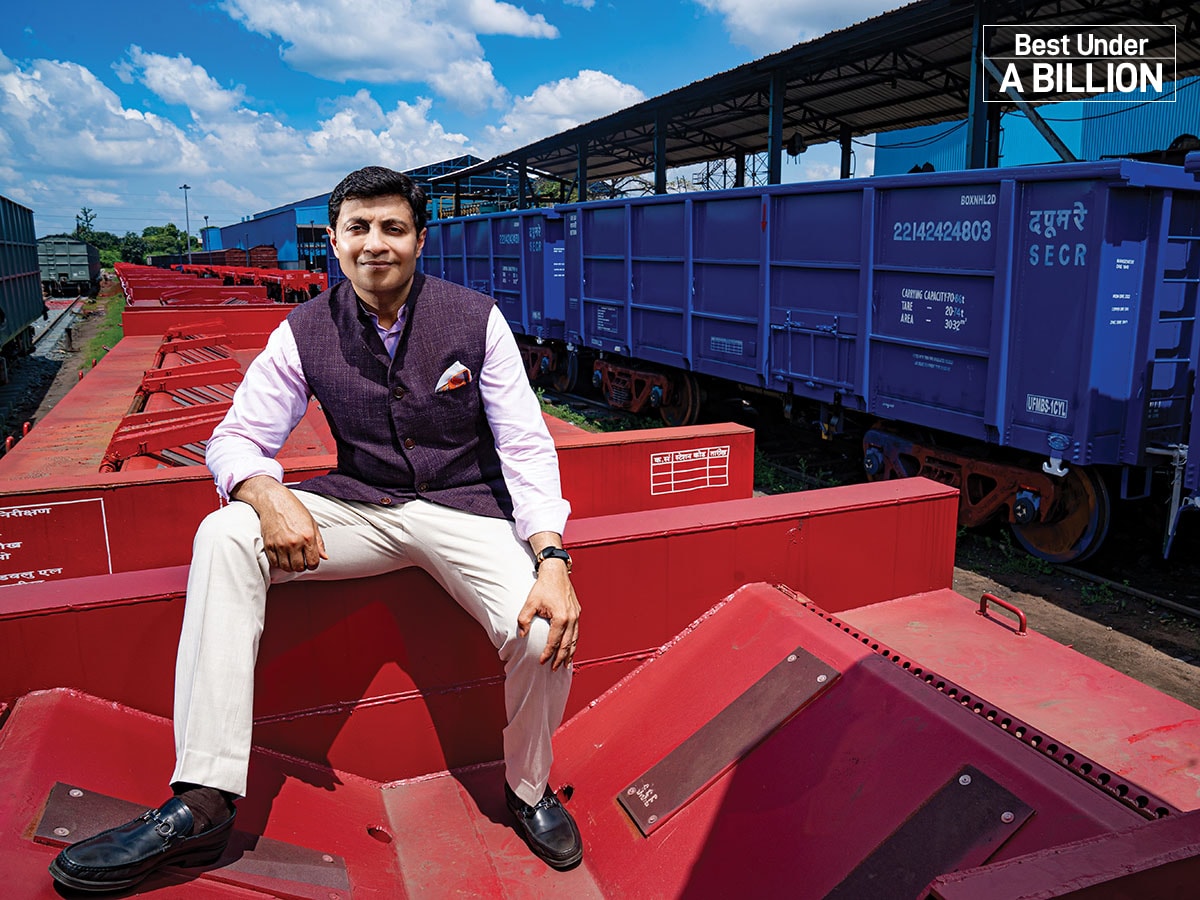

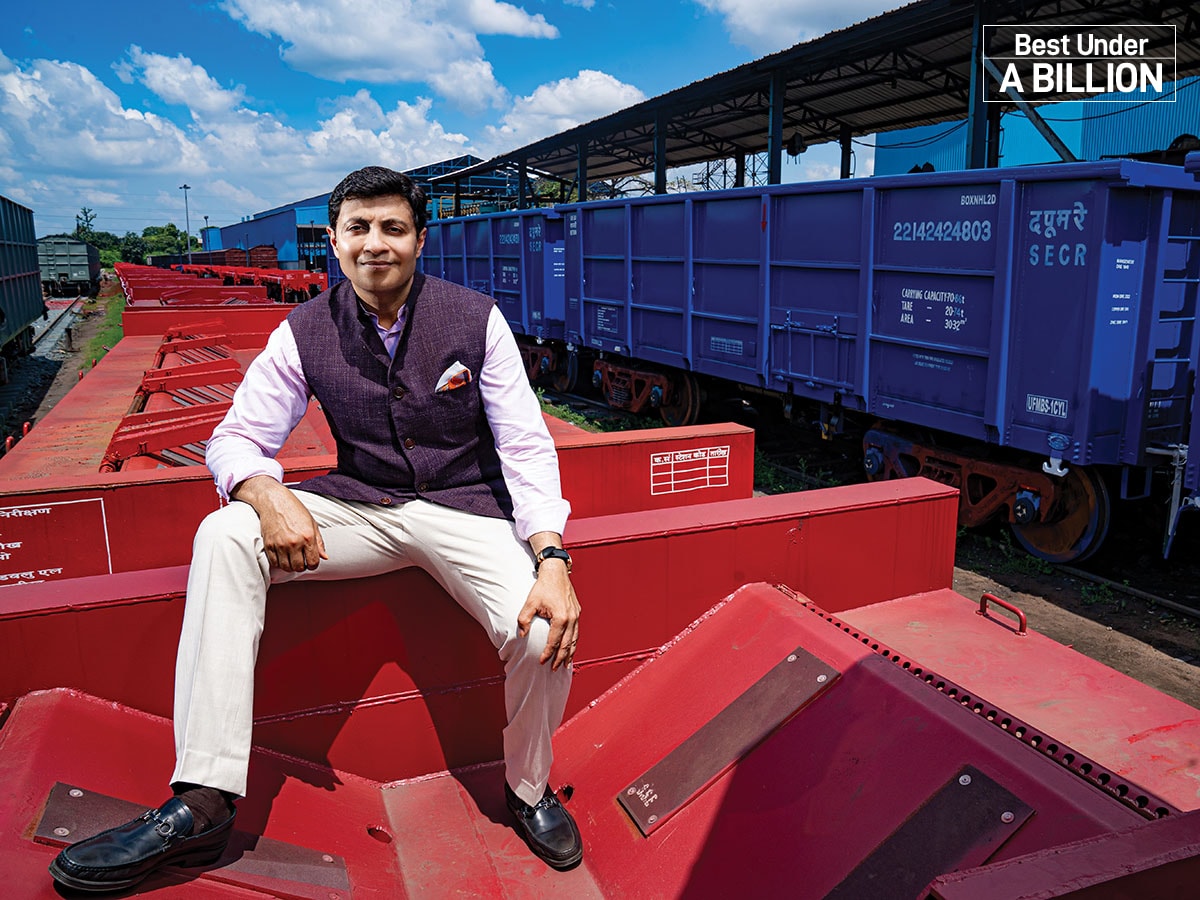

Vivek Lohia, Managing director, Jupiter Wagons Limited. Image: Mexy Xavier

Vivek Lohia, Managing director, Jupiter Wagons Limited. Image: Mexy Xavier

For most of his life, Vivek Lohia’s father had worked in executive roles at the now-defunct Kolkata-based Hindustan Development Corporation (HDC), a maker of railway products, before Vivek, his Wharton Business School-educated son, nudged him to set up their own entrepreneurial venture. Growing up in Kolkata, junior Lohia’s conversations with his father often revolved around wagons and trains.

“They (HDC) were one of the pioneers in the railway sector. He [Vivek’s father] had helped set up that company,” says Lohia. “The whole idea was that since we have so much of knowledge about the sector and relationships—not only with the companies on the private side but also with the government—we felt it was a good opportunity… that is how we made our foray into the sector.”

Lohia had come back from the US after working there for a few years, and along with his father, set up Jupiter Wagons Limited in 2006 to help build wagons, mostly for the Indian Railways. “Back then, there were only two or three companies dominating the sector,” Lohia says. “Since we had so much in-depth knowledge of the sector, we knew that there was a lot of complacency in the way they did business.”

Jupiter Wagons started by setting up a foundry in Kolkata where it made castings, couplers and draft gears for railway wagons before going on to build freight cars and wagons. The company’s first customer was the Indian Railways, and it made boxing wagons to carry coal and iron ore for the 171-year-old public sector organisation.

Since then, the Kolkata-headquartered company has grown into one of India’s largest railway engineering behemoths with a market capitalisation of Rs24,000 crore. The company’s annual revenues stand at Rs3,641 crore as of March 2024, with profits of Rs332.8 crore. That number is likely to swell to Rs10,000 crore in the next three years, with a bottom line of Rs1,000 crore, if plans set by the Lohias fructify.

“Over the years, Jupiter Wagons Limited (JWL) has gained significant experience and has established strong relationships with the government and private customers in iron and steel, power, logistics, mining, cement sectors, and other reputed OEMs, resulting in steady order inflow,” ratings agency, Crisil said in February. “Technology tie-ups and partnerships with global entities have strengthened JWLs technical know-how and capabilities. This has resulted in a wide product portfolio and diversification from the core wagon manufacturing business.”

Today, Jupiter Wagons has also diversified into making electric vehicles (EV), with a one-tonne commercial EV expected in the next few years in addition to manufacturing containers used to house data centres and wheel sets and brakes for the railway sector, especially Metro and Vande Bharat coaches. The company is also a maker of bodies for tipper lorries and tankers, in addition to crossings for railways.

“From the very beginning, our focus was on integration,” says Lohia, managing director of Jupiter Wagons. “We were also looking to innovate and bring in new technology, even though, with the railways, designs were fixed. But I knew that, in the long term, technology will always help you grow.” Also read: Indian companies should focus on high value manufacturing: Vijay Govindarajan

Going Steady

Still, in many ways, Jupiter Wagons’ change in fortunes came almost a decade [in 2015] after it set up operations.

That year, the company struck a deal with Slovakian rail maker Tatravagonka Poprad to sell a 26 percent stake in the company. By then, Jupiter had expanded its manufacturing to passenger coaches and railway turnouts, in addition to wagons and wagon components. A turnout is a track configuration that enables trains to move from one track to another. Jupiter’s disc brake manufacturing plant at Jabalpur. Image: Mexy Xavier“They were looking to partner with somebody who was vibrant, who had energy and the will to grow,” says Lohia. Tatravagonka, which counts itself among the largest freight car makers in Europe, bought the stake in Jupiter for Rs90 crore, valuing the company at a little over Rs300 crore. In Europe, Tatravagonka has a 40 percent market share and produces close to 5,000 freight cars with revenues of around € 600 million. The company also employs over 2,300 people and, apart from rail freight cars and bogies, it also undertakes repair and maintenance of railway vehicles.

Jupiter’s disc brake manufacturing plant at Jabalpur. Image: Mexy Xavier“They were looking to partner with somebody who was vibrant, who had energy and the will to grow,” says Lohia. Tatravagonka, which counts itself among the largest freight car makers in Europe, bought the stake in Jupiter for Rs90 crore, valuing the company at a little over Rs300 crore. In Europe, Tatravagonka has a 40 percent market share and produces close to 5,000 freight cars with revenues of around € 600 million. The company also employs over 2,300 people and, apart from rail freight cars and bogies, it also undertakes repair and maintenance of railway vehicles.

“I think that was a huge game changer for us,” Lohia says. “We got the much-needed capital and access to a lot of technology. Tatravagonka had a strong network in Europe, and we could form other joint ventures and enter into technology-related products like the brake systems.” The partnership with Tatravagonka soon led Jupiter Wagons to form relations with other Czech Republic-based companies such as Dako and Kovis. “We also learnt about how to design new cars because till then in India, the design or the R&D was small as the railways used to own most of the wagons,” Lohia says. Today, Jupiter Wagons has two separate joint ventures with Kovis and Dako for manufacturing brake discs. The company claims to be the biggest supplier of brakes to the Indian Railways for the passenger coaches, for the Vande Bharat trains and it is also exporting them to the European market.

Today, Jupiter Wagons has two separate joint ventures with Kovis and Dako for manufacturing brake discs. The company claims to be the biggest supplier of brakes to the Indian Railways for the passenger coaches, for the Vande Bharat trains and it is also exporting them to the European market.

With Dako, the joint venture manufactures brake systems for high-speed passenger trains, metro coaches, and freight cars, in addition to axle-mounted disc brakes, bogie-mounted brakes, and wheel slide protection. With Kovis, the company manufactures brake discs, axles and gearboxes. There is also a partnership with Spain-based Talleres Alegra, a 108-year-old maker of railway track material and equipment to manufacture weldable cast manganese steel crossings for broad gauge and metro projects.

“We have seen the company grow from strength to strength,” a spokesperson for Tatravagonka tells Forbes India. “The leadership at Jupiter has perfectly executed its business strategy, as can be witnessed from its great financial performance over the past few years.”

By 2019, four years after Tatravagonka’s stake purchase, Lohia was ready for another game changer of sorts. This time, the company acquired Madhya Pradesh-based CEBBCO (Commercial Engineers & Body Builders Co) through a resolution process for Rs100 crore. CEBBCO, a listed entity, manufactures bodies for transport vehicles and railway coaches, and was a supplier to OEMs like Volvo Eicher, Tata Motors, Ashok Leyland and Mahindra. By then, Jupiter was selling some 3,000 wagons annually to the Indian Railways.Also read: AI to disrupt manufacturing sector the most: ServiceNow’s Kamolika Peres

“The previous owners had defaulted on their loans, so we acquired it from the banks,” Lohia says. “We were looking to expand our wagon business and CEBBCO had entered the wagon business at that time. They had set up wagon manufacturing infrastructure, but somehow could not get that started. By 2021, we started production there. Till that time, we were just a one-location company based out of eastern India.”

CEBBCO boasted five facilities in Madhya Pradesh and one in Jharkhand. “The acquisition gave us access to a lot of land bank, and they were also in the auto commercial vehicle business,” adds Lohia.

In 2022, through a reverse merger, Jupiter went public since CEBBCO was a listed entity. Since then, the company’s stock has soared, growing 10-fold in two years. From a market capitalisation of Rs2,360 crore in June 2022, it now stands at Rs24,000 crore, with its share price having grown from Rs55 on the day of listing on June 30 to Rs563 as of August 27.

“The wagons business has become a steady state revenue and one can expect 40 to 45 percent growth in that in FY25,” brokerage firm Dalal and Broacha said in a report in May. “However, as JWL now also looks to enter new business verticals like brake discs, wheel sets & braking systems, a lot will depend on how execution and demand unfolds in these segments, which currently have a sizeable addressable market.”

Newer Pastures

Since its listing, Jupiter Wagons has also been on a rapid expansion spree, including into newer frontiers. The company has announced plans to launch its electric commercial vehicles and has tied up with North America-based GreenPower Motor Company which specialises in commercial EVs.

“Over the next three to four years, this business has an opportunity to grow into a Rs500 crore business for us,” Lohia says. “Through some technocrats who joined hands with us and some global tie-ups, we were able to design our one-tonne commercial vehicle, which has recently been certified by ARAI and we are going to launch that vehicle by October.”

The company will follow that launch with a 1.5-tonne and 2-tonne payload variant. “The last mile is where the real conversion is going to happen into electric mobility,” Lohia adds. “The Indian market is about 600,000 vehicles per annum and over the next two or three years, even if there’s a 25 percent conversion, that’s a market of close to about 100,000 vehicles.” A wagon manufacturing bay. Image: Courtesy Jupiter Wagons LtdAs part of its backward integration process, the company acquired Stone India, once part of the erstwhile Duncans Goenka group company, for Rs25 crore through a corporate insolvency resolution process. Stone India has licences for freight brakes and, by the end of the year, the company intends to have all the certifications in place.

A wagon manufacturing bay. Image: Courtesy Jupiter Wagons LtdAs part of its backward integration process, the company acquired Stone India, once part of the erstwhile Duncans Goenka group company, for Rs25 crore through a corporate insolvency resolution process. Stone India has licences for freight brakes and, by the end of the year, the company intends to have all the certifications in place.

“Braking, globally, is governed mainly by European technologies,” Lohia says. “Through this entry, we are establishing ourselves in that segment where there is a lot of value addition. Braking is a technology-driven product, and the competition is limited.” The segment, Jupiter Wagons reckons, will drive significant replacement demand, and will help the company broadbase its portfolio, helping de-risk from the cyclical nature of its core wagon business.

Then there is the growing opportunity around wheel sets, a pair of railroad wheels that are mounted on an axle, especially in the export market. Tatravagonka, Jupiter’s minority investor, also requires wheel sets, which have been hit hard after the war between Russia and Ukraine.  Traditionally, Ukraine has been a hub for manufacturing wheel sets.That’s why in May, the company went on to acquire Bonatrans India, the Indian arm of GHH-Bonatrans, a Czech Republic-based maker of wheel sets for Rs271 crore.

Traditionally, Ukraine has been a hub for manufacturing wheel sets.That’s why in May, the company went on to acquire Bonatrans India, the Indian arm of GHH-Bonatrans, a Czech Republic-based maker of wheel sets for Rs271 crore.

Bonatrans India has a production capacity of 20,000 wheels and 10,000 axles annually, with clients including BEML, Alstom Rail Transportation India and Plasser India, among others. “India is a net importer of wheels,” Lohia says. “India does not produce forge wheels and only produces cast wheels. There’s only one plant which is the railway wheel factory, and they produce close to about 100,000 wheel sets. The demand in India is close to 400,000 wheel sets.”

Tatravagonka, too, has a demand for some 50,000 wheel sets annually, while Jupiter’s demand was about 40,000. “That’s why we acquired Bonatrans and we are now integrating,” Lohia adds. Jupiter Wagons will spend another Rs2,000 crore into that business and reckons that the capacity will grow to about 120,000 wheel sets from about 14,000 currently by 2027.

Currently, the wheel set business generates some Rs500 crore in revenue, a number that Lohia reckons will grow eight-fold to Rs4,000 crore in three years, with customers ranging from Indian Railways to Tatravagonka and metro players as India’s cities look to ramp up metro rail operations to decongest vehicular traffic.

“As of March 31, the order book totals Rs7,101 crore,” brokerage firm ULJK group said in a report on Jupiter Wagons in July. “Approximately 75 percent of this consists of freight wagon cars, scheduled for completion by the first half of FY26, with the remaining orders dedicated to the commercial vehicle business set to be fulfilled by FY25. Additionally, Indian Railways has announced plans to tender for the manufacturing of 90,000 wagons in FY25, with Jupiter aiming to maintain a market share of approximately 25 to 30 percent.”

In 2022, the Indian government had ordered 79,800 wagons from seven suppliers to supplement the already-existing 300,000 wagons, then described as the largest order of its kind. The company says that between itself, Titagarh Rail and Texmaco, they control 70 percent of the market for wagon manufacturing. Among others, the company has built wagons that cater specifically to the demands of the private sector, including a wagon that can carry SUVs on both its deck and counts the likes of Maruti Suzuki as its customers. For others such as Ambuja Cements, the company has built wagons to carry fly ash and loose cement.

Today, much of the company’s revenues come from its wagon business, followed by commercial vehicle and braking. “If you look at three years down the line, I will say wagon would be about 50 percent of the business. The wheel set business, which we are entering into, would be about 20 percent of our business,” Lohia says. “Braking would constitute about 10 percent of the business and then there’s the commercial vehicles business.”

What Next?

Today, apart from all its focus on railways and commercial vehicles, the company is also focusing on containers to house data centres. Already, it had been making shipping containers for the likes of DP World and Adani, and over the last year, it forayed into data centres. “Until now, it was mainly manufactured in China,” Lohia says. “We started with GE Renewables, and it took us a year to develop the designs. This year, that business has become Rs100 crore.”

So, will Jupiter now foray into building full-fledged bogies for the Vande Bharat trains? “Maybe down the road,” Lohia says. “But we feel that, on the private side, the opportunity is going to be much bigger on the component level rather than the fully-built trains. Vande Bharat is a high-speed train, so the components are specialised. There are very few companies who are certified to supply those.”

“Jupiter Wagon is positioned for substantial growth between FY25E and FY28E, driven by increased wagon production and a strategic diversification plan implemented by the management into segments like wheel manufacturing, brake systems and discs, E-LCV,” brokerage firm ULJK Group says. “At a macro level, the capital expenditures by Indian Railways on the Dedicated Freight Corridor are expected to introduce approximately 600,000 new wagons by 2030.”

All that means is that the rail track is set, and Jupiter Wagons is slowly chugging forward. “This is just the beginning of the journey,” Lohia says. “It’s the next four to five years when the real journey will play out. I think size matters, and as you become bigger and create good partnerships, they bring new opportunities and help you grow bigger.”

(This story appears in the 20 September, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)