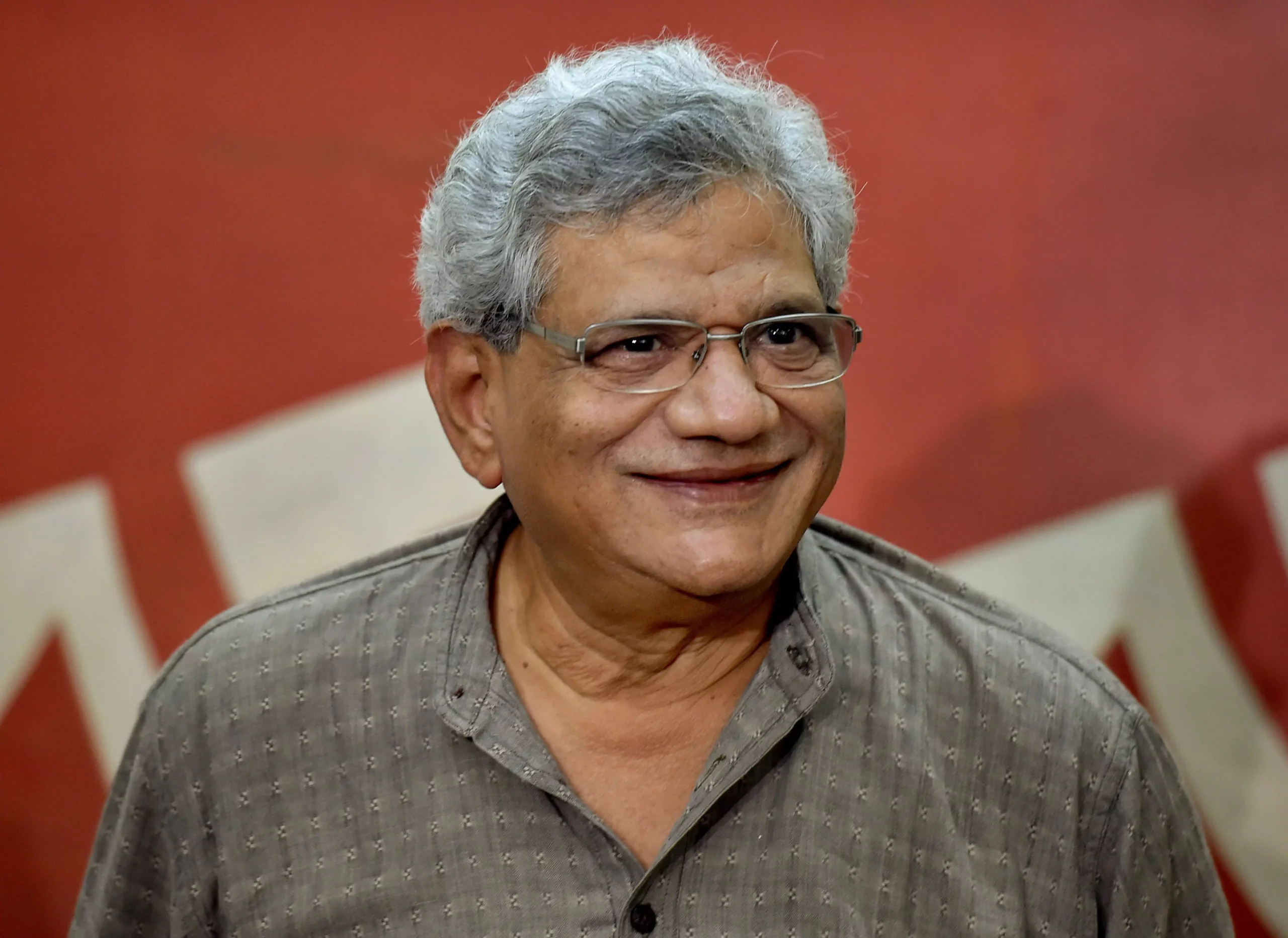

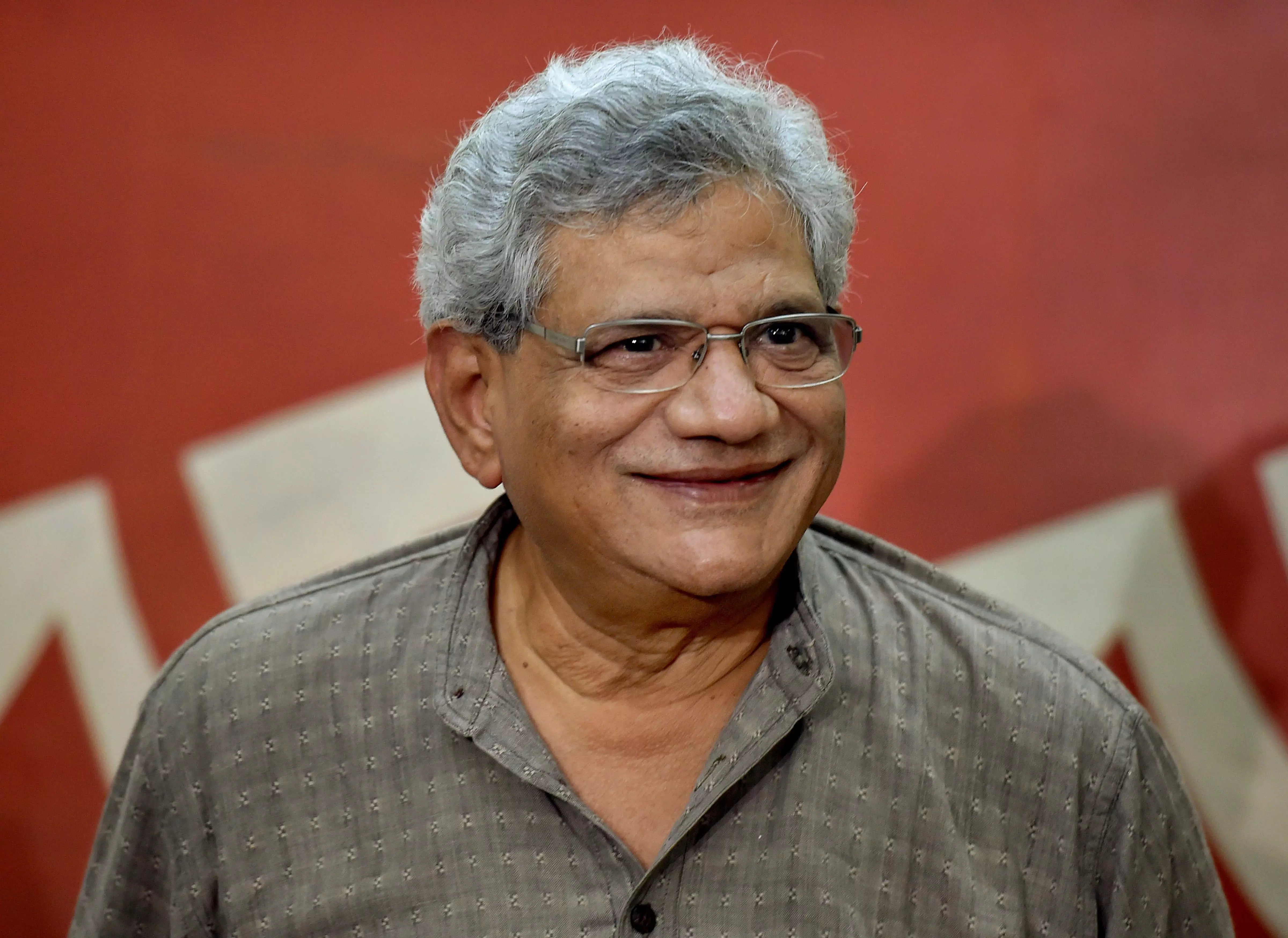

When he left Hyderabad for New Delhi in 1969, to complete his schooling that was disrupted by the separate Telangana agitation, he was still Y. Sitaram. Just “Sita” for those of us who knew him. He was at All Saints High School and I was at Hyderabad Public School but our friendship was forged at a student debating club that met at Hyderabad YMCA. A Model Lok Sabha brought together students from several schools and we formed a gang of debaters. Sita was always the star — bright, smart, witty and good-looking. He remained that till the very end. In 1966 he won a United Schools Organisation prize that took him to the United States and a breakfast with the President at the White House. The Junior Statesman, JS magazine, popular in our youth, declared him as a “Future Prime Minister of India”.

Sitaram Yechury was the first Hyderabad boy who enrolled at the then newly opened Jawaharlal Nehru University. Many of us had heard of JNU from him and followed in his footsteps. It was on that campus that he emerged as a student leader.

But he was more than that. He was the class topper in the very first batch of M.A. Economics students. Before that he had topped the high school examination and his batch at Delhi’s St. Stephen’s College. At JNU, one of his teachers found his term paper so good that he wished to award more than an “A”, and so gave him an “A alpha” grade.

Two things have been said about Sita in all the obituaries of the past few days. That he was a political pragmatist and that he was a jolly fellow, always smiling and friendly. Both attributes of a true Hyderabadi. Boss, dil pey mat lo! Chalney do, balkishen. When he was with friends from Hyderabad, like K.S. Gopal, the “water man” who was his classmate and a close buddy from All Saints, the conversation was always in what we would call “Irani cafe lingo”.

If his endearing persona was one reason for the warmth of the eulogies of the past few days, his contribution to contemporary national politics is another. Sitaram represented the true spirit of the “Left and democratic” politics of E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Jyoti Basu and Harkishan Singh Surjeet. This pragmatism was in sharp contrast to the more ideologically and organisationally rigid stance of P. Sundarayya and B.T. Ranadive that Prakash Karat came to represent. The two lines clashed on the issue of the CPI(M)’s support to the Manmohan Singh government in 2008.

As I have recorded in my book on those years, Sitaram devoted considerable energy to protect that alliance between the Left Front and the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). It was he who articulated in Parliament the 12 points that became the bottom line for Indian diplomats negotiating the India-United States civil nuclear energy agreement during the tenure of UPA-1. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh instructed his negotiators that whatever the final deal with the United States, it would have to meet all the 12 points raised by Sitaram. Even though the final deal satisfied Sitaram, ideological rigidity within the politburo resulted in the CPI(M)’s withdrawal of support to the alliance.

It was Sitaram who made me a member of the Students Federation of India and subsequently of the CPI(M). My first visit to Moscow, in 1987, was thanks to him. I was taken aback by the extent of anti-communism I encountered in Moscow. The Russian party functionary who was my escort and interpreter was himself critical of the party and repeatedly expressed a desire to visit the United States. On my return, I reported all this to Sitaram. We had many conversations in the late 1980s and early 1990s on the events in Russia and China. On the policy direction the world Communist movement was taking, especially Deng Xiaoping’s new line, and the lessons and implications for India. India too was taking a new turn at the time under P.V. Narasimha Rao’s leadership.

Sitaram was always an interested interlocutor. He heard me patiently even as we drifted apart ideologically. He remained a believer. I had ceased to be. But, we remained friends. That is what made him a truly great political leader. His ability to make and retain friendships across ideological divides. It would not have been easy, especially given the ideologically hidebound and partisan character of most intellectuals and leaders of the CPI(M). It was the Hyderabadi in him, the feeling that friendship is what counts in life, that endeared Sita to so many.

When P. Chidambaram was to present the first Budget of the UPA government in July 2004, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh asked me to check with both Prakash Karat and Sitaram Yechury whether the CPI(M) would vote against the Budget. That, under Indian legislative rules, would have led to the collapse of the Manmohan Singh government. I tried to get an assurance on this count from Prakash Karat and Sitaram. Prakash refused to meet me and I was asked to meet Sitaram. Taking his cue from Prakash’s refusal, Sitaram was not willing to give me any firm assurance. But he walked me all the way from his room in the CPI(M) office at A.K. Gopalan Bhavan in New Delhi to my vehicle downstairs, with his arm around me. We stood on the roadside in full view of several people gathered there and he bid me farewell, saying: “Give my regards to Dr Singh”.

That was the endorsement needed. Sita was like that.

It is this personal disposition and his political conviction and belief that enabled him to become a key architect of the many non-BJP coalitions governments of the 1990s and 2000s. He was the true embodiment of the spirit of “Left and Democratic Unity” that EMS and Basu espoused.

Tailpiece: Sometime in the early 1980s Sitaram, Saifuddin Chaudhury (then with the CPI-M) and I were in Khammam to address a student conference. At the end of a long day as we retired to our hotel, Sita suggested we go watch a late night showing of an NTR movie, playing at a nearby cinema. We had to catch an early morning train back to Hyderabad, why go and try to sleep now? Sita loved living life to the full.

What a shame it was cut short so soon.