What is today India’s dominant political force, the Bharatiya Janata Party, has had a history of putting a pause on its ideology for political benefit. It also discarded positions that became outdated in time. This aspect has become important today as we will look at towards the end of this column.

For instance, in the 1950s as the Jan Sangh, the party opposed Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s Hindu Code Bills because it did not accept the idea of divorce, since Hindu marriages were seen as eternal, or the ending of joint families (at root it did not want women to participate in inheritance). This position vanished with time as divorce was normalised in Hindu society and nuclear families because common in cities.

More interesting is its formal relationship with Hindutva itself. In its 1996 manifesto, for the first time, the party used the word Hindutva. This was likely because a few months earlier, on December 11, 1995, the Supreme Court had declared that Hindutva as practised by the Shiv Sena was a way of life and using it in politics did not amount to an appeal to religion. That validated the use of the word which, till that point in time, was mostly referred to negatively in the national media.

There are eight references to “Hindutva” in its 1998 manifesto, along with those to Article 370, a total ban on cow slaughter and a Uniform Civil Code. But the very next year, all of these were dropped. No Hindutva or 370 or cow slaughter or Uniform Civil Code. That 1999 manifesto has, on the other hand, five references to the minorities, assuring them of full protection and the party’s commitment to secularism. So, what changed in that one year?

It was, of course, that now the BJP was now in office. Atal Behari Vajpayee had partners in Mamata Banerjee, J. Jayalalithaa and George Fernandes, among others. He sacrificed ideology for governance. The BJP won another term that year.

In the 2004 manifesto, this time issued as an NDA document, there is again no reference to Hindutva. There is no reference to the Uniform Civil Code or to Article 370. The alliance called for an “amicable resolution” to the Ayodhya dispute.

Such shifts had been practised earlier also. In 1957, the party announced it would introduce “revolutionary changes” to the economic order, which “will be in keeping with Bharatiya values of life”. However, these were not elaborated on nor was this theme of “revolutionary change” picked up again in any future manifesto.

In 1954, and again in 1971, the Jan Sangh resolved to limit the maximum income of all Indian citizens to Rs 2,000 per month and the minimum to Rs 100, maintaining a 20:1 ratio. It would continue working on reducing this gap till it reached 10:1, which was the ideal gap and all Indians could only have incomes inside this range based on their position. Additional income earned by individuals over this limit would be procured by the State for development needs “through contribution, taxation, compulsory loans and investment”. The party would also limit the size of residential houses in cities and not allow plots of more than 1,000 square yards.

This continued under Atal Behari Vajpayee but then was dropped without explanation.

Most interestingly, the Jan Sangh said it would also repeal administrative detention laws which it said were absolutely in contradiction to individual liberty. This promise was made repeatedly in the 1950s. However, by 1967 it began to qualify the demand and said that “care will be taken to ensure that fifth columnists and disruptionist elements are not allowed to exploit fundamental rights”. In time, the Sangh and the BJP became the most enthusiastic champions of preventive detention and laws like UAPA.

In 1954 the party declared it would legislate that “tractors will be used only to break virgin soil. Their use for normal ploughing purposes will be discouraged”. This was of course because it was trying to protect the bull and ox from slaughter. Later this was dropped without explaining why. In 1951, prohibition of cow slaughter was explained as something needed “to make the cow an economic unit of agricultural life”. In 1954, the text was more religious and called cow protection a “pious duty”.

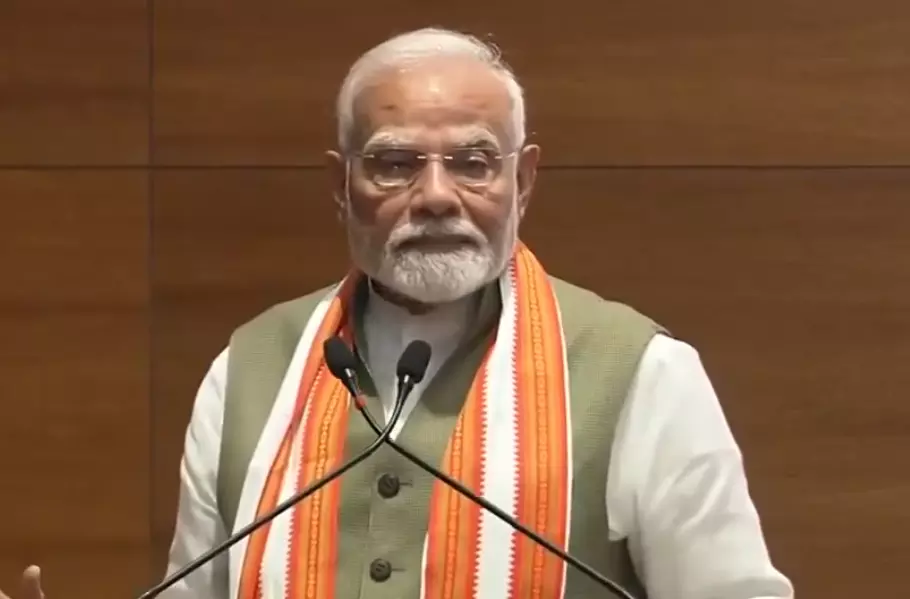

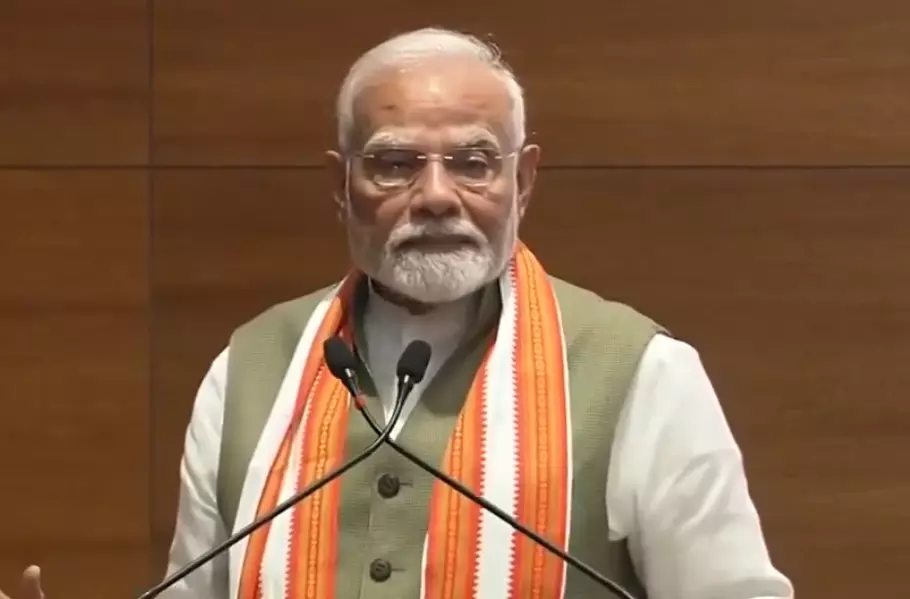

Now, what does any of this have to do with the present? It is of course that at 240 Lok Sabha seats, Prime Minister Narendra Modi does not have the power he needs to continue doing what he had since 2014. Writer Pratap Bhanu Mehta has elaborated on this: “The Prime Minister is giving a sense of being in a total funk — unable to diagnose the reasons for his defeat, and unable to chart a new course. He is on the backfoot in Parliament, not just because the Opposition is stronger and Parliament is more representative. The ability to control has gone. By all accounts, for the first time in his political career, the ability to intuit popular sentiment has disappeared and he seems like a broken record, living on the power of his past slogans that have outlived their freshness and usefulness. The imprimatur of conviction has gone.”

So what should Narendra Modi now do? The BJP itself provides the answer. Atal Behari Vajpayee wasted no time in shifting from ideology to governance. In emulating his predecessor, Mr Modi will give the secularists relief, which he is loath to do, but he will also open up more space for his party to govern. This is surely his more important concern, or isn’t it?