Amith Agarwal, Co-founder, Whole Time Director and Chief Executive Officer at StarAgri

Amith Agarwal, Co-founder, Whole Time Director and Chief Executive Officer at StarAgri

Image: Amit Verma

Amith Agarwal was instinctively trained to crack complex train equations.

Sample this: A jogger is running at 9 km/hr along a railway track, is 240 meters ahead of a train’s engine that is 120 meters long and is running at 45 km/hr in the same direction. What time would the train take to glide past the jogger? Or take this question: Two trains running in opposite directions cross a man on the platform in 27 seconds and 17 seconds, respectively. The trains, meanwhile, cross each other in 23 seconds. What would be the ratio of their speed? The young man from Alwar takes seconds to solve such questions. “All it takes is data interpretation, analysis, and mental math,” he says.

But when confronted with an equally complex life problem, Agarwal’s train of thought remained stuck for seconds, hours, and months. The mental math failed to comprehend the nature of the question. “Alwar se baahar kaisey jaana hai (how to step out of Alwar?) was the big question for the commerce graduate from the small town. Joining the family business of grain trading was an easy option.

But ‘easy’ never captivated Agarwal’s restless soul. Spending formative years in a placid Hindi-medium school gave him an easy option of either behaving like the ‘most of the class’ that didn’t question the status quo—missing teachers, poor infrastructure, and completing syllabus at the speed of a bullet train–or slog to figure out the missing questions. Agarwal embraced the second option. “Alwar was a comfort zone. I wanted to step out of it,” he says.

He finally did. After completing college, a handful of friends decided to pursue an MBA, hopped on a Delhi-bound train to join a coaching institute, and like a piercing train whistle, the five comrades marched towards a promising future. On Day One, three of the recruits booked a return ticket to Alwar. Reason? Cultural shock maimed their senses. “They gave up on the first day,” recalls Agarwal. After two weeks, two more quit. Agarwal was stranded. “

A year later, Agarwal’s train halted at a management college in Mumbai. The fast-paced journey turned rewarding in the third semester when the he landed his first internship, and then a job, with Reliance in 2004. A handsome monthly salary of Rs10,000 and a slew of attractive corporate perks made life easy. Over a year into the job, Agarwal shunned the ‘easy’ option. “I realised that I didn’t work hard to grab a job. I wanted to become an entrepreneur,” he recalls. A piece of career advice from a commodity analyst and columnist in a financial newspaper came in handy: “If you want to do something in agriculture, join a place that will equip you as an agri entrepreneur.”

But, there was a small problem. Agarwal was drawing a salary of Rs30,000, and a top agri-broking company was not willing to pay more than Rs7,000 to the fresh recruit. The bare minimum that Agarwal could settle for was Rs10,000—the amount he paid at his PG. “We can give you priceless experience but not a fat salary to train you,” was the one-liner from the top dog of the company, who sweetened the deal. “Perform for a year and then we will take a call,” was the bait.

Agarwal did a quick mental math. He had savings to foot his expenses for a year. “I just needed a year to learn and I was confident of cracking something big,” he recalls. Months lapsed, the newcomer mastered the dynamics of the agri-oil trading broking business and was ready for a bigger role. ICICI Bank was exploring new models in rural financing, and Agarwal’s boss wanted his promising gun to take a shot. Within a month, he disbursed Rs350 crore.

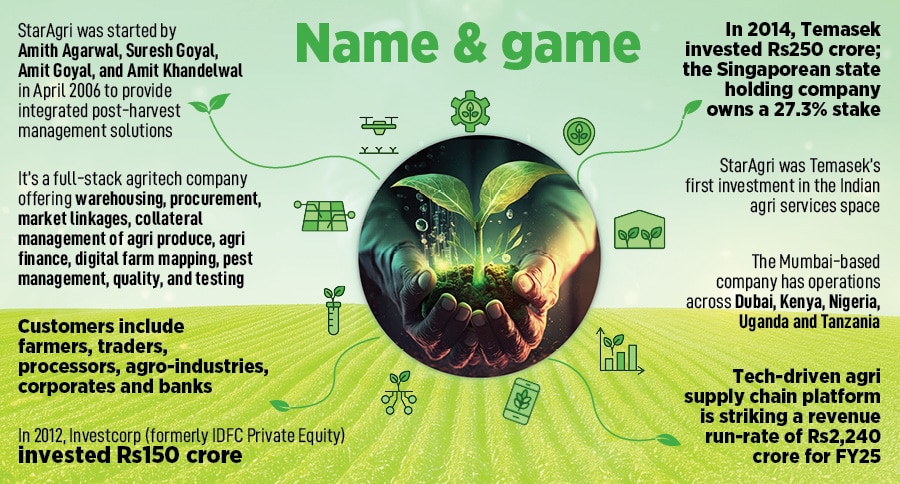

Also read: Eeki Foods: Growing more food using less

After six months, the entrepreneurial itch returned. Agarwal joined hands with three enterprising folks from Rajasthan—Suresh Goyal, Amit Goyal, and Amit Khandelwal—who were working on the same model with ICICI Bank, the stars aligned, and the friends started Star Agriwarehousing and Collateral Management in April 2006. For the first six years, the entrepreneurial journey profitably chugged along on a bootstrapped track. Even though there were irritants on the way, like operational teething problems, rejections by VCs, some investors demanding a pound of flesh such as a 40 percent stake for $2 million or a 50 percent for $3 million, StarAgri kept clocking a sedate and profitable growth.

The first turning point came in 2012. Investcorp (formerly IDFC Private Equity) invested Rs150 crore.

Over two years later, came another watershed moment: Temasek invested Rs250 crore and made StarAgri its first investment in the Indian agri-services space. StarAgri was now cruising at a breakneck pace, the ‘slow and steady’ model made way for hyper-aggressive growth, and the train from Alwar was crisscrossing the country to expand its footprint.

The dream run, though, hit a rough patch over the next three years starting 2016. The reasons were galore. StarAgri faced a series of defaults in the collateral management services business. The same year, in November 2016, India announced demonetisation, which took a massive toll on the business. To make matters worse, the period of turbulence coincided with a muted growth in agri sector. “It didn’t rain. It was pouring,” rues the first-generation entrepreneur who was grappling with trouble on all fronts. “For the first time, we slipped into a loss in 2016,” he recounts.

The forecast was gloomy. By 2019, the agri-tech funding run was losing its steam, a bunch of well-funded startups were unfolding, and the segment suddenly became unsexy. “There was a big question mark on agritech,” recalls Agarwal, underlining that days of easy funding and easy growth on the back of surplus capital were becoming a thing of the past. “We had a couple of close calls and a few near-death experiences,” he confesses.

Apart from external factors, the co-founders perpetuated something else. Agarwal tells us what went wrong. First, the rookies over-promised but under-delivered. “Forget investors, nobody would appreciate such a scenario,” he reckons. Second, the co-founders pressed the hyper-aggressive button. The temptation, he underlines, was easy money. The funding dope received in 2012 and 2014 egged them to hire at a furious pace. The result was disastrous. Expenses bloated, especially the employee salary bucket started overflowing. “From Rs1.5 crore a month, it skyrocketed to Rs8-9 crore a month,” he says.

The third mistake was something that most first-time founders are guilty of: Falling for the ‘tag.’ The friends hired CXOs and CEOs from big, legacy and marquee companies. The idea was to hire big guns, and give them ammunition to deliver. The problem with the plan was that the entire blueprint was erroneous. “We took a back seat, and the ones who were driving were not passionate enough,” he says. “Dhandha passion se chalta hai, paisey se nahin (Business runs on passion, not on money),” reckons Agarwal, adding that in 2018, the company did not have money to pay salaries.

The train from Alwar had lost its way. There was only one way out: Shun the easy way. The co-founders took control, cut excessive fat and cost, focused on sales, and streamlined operations. Slowly and steadily, the company cleared its debt and again started clocking sustainable growth. “We are now a debt-free company,” claims Agarwal.

The train from Alwar had lost its way. There was only one way out: Shun the easy way. The co-founders took control, cut excessive fat and cost, focused on sales, and streamlined operations. Slowly and steadily, the company cleared its debt and again started clocking sustainable growth. “We are now a debt-free company,” claims Agarwal.

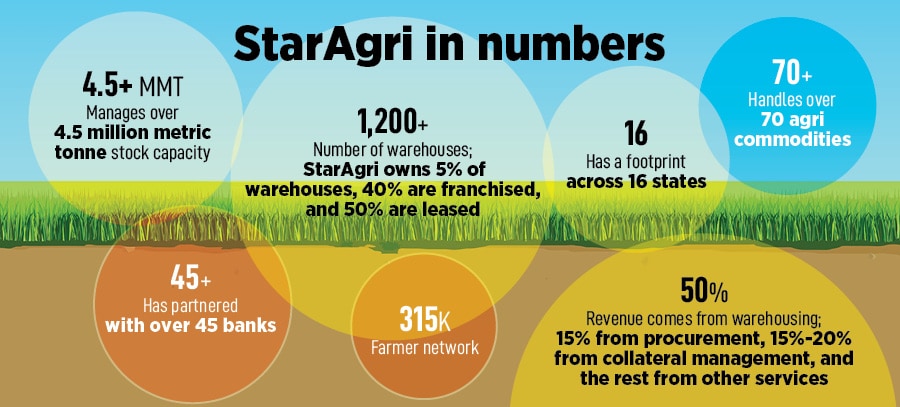

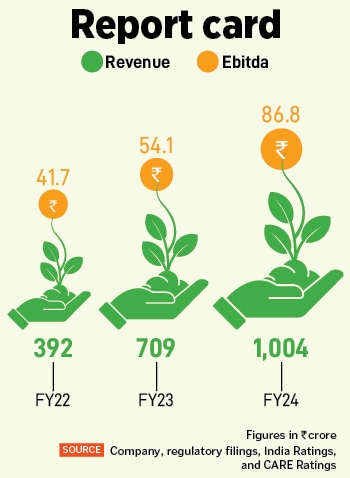

The report card looks impressive. From Rs392 crore in FY22, the revenue leapfrogged to Rs1,004 crore in FY24. “We had a PAT (profit after tax) of Rs54 crore in FY24,” Agarwal claims. StarAgri, he underlines, now manages over 4.5 million metric tonne (MMT) stock, has 1,200+ warehouses, and a footprint across 16 states. While 50 percent of revenue comes from warehousing, 15 percent is from procurement, another 15-20 percent comes from collateral management, and the rest from allied services. The Mumbai-based company has expanded operations across Dubai, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, and Tanzania. “We are now striking a revenue run-rate of Rs2,240 crore,” claims Agarwal.

A recent brokerage report decodes what has worked for the company. StarAgri, points out Care Ratings in its brokerage report released in July 2024, has been de-risking operations to improve efficiency. The company has taken steps such as moving towards an asset-light model and implementing stringent risk control in collateral management and other business segments. “The aim is to minimise future credit and liquidity risks,” the report says, highlighting that the company has inbuilt clauses in its contracts to cover the risk. “If they do not receive timely rentals and other allied service charges, they have an option of selling off the stocked goods and adjust the liability,” it adds.

Despite a steady growth, challenges remain. One of them is intense competition in the warehousing business. StarAgri, Care points out, faces competition, which leads to an increase in warehouse lease charges borne by it at strategic locations. “Warehouse owners at prime locations will offer their premises to companies offering higher rents,” the report underlines, adding that the industry has a bunch of established players, and it is not always possible to pass on the rise in warehouse rentals completely. “The company is also exposed to the risk of crop failure in a particular location which may lead to sub-optimal utilisation of the warehousing space,” it warns. There are other red flags in a high working capital nature of operations and ever-challenging agri-business.

Agarwal, for his part, points out a different kind of challenge. “We need to get farmers on the app,” he says, adding that the farmer is still not the end user of technology. “The biggest challenge is to make farmers embrace technology and use it extensively,” he says. The tough task, though, is something that only the co-founders will have to execute: Under-promise, over-deliver, and shun hyper-aggression.