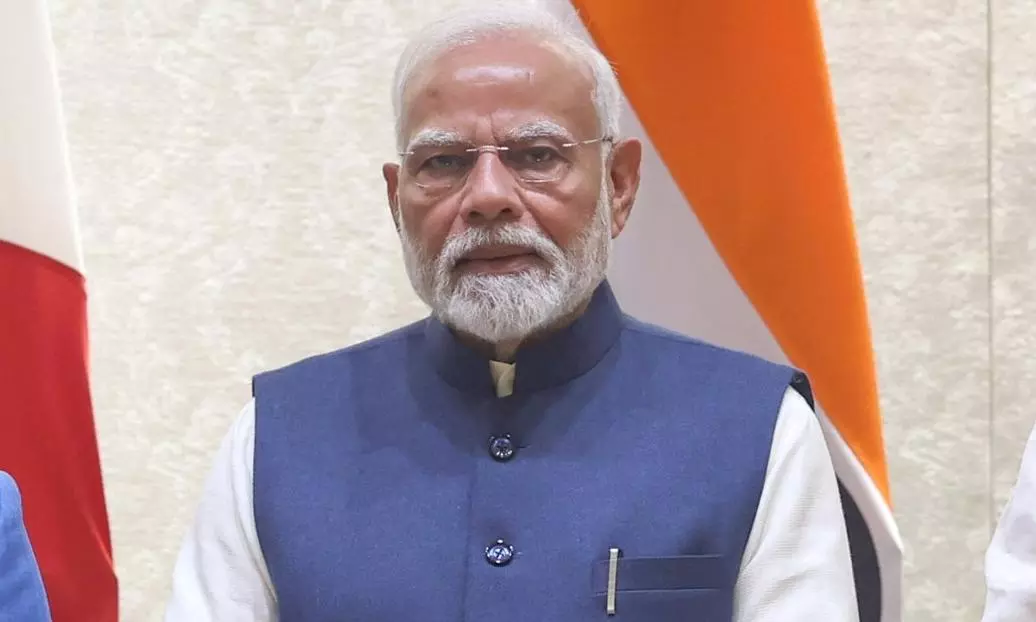

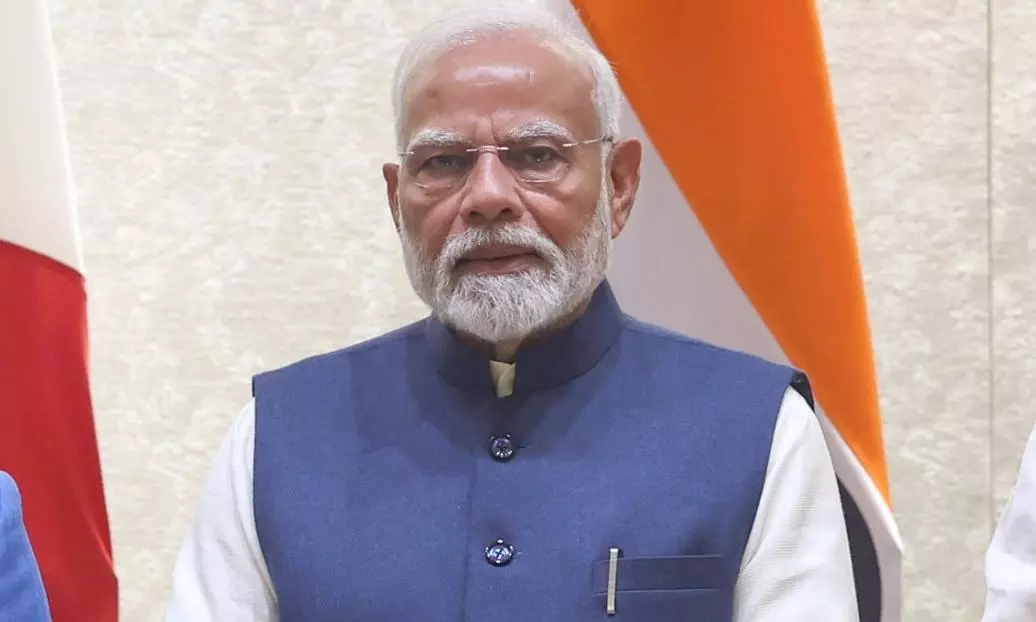

While campaigning for the Lok Sabha polls, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had promised to roll out within 100 days of being re-elected an action plan that would transform India. His grand design, that is unlikely to succeed, is the “One Nation-One Election” decision by the Cabinet, specifically the minority BJP-led coalition government that can’t work without a complicated constitutional amendment.

The bottom-line is that the Modi government doesn’t have a mandate from the voter to get the “One Nation-One Election” plan going. Mr Modi ought to know it; if he has gone ahead without the mandate, it will require political skill to cover up a basic blunder of this magnitude.

Already there is speculation that the grandiose plan, a political masterstroke to align all elections with Mr Modi or the BJP’s schedule of elections across India and in all three tiers of the democratic structure, may end up on the backburner, that is, sending it to a Joint Parliamentary Committee.

If Mr Modi’s plan to hit the ground running in his third term is to bury in a committee a major reorganisation of the political timetable and the constitutional structure required to implement “One Nation-One Election”, then it’s time to start asking if he knows what he is doing and, more important, does he know how to get things done?

It is obvious by now that the BJP and Mr Modi as its star campaigner, political mastermind and principal strategist, do know what they cannot do; they cannot risk holding elections in Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Haryana, Jharkhand, Maharashtra and Bihar all at once. If the BJP wanted and Mr Modi had the appetite for it, a common schedule for elections in these four states and two Union territories could have been worked out.

By ducking out of this, which could have aligned six more states with the schedule for the next Lok Sabha polls, Mr Modi has made it clear that he is unsure of his ability to persuade voters to choose the BJP over other parties in these states and Union territories. Putting into practice instead of preaching about the advantages of “One Nation-One Election” may have been a little more convincing than this charade that Mr Modi has chosen to perform.

Elections are not merely technicalities, nor are they just the means of winning a majority for the winner to quickly form a government and get on with the business of wielding power. Elections do enable a leader become the cock of the heap — Prime Minister, chief minister and even panchayat sabhadhipati — but that is not their sole purpose.

Elections require the hoity-toity “netas” to canvass for votes; it teaches the high and mighty, every so often, that all the paraphernalia of being the cock of the heap depends on the approval of the ultimate sovereign, that is, voters. Throwing the weight of the elected majority around is not the aim of elections. Elections deliver a mandate, a verdict giving the leader of the majority a lease to run the government for a period of time that could be five years or less.

Holding office at the pleasure of the people comes with its own discomforts; displeasing the people has consequences. There are states in India where voters choose different parties in Lok Sabha and state Assembly elections, like Rajasthan and Karnataka; there are states that have more often than not changed the ruling party every five years, like Kerala and Rajasthan; there are states that seem fascinated by the ruling party and keep voting them back to power, like West Bengal or Gujarat.

Voters make their choices in different elections for different reasons. A “One Nation-One Election” plan has failed to factor in that voters may not appreciate the clubbing of parliamentary and Assembly elections, where different issues and different priorities are in play. It may suit Mr Modi and the BJP to fit a few select specifics of local concern into their larger narrative of protecting the purity of the nation through a process of homogenisation by talking about Rohingyas, Bangladeshis and infiltration by antagonistic illegal Muslims in Jharkhand to scare tribal voters that they will be marginalised, swamped by outsiders. It may suit them to defend Hindutva hegemony by talking about opening up opportunities in Jammu and Kashmir by abrogating Article 370 and ending the special privileges that it guaranteed to local communities. But these may not be the priorities of voters in these states.

A political party and its leadership that disregards the diversity of India’s people and their priorities is a danger to itself and the idea of unity despite the multiplicities in a democracy. The immediate local concerns of people must be foregrounded in Assembly elections and at a more granular level in civic and panchayat elections. The three tiers of elected bodies were designed to reflect the differences between national, state and local concerns.

In the last many Assembly polls, Mr Modi has been relentlessly pitching himself as the face of the BJP, as the icon voters must remember when casting their vote. Bundling every issue and concern into one package may serve the BJP’s purpose, making it easier for Mr Modi to campaign. But that is not how others campaign. Demonising Rahul Gandhi as “terrorist number one” may work for voters in J&K and Haryana, by polarising votes, but that’s not what will work in Jharkhand or in Maharashtra.

One size does not fit all. To compel voters and states to fit the BJP’s schedule of “One Nation-One Election” in the expectation that it will increase its political strength with more seats in Parliament and in the states cannot be India’s goal, as a State or even as a nation. It is not enough for the Congress and the parties of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance to talk about defending the Constitution on behalf of the people; these parties need to raise public consciousness on how the Constitution and democracy could be endangered through the idea of “One Nation-One Election” and by extension, “One Party-One Leader” politics.

Regardless of the number of votes and other technicalities of pushing through a constitutional amendment, there are critical political and ideological issues that the rest of India’s political class must raise in order to defend democracy in practice and stop authoritarianism in its tracks. The “One Nation-One Election” overturns the fundamentals of democracy, about peoples’ power and their right to decide. It takes away the basics of initiating change by stripping people of the power to make decisions and periodically revise their decisions, through different schedules for different elections.