(From left): Tanuj Bhojwani, head, People+ai; Tanvi Lall, director of strategy, People+ai; Vishnu Subramanian, founder, Jarvis Labs

(From left): Tanuj Bhojwani, head, People+ai; Tanvi Lall, director of strategy, People+ai; Vishnu Subramanian, founder, Jarvis Labs

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

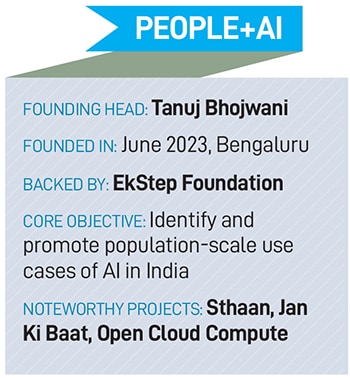

About 10 years ago, Tanuj Bhojwani was a tad ahead of his times in trying to build a drone-based services startup. Back then, instead of the regulatory support that’s coming together now, there was scepticism and even suspicion, and therefore the startup folded eventually.

The experience got Bhojwani thinking about “who’s had more success with the government,” and people in his professional networks pointed him to an ecosystem of public-private tech solutions that Nandan Nilekani was evangelising, which today we know as India’s digital public infrastructure (DPI).

Bhojwani, also an alumnus of IIT Bombay like Nilekani, got involved, starting around 2016, and got an insider’s view of what population-scale tech platforms and solutions could look like—and built differently from the VC-funded startup model. (Through Covid, he and Nilekani even teamed up on a book, titled The Art of Bitfulness, about how not to get overwhelmed by our digital gadgets—nothing to do with DPI.)

And then ChatGPT happened. Bhojwani got it to write an essay on India Stack (Aadhaar, UPI, e-KYC, Digilocker, direct benefit transfer and so on), and shared it with Nilekani and a few others he’d come to know through the DPI work. “Hire this bot,” replied Nilekani, tongue-in-cheek.

In April 2023, many of those involved in DPI met for a powwow in Bengaluru, where ideas, solutions, PoCs etc were showcased on what generative AI could mean. The realisation was sinking in these circles that those invested in the success of DPI needed to answer the question: “What is the UPI of AI?” Meaning what would a DPI for artificial intelligence look like that would bring the benefits of AI to India’s masses.

In April 2023, many of those involved in DPI met for a powwow in Bengaluru, where ideas, solutions, PoCs etc were showcased on what generative AI could mean. The realisation was sinking in these circles that those invested in the success of DPI needed to answer the question: “What is the UPI of AI?” Meaning what would a DPI for artificial intelligence look like that would bring the benefits of AI to India’s masses.

And it also became clear that an organisation should exist to find and champion that answer, and foster the partnerships it would entail. Thus was born People+ai, in June 2023, and Bhojwani started as its founding head.

Because of Nilekani’s backing, People+ai was started under the auspices of EkStep Foundation, the tech-for-education non-profit that he and his wife, philanthropist Rohini Nilekani, founded in 2015.

“We are like an incubator of population scale (AI) ideas, but we’re not giving money and taking equity,” Bhojwani says. “What we are giving is the support network that we can to help these people (startups) grow. And in return what we are asking for is, hey, please remember this and pay it forward.”

People+ai, wherever it can, will also support the creations of protocols or standards, tools and data sets, all of which can be maintained by open source contributors. These can help anyone developing an AI technology with India in mind.

Work at People+ai has four objectives: Finding population scale use cases for AI in India, building the infrastructure required to take these use cases to the population at scale, creating communities and spaces where people from different backgrounds can collaborate and build AI tech and solutions, and cheerleading and storytelling, to get the word out about people building these solutions.

Work happens via both the organisation’s own staff, and through a growing network of volunteers from the industry, who are, typically, highly qualified in their own fields. Someone could be a machine learning engineer, or an AWS (Amazon Web Services) solutions architect or an outreach manager.

Over the last year or so, projects that have started at People+ai include Jan Ki Baat (people’s voice), Sthaan (place) and Open Cloud Compute.

Unlike in the rich countries, and with big-tech solutions that tout RAG-enhanced bots (retrieval augmented generation), what if the bot itself were to initiate the conversation, and in a user’s native tongue? That’s the idea behind Jan Ki Baat.

Imagine an AI bot asking a person who’s eligible for a government scheme, “Hey you just got this scheme from the government. Did you understand the benefits? Did somebody ask you for money? Did you have to pay a bribe?”

Bhojwani says: “Based on the feedback on what they’re saying, that data is recorded, captured, stored, and then you can use AI to analyse it and act on that feedback.”

In the case of Sthaan, it’s an attempt to build a protocol for AI-based (including voice to voice) solution to help locate people easily. In India, many people don’t have addresses, or have addresses that don’t convey ‘Where they are?’ and ‘How to reach them?’, according to the opening lines of the charter document of this project. Sthaan as a protocol gives them a way to answer these questions easily by assigning user-friendly identifiers, according to the document.

Open Cloud Compute, as you’ll read ahead, is an attempt to build a network of micro data centres and make it available to anyone looking for such compute resources, including for developing AI solutions.

Other examples of population-scale projects at People+ai include an effort to fast-track green building certifications, another to help some 63 million hearing impaired people access AI and communicate better, and a project that’s working on how AI might be applied to provide mental health support.

Also read: ‘AI will provide an upside to enterprise software adoption’

The case for micro data centres

If People+ai’s overarching aim is to support population-scale AI solutions for India, Open Cloud Compute is an example of how that aim translates to a specific project.

Open Cloud Compute is, obviously, younger than People+ai, but it addresses an important question: “Let’s say there are many use cases and applications developed to cater to our pan-India population,” Tanvi Lall, director of strategy at People+ai, who heads this effort, says. “How then would these use cases practically be executed in the field?”

Open Cloud Compute is, obviously, younger than People+ai, but it addresses an important question: “Let’s say there are many use cases and applications developed to cater to our pan-India population,” Tanvi Lall, director of strategy at People+ai, who heads this effort, says. “How then would these use cases practically be executed in the field?”

In other words, where would we find the computer and network infrastructure on which these applications would reside and run. “So, compute infrastructure naturally emerged as a place where focus needed to be put as one of three pillars,” Lall says, “when you think about compute, data and models.”

Given that they all belong to the DPI community, the common ask was—just as UPI—a standardisation protocol, enabled private fintech players, or more recently, something on the lines of the ONDC (open network for digital commerce), for compute.

If you look at this as a two-sided network, on one side are the providers of compute and data centre services in India. And there can be many of them so that there is a level playing field for smaller and newer players to provide their products and services in this market.

On the other side, from the demand perspective, are users, consumers, various other entities, large enterprises who look for compute, network, storage products and services, AI services and so on. They should be able to find this compute infrastructure on demand and shouldn’t be just reliant on a few global providers. They should be able to easily discover domestic providers as well the ones that are emerging today in India.

It’s widely accepted in the industry and among investors that the demand for cloud infrastructure and services is projected to strongly increase over the next five years. In the context of AI, there’s also a shift from the older CPU-based compute to the newer GPU-based (graphics processing unit) methods, and further, even more specialised techniques such as accelerated compute.

In this backdrop, OCC is attempting to do the following: Make this market more competitive in India by offering more choice for the customer, and second, if there is choice, ensure that there is also interoperability. OCC is working on the standards that can make that happen, if the providers embrace them.

Keep in mind that as of now it’s a project that’s less than a year old. They kicked it off in December 2023, and made their first presentation at the Global Tech Summit that month in Delhi.

Since then, they’ve been working to identify the smaller and newer players of AI services, AI compute, and even CPU compute that are emerging in India, and are trying to package and sell this in innovative manners. And then, Lall says, “can we bring them on to a discoverability interface, which is powered by standardisation?”

An important aspect of OCC is that it will rely on a “disaggregated, decentralised approach,” Lall says.

This leads to one of the most interesting parts of OCC—micro data centres that can be placed close to users… even in small towns and villages, eventually as the use cases scale up. Experts will tell you that when it comes to data centre needs for generative AI, there’s the training part and then there’s the “inferencing” part, which is where we actually use a trained model—giving it inputs and seeking results.

The heavy-duty needs are for training, and a lot of the inferencing can be done on less powerful processors. Today, compute services providers are coming up with innovative ways of offering it in India, Lall says, although this is a nascent development. And the economics of micro data centres are increasingly becoming favourable, she adds.

For example, it’s possible to set up a solar panel that can provide enough power to run, say, a 3,000 square feet data centre that can be set up close to the customers.

Today, there isn’t even a widely accepted definition of micro data centres. In a public consultation paper that OCC released, they’ve provided certain recommendations based on power consumption, the space needed, and so on.

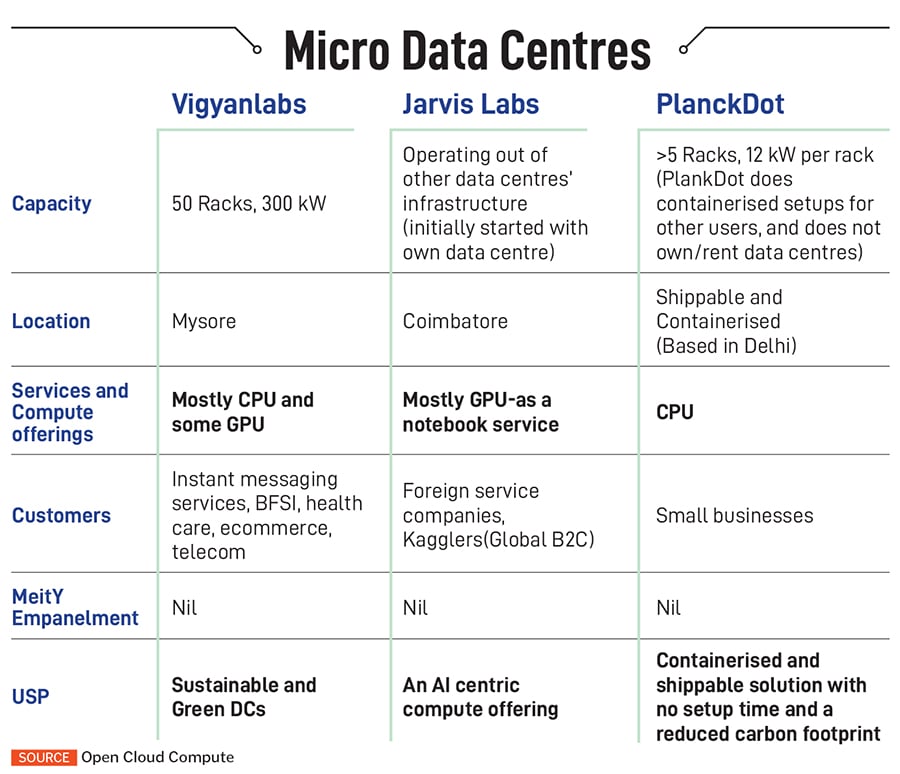

There are only about 10 micro data centre providers in India, OCC estimates. Among them are Jarvis Labs—you’ll read more on them later—PlanckDot, Vigyanlabs, AssistanZ Networks and NetForChoice Solutions. Each of them is tackling a different aspect of the overall cloud infrastructure ecosystem that can also be harnessed for the development of AI.

In the coming months, we’ll hear more about OCC’s partnerships with some of these companies and the first real-world use case pilot deployments. In the years to come, OCC hopes to catalyse the establishment of a large grid of micro data centres across the country.

AI infrastructure on tap

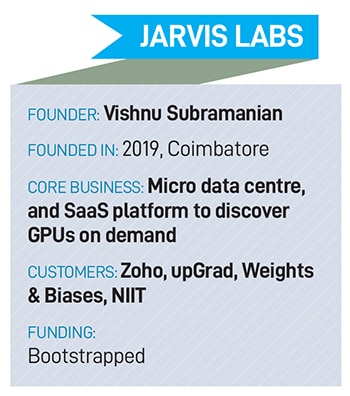

Jarvis Labs was born out of founder Vishnu Subramanian’s fascination with open-source software, which started more than 10 years ago when he was at Wipro, and his exposure to Kaggle. “Think of Kaggle like an Olympics for data scientists,” he says.

He then decided to build his own GPU computer, but discovered that a single GPU wasn’t enough for him to work on problems in Kaggle. More recently, about a year before the Covid-19 pandemic, he decided to upgrade to a 4-GPU machine, using Nvidia’s GeForce RTX 2080ti graphics cards, which had to be imported.

He then decided to build his own GPU computer, but discovered that a single GPU wasn’t enough for him to work on problems in Kaggle. More recently, about a year before the Covid-19 pandemic, he decided to upgrade to a 4-GPU machine, using Nvidia’s GeForce RTX 2080ti graphics cards, which had to be imported.

These were part of Nvidia’s RTX 20 series, which introduced real-time ray tracing capabilities and Tensor cores for AI-driven features. Ray tracing refers to a rendering technique, where rendering is the process of generating a final image or animation. Tensor cores are specialised cores designed to accelerate deep-learning computations.

Thus was born the initial version of Jarvis Labs, to build these desktops—upgrading to A6000 chips—along with the software and sell it to customers. Supply chain disruptions from Covid-19 meant shipments were indefinitely delayed for the chips Subramanian wanted, but that turned out to be a blessing in disguise. He shifted his attention to a cloud offering, which opened up Jarvis to customers anywhere.

Subramanian and his small team of engineers worked to bring down the time it took to spin up one instance of a GPU from about five-seven minutes for an expert to about 15 seconds. This was in 2021, and at the time “it was the fastest in the world, probably,” he says.

On the outskirts of Coimbatore, Jarvis started as a cloud offering with four servers with eight RTX 5000 GPUs each. Today, “we have scaled up our infrastructure. We moved from our server room to a proper tier 3.5 data centre,” he says. And in a second pivot—the first being switching to the cloud offering—instead of buying servers, Jarvis is partnering with other companies that are investing heavily in hardware and data centres, including in overseas markets.

Subramanian and his colleagues have also built an “orchestration layer”, which allows customers to tap the GPUs and run their software applications, and they’ve brought down time to get a GPU going from 15 seconds to four seconds now. This is where they were also ready to become part of the Open Cloud Compute (OCC) story—they had become a platform where customers can find GPUs offered by various third parties, which they could access via Jarvis.

“When we started out, AI was at an exploration phase,” Subramanian says. One had to run various software, experiments and so on. “Now we are talking about, how can I deploy an AI model in a particular region and cater to that particular audience… we are partnering with some of the big companies, which allow us to launch these instances across the globe, 20-plus different locations in the coming months.” And going serverless allows Jarvis to offer customers a way to use the GPUs in a matter of seconds. Users don’t have to worry about complex software or processes.

They only need to run a few basic functions and Jarvis will convert the functions into production-ready (ready to use) end points (computer jargon for a point of communication in a network or software platform etc). These can also be increased or decreased in capacity as needed.

Next, with an API-as-a-service approach (API is application programming interface), Jarvis is opening up from the first techie users to a more general audience such as business professionals, doctors, artists, journalists, and so on. The APIs allow users to not worry about what’s happening under the hood and instead benefit from the power of GPUs and AI applications.

Among individual users of Jarvis are researchers from companies like Tesla, Meta and some US universities. On the enterprise side, customers include upGrad, Zoho and NIIT in India, Weights & Biases, an AI developer platform provider, University of California, and so on. Today, Jarvis has close to 40 customers, Subramanian says. The collaboration with OCC is with respect to access to GPUs for schools and colleges and hospitals.

A common problem that people often ignore is that “it’s not just the GPU that matters, it’s also the software stack that you put on top of that,” Subramanian says. “We have been working on the software stack and we have been talking to students, doctors across the world. We know the kind of complexities these guys face. So, we fall into this particular space where we actually help them access the most affordable GPUs.”

As the micro data centre grid starts taking shape, if OCC succeeds, say there are 100 of those in India, as the critical mass gets built up, a company like Jarvis can also “push them to the global audience, give them an international market along with Indian market,” Subramanian says.

(This story appears in the 04 October, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)