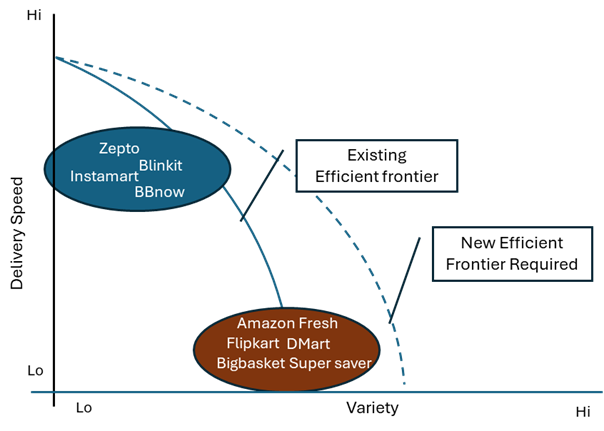

How do QC firms shift the delivery speed vs. variety trade-off frontier (See Figure 1) without a significant increase in cost and decrease in customer expectations?

How do QC firms shift the delivery speed vs. variety trade-off frontier (See Figure 1) without a significant increase in cost and decrease in customer expectations?

Image: Shutterstock

You are startled by your alarm at 7 am for an important meeting only to find an empty shower gel bottle with absolutely zero squeezes left. What do you do? Just open your phone, make a few clicks, and within minutes, you will have the shower gel delivered to your doorstep. That’s Quick Commerce (QC), the newest consumer addiction on the block.

Launched to serve the needs of a time-starved, urban consumer seeking Uber convenience, the promise of a short, exact delivery time is a significant value addition in consumers’ lives that QC firms Blinkit, Instamart and Zepto deliver. The business model’s success has inspired Amazon, Flipkart and BigBasket to roll out their versions of 10 min convenience. QC platforms need to store goods close to customers in warehouses (known as dark warehouses) that cost much more (on a per square feet basis) than warehouses located in places farther than consumers. And punctuality requires a higher number of delivery executives to meet erratic demand.

The twin value propositions of speed and punctuality are spurring repeat purchases and higher average order value. However, repeat purchase also depends on the selection and availability offered by QC platforms. Consumers prefer a high ‘Basket completion rate’, i.e., a percentage of the products a customer needs are available while placing the order. Moreover, the minimum order value for free delivery forces customers to order a minimum basket size and the platform needs to offer customers a larger selection to meet it.

“Give an inch, and they will take a mile” is the pithy insight that all firms playing in the QC arena are discovering about their consumers. Apart from daily essentials, QC platforms now sell stationery, towels, ceiling fans, mixer grinders, and T-shirts. All of this adds to the second layer of costs—the inventory costs—the cost of the product (inventory) in the warehouse.

A typical QC warehouse that housed around 2,500 distinct products (Stock keeping units – SKUs) two years ago now stores about 6,000 SKUs. The inventory cost in the ‘essentials’ category sits on the QC platforms’ seller’s book, e.g., Moonstone Ventures LLP (for Blinkit). However, much of the ‘non-essentials’ or ‘non-urgent’ inventory cost is on either the books of the brands selling it or their distributors—this model is popularly called the marketplace model.

Imagine a seller’s or brand’s plight. In the (almost) erstwhile same-day/next-day delivery by Amazon and Flipkart, sellers kept their inventory in 30 odd fulfilment centres. Now, they need to decide which of the 250 QC replenishment centres that service 1,500+ dark warehouses the seller needs to keep the inventory in. They will incur massive costs of fragmentation of the inventory across multiple locations and multiple QC firms. The problem is quite daunting and will keep growing.

Over the years, supply chain management wisdom has recommended that firms choose between high delivery speed and high variety to offer an appropriate cost to serve that the consumer is willing to pay. The trade-off is known as the efficient frontier (Figure 1). For example, supermarkets such as DMart keep 25,000+ SKUs near customer locations and promise a delivery time of 2-6 hours.

The critical question, therefore, is: How do QC firms shift the delivery speed vs. variety trade-off frontier (See Figure 1) without a significant increase in cost and decrease in customer expectations? The efficient frontier in the diagram represents a combination of delivery speed and a variety of performances that will yield a profitable cost to serve and enhance customers’ experiences.

Figure 1: QC shifting the efficient frontier

Figure 1: QC shifting the efficient frontier

Shifting the efficient frontier

QC firms seem to leverage Assortment Science with hyperlocal experimentation to push the frontier. Their tech armour makes them data-rich. Within three to four months of launching a dark warehouse, consumer search and purchase behaviour insights drive their inventory policies and help them craft just-in-time replenishment processes with precision for locally preferred products. This information helps reduce inventory costs and is invaluable to sellers who are increasingly at the mercy of the QC platforms.

Also read: Zomato’s Blinkit has a great durable competitive advantage over Flipkart: Sanjeev Bikhchandani and Deepinder Goyal

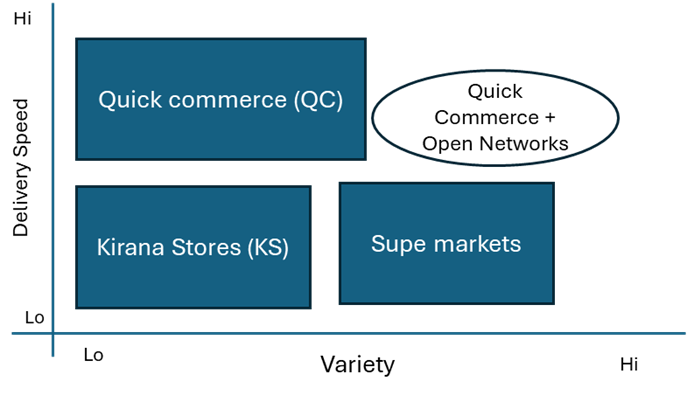

A possible win-win solution for QC platform and sellers: Adoption of Open Networks for a tiered inventory policy

The answer may also lie in a clever adaptation of the QC platform to Open Networks such as Beckn-operated ONDC. Open Networks allow sellers (brands or their distributors) and buyer apps such as QC platforms (who aggregate demand/consumers) to exist as independent entities on the network, i.e. sellers need not necessarily be on the QC platform. This allows any customer on a buyer app (e.g. QC platform) to have access to products from all sellers on the network. Open Networks thus enable the discoverability of a large variety of items.

QC thrives in bustling cities (85 percent of demand is from 10 top cities). These places also tend to have a very large diversity of local traders and retailers that cumulatively (yet independently) invest in placing inventory of a large selection of goods and cater to local customer demand. These shops have accumulated local customer knowledge over the years. Because of their small size, they can quickly sense changes in customer profiles and adapt their selection.

The QC platforms can offer their selection to consumers via a tiered inventory policy. For most frequent items with stable demand, they will control the inventory to enable adherence to less than 15-minute service levels. When a customer lands on a QC platform, the QC platform’s own inventory is made available first. If the brand or SKU is not offered or is out of stock, the customer is exposed to inventory available at the partner seller’s location. The customer can add the product to the QC platform cart and execute one transaction in one go. Delivery timelines, of course, would be broken into two and products delivered at different times.

Such a configuration allows customers to offer a large variety without compromising on delivery time for critical items and offering an acceptable delivery time for non-critical items. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Quick Commerce + Open Networks

Figure 2: Quick Commerce + Open Networks

QC platforms may be deterred from this approach due to the risk of a negative consumer experience or loss of loyalty to the platform. However, they are best poised to engineer supply chain collaboration technology for consumer experience. Channelling consumer search across multiple inventory groups necessitates seamless transactions with multiple parties—a promise that Open Networks, which is operating on the Beckn protocol (ONDC), aims to deliver to all entities on the network.

ONDC is exploring novel e-commerce use cases. QC+, a hybrid approach (platform + network), would be an interesting use case to test. As for the risk to customer loyalty to the platform, the perception of low availability (or out-of-stock) might have a larger impact on loyalty or repeat purchases. Of course, the product margin share between the QC firms and sellers needs to be worked out, and it is possible that this approach might work for a few categories.

QC+ approach allows QC platforms to grow without disrupting existing markets (kirana stores and supermarkets) and provides platforms to work towards SDG 17, i.e. encouraging effective partnerships between the various stakeholders in the community for the overall good.

About the authors: Prof. Sheila Roy, Associate Professor, Operations & Supply Chain and Quantitative Methods, SPJIMR and Aditi Shah, PGDM student, SPJIMR.

Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan’s S.P. Jain Institute of Management and Research (SPJIMR), is a leading postgraduate management institute, recognised by the Financial Times MiM Global Rankings as India’s #1 business school, by Business Today as one of the country’s top five business schools, and by the Positive Impact Rating, a Swiss association, as one of the top five business schools worldwide in terms of social impact. With its innovative and socially-conscious approach to management education, research, and community engagement, SPJIMR aims to influence practice and promote value-based growth of its students and alumni, organisations and its leaders, and society at large.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from SP Jain Institute of Management & Research, Mumbai. Views expressed by authors are personal.]