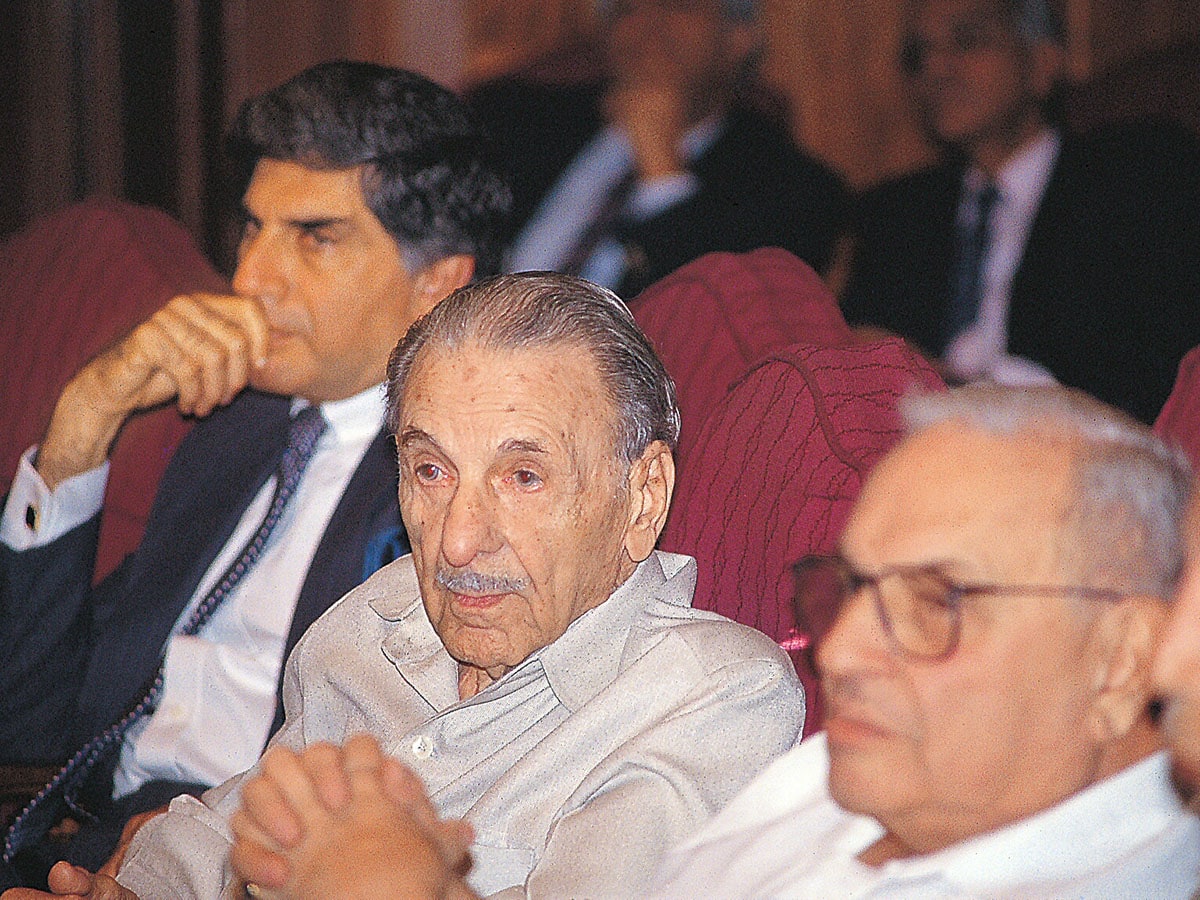

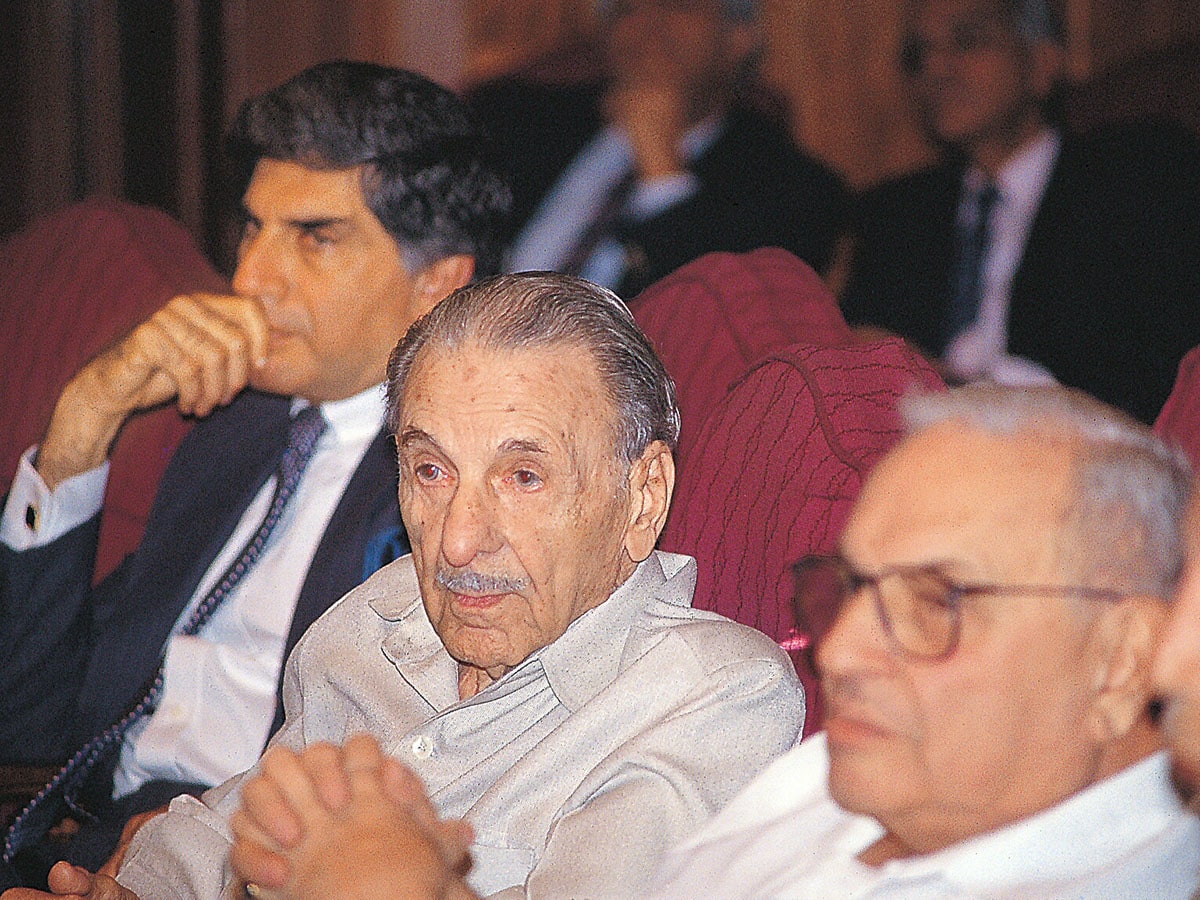

JRD Tata Along with Ratan Tata and Russi Modi at the meeting in New Delhi, India

JRD Tata Along with Ratan Tata and Russi Modi at the meeting in New Delhi, India

Image: Hemant Pithwa/The The India Today Group via Getty Images

The Indian government’s go-ahead to Tata Electronics earlier this year to build a mega semiconductor fabrication facility in Dholera in Gujarat in partnership with Taiwan’s PSMC is in many ways Ratan Naval Tata’s (RNT) crowning glory in the universe of technology and innovation. Technology today is at the forefront of the 30-company conglomerate operating in 10 verticals, with IT services bellwether TCS leading the charge.

Within the tech vertical, there’s also Tata Technologies that got listed on the Indian stock exchanges last November and is at the vanguard of engineering next generation connected and autonomous electric vehicles. And then there’s Tata Electronics, a greenfield venture founded in 2017, to manufacture precision components, which will execute the $11 billion (a little over Rs91,000 crore) semiconductor project.

RNT, who studied structural engineering and architecture at Cornell University in the United States, almost took up an offer from IBM when he returned to India in the early 60s. Tata Sons Chairman JRD Tata convinced him to join the Tata group instead. After stints with Tata Motors (then known as Telco) and Tata Steel (then Tisco), RNT did a short spell at the two-year-young TCS in 1970.

The first up-close tryst with leadership and technology came a year later when RNT was appointed director of National Radio and Electronics, or Nelco, then an ailing maker of engineering products like radios and radio components, among many others. RNT did show his turnaround skills in the four years spent there, but more important was the experience garnered at a company that today operates in the areas of VSAT connectivity, satcom projects and integrated security & surveillance systems.

Also read: Ratan Naval Tata: Legend Through The Years

The Nelco stint is significant because at that time TCS was still a fledgling company and the Tata group was known more for making locomotives and heavy vehicles. The shift towards high technology began when RNT was appointed chairman of Tata Industries, the promoter company of the group, in 1981. In 1991, the year in which the economy and businesses were unshackled, he took over from JRD as chairman of Tata Sons and of the trusts.

Over the next two decades, the transformation would call for several radical changes. Brushing off the cobwebs of the license raj and embracing free markets with pent-up abandon, RNT set about identifying the key drivers of the strategic shift.

One of them was internationalisation, a prong of which was foreign collaborations for knowhow in what would become verticals of the future—aerospace & defence, consumer & retail and automotive, to name three. That paved the way for collaborations with marquee names, from Elexi and Hitachi, to more recently Starbucks, Boeing and Analog Devices.

An international mindset would also result in a rejig of top talent, infusing fresh blood either from within or from non-Tata companies or from overseas. This also meant that empires and fiefdoms had to be dismantled. Storied names in corporate India, from Russi Mody to Darbari Seth, had to make way for younger blood. In 1997, Ajay Kerkar, referred to in the media as the ‘czar’ of the Taj group of hotels, was ousted in the boardroom, with RNT lieutenant RK Krishna Kumar swiftly appointed as chairman. A few years later, Raymond Bickson, a native of Hawaii, was appointed COO—and a year later CEO—of the Taj group of hotels, one of the first international appointees in the Tata C-suite.

Also read: Tata Technologies wants to diversify into EVs and semi-conductors. Will competition and pressure play spoilsport?

More expats would follow—Darryl Green from Vodafone Japan was brought into Tata Teleservices and Alan Rosling from the British Prime Minister’s Policy Unit became Tata Sons’ first non-Indian executive director. His mandate: Internationalisation of the Indian conglomerate.

With a fresh team in place at key companies, and non-strategic businesses like cement and soaps exited, the stage was set to buy big assets overseas. After buying UK beverage brand Tetley, the commercial vehicle business of Daewoo of South Korea and British soda ash giant Brunner Mond in the first half of the 2000s, the stage was set for the big one: The $12.1 billion buyout of the London-headquartered Corus group. Like most acquisitions, not all of Tata’s gambits played out as blueprinted, but they doubtless displayed RNT’s ambitions to make global multinationals of his flagship companies. By the time RNT retired from Tata Sons in 2012, two-thirds of the conglomerate’s revenue was coming from overseas. That momentum sustains till date, with group companies operating in over 100 countries in six continents.

RNT remained chairman of the powerful Tata philanthropic trusts, which own 66 percent of Tata Sons’ equity. That also ensured that although he had hung up his Bombay House boots, he hadn’t quite faded away. The process of choosing his successor wasn’t smooth and, a section of observers felt, lacked objectivity.

The big picture today, though, of Tata Sons is a bright one. A conglomerate with a presence in strategic areas of nation-building—just as founder Jamshedji Tata had envisioned in the 1860s. Today, vital verticals that include steel and infrastructure have that extra edge that RNT sought to inject from the 80s onwards: High technology and innovation.