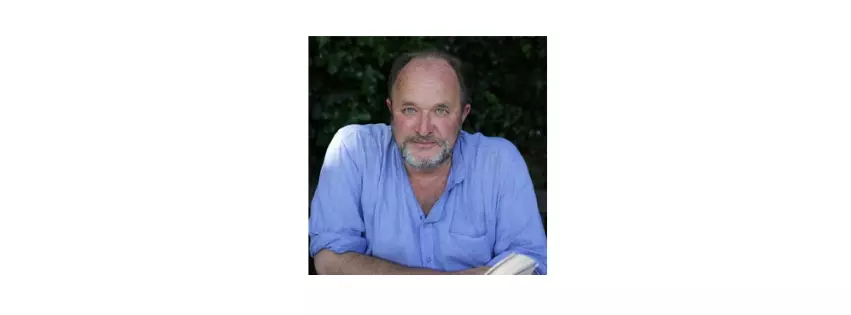

Rather than chest-thumping, Indians should invest more in the study of history. This is the advice of Scottish historian William Dalrymple whose latest book, The Golden Road, is all about the influence wielded over the world by India. In conversation with Sucheta Dasgupta, he explains how it came to do so and why it is important that we both explore and share this knowledge.

In the first century CE did India have a greater per capita income level than Rome?

Very difficult to say. There are estimates given by Angus Maddison who has analysed ancient history and come up with figures of GDP and GDP per head but honestly, I think, these figures rely on very, very slim evidence. By the 18th century, though, you get patchy figures which show India producing vastly more than Europe although Indian society has always been much more extreme in terms of differences in distribution of wealth.

What is the Golden Road and why is it called such?

The Golden Road is my own name for the maritime trade routes which supported and enriched India. It is meant to be taking on the largely mythologised story of the Silk Roads. The Silk Roads, which everyone takes as established historical fact, is a term invented only in the 1870s by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen who called it Das Seidenstraßen. Marco Polo doesn’t talk about it, no ancient Chinese source talks about the Silk Roads, no ancient Roman source talks about it and the Romans bought most of their silk from India. Not before the 13th century in the Mongolian period does it acquire some relevance. What we do know, however, is that there are some extremely busy maritime routes running on the monsoon winds between the Red Sea coast and the mouth of the Indus right down to Kerala at the time, and Strabo, the Greek geographer, says he went to the port of Hormuz and he sees 250 vessels leaving in a great fleet for India. Pliny, who is a naval commander, calls India the drain of all the precious metals from Rome, attacks what he calls degenerate Roman women for wanting silks which allows their bodies to be seen beneath the wraps, and he doesn’t like pepper, and considers these things as unnecessary luxuries, annoyed that wealth from Rome is draining out of Roman hands and pockets. We have some figures, because we have something called the Muziris papyrus which is a detailed invoice for one particular container travelling on a third century ship called the Hermapollon and what has amazed everyone is the enormous value of the Indian luxury goods in Roman money. In return, India imports Roman wine because there is a surprising taste for it in ancient India; there are many, many amphorae of wine dug up in Arikamedu in Muziris and at other Indian ports. It is entirely misleading to imagine as two current shows in London do, one in the British museum and the other in the British Library, that China was the primary destination of those trade routes, and I have written an article in the Observer about this.

What was the genesis of the book?

It was a trip to Ajanta 10 years ago seeing the newly conserved frescoes in Cave Ten that got me writing about this period again and then having visited Angkor Wat after a long time and learnt about the newly discovered Buddha heads and triad of Hindu gods on the Egyptian coast of Berenike. One could really see the extent of the diffusion of Indian ideas going up to Siberia and Mongolia, on one hand, and, on the other, to Egypt in the West.

How did you first come to know about Wu Zetian, the only female emperor of China who ruled in her own right?

I owe that to a wonderful Bengali scholar called Tansen Sen who is the leading Indian historian on China. Tansen’s parents were Marxists and he was brought up in China. He was a journalist, speaks fluent Chinese and is currently with the New York University, Shanghai campus. Wu Zetian is a very popular figure in Chinese soap operas and entertainment culture because she is a concubine and beautiful and sexy, on one hand, while, on the other, she is cruel and powerful, and leaves behind a trail of bodies. I also owe my thanks to Himanshu Prabha Ray, Roopinder Singh and Nayanjot Lahiri. What I hope I have done with this book is to bring all this together in a single volume and to break down the silos which often separate Buddhism, Hinduism, mathematics and science; try and give a full picture not of the history of India but the history of the diffusion of Indian ideas outside India which I think has not been done since A.L. Basham’s 1954 book, The Wonder that Was India.

In a time when India is a laggard not only economically but in the world of ideas, forever taking the cue from the West in technology, education and culture, don’t you think it is inappropriate to extol our past glories and call us vishwaguru?

No, I think it is very important for people to understand their history and to understand it actually. One of the problems with Indian history is that there is a general impression that anyone who is interested in the Mughals is somehow a Marxist and anyone interested in ancient India is somehow a member of the RSS. There is so much in India’s history to be proud of, to have the confidence to look at your past and say, this was such a magnificent civilisation. It passed not through the power of the sword or bayonet or through the march of jackboots but it passed through ideas. And the way it should manifest is not in the flat way where you are jingoistic or you look down on other countries but through investing in the study of it. India’s museums are shockingly underfunded. The ASI is appallingly under-resourced. Only one-tenth of Nalanda has ever been excavated. This is the greatest engine of Indian science and soft power. Huge resources should be devoted to it. I was recently in eastern Turkey and the hotels there are about thirty years behind India but their museums are magnificent. Erdogan’s government has actually invested in history. India, incidentally, gets fewer tourists than Singapore. A mile from here, for instance, even in Mehrauli, the Zafar Mahal, is disintegrating but nothing has been done to prevent this.

Brahmagupta, as we know, was the first to expostulate on the qualities of the zero. How did this knowledge to travel to the West? Who was actually the first to discover zero?

The zero, as a placeholder, is there from Babylonian times. Babylon seems to be the first to have had it as an expression of nothingness. But what Brahmagupta did was to define zero as a number with its own properties. And he came out with a number of statements, such as zero is the number you get when you subtract a number from itself. Thus he defines the rules of zero and so gives zero its power as an active number rather than a passive placeholder. And that allows for the decimal system, the binary system and a whole variety of fancy mathematical tricks. You can express any number up to infinity with just the nine digits and zero.

The travel of the zero to the West is, on the other hand, like a two-stage relay race. In 773, a delegation arrives in Baghdad from Sindh and they bring with them something which has been specifically requested by the vizier of Baghdad, a book that the Arabs called The Great Sindhind, which seems to be a compilation of two works of Brahmagupta plus Aryabhatta. The vizier himself was no stranger to Indian learning; he was a man called Khalid ibn Barmak, Barmak being an arabicisation of the Sanskrit word, pramukh, or boss, and the Barmakids, as his family was known, were hereditary abbots of a Buddhist monastery in Afghanistan. They convert to Islam and they bring with them the knowledge of Indian mathematics to the Arab world and the first thing they do to when they are made viziers of Baghdad is to get the actual texts. They also in time import Indian works on ayurvedic medicine and Charaka and so on to Baghdad. For four generations, they run the Abbasid Arab empire. And in that time, a huge range of Sanskrit books are brought in and translated into Arabic.

The second stage takes place when a young man turns up from what is now called Uzbekistan, in those times known as Khwarazm. He is known in Baghdad as Al-Khwarizmi. And Al-Khwarizmi also can read Sanskrit and he retranslates all these texts into a single, clear Arab text that he gives the snappy title of The Compendious Book of Calculating by Balancing according to Hindu Calculation. This book becomes known by a nickname, Al-Jabr, which is where we get the word, algebra. And his name, Al-Khwarizmi, is where we get our word, algorithm, from. So this guy has given these two crucial words, and they travel all the way to Spain.

But it is another 400 years before it travels properly to the West and the person who brings it is a young man who is brought up in Pisa and he is brought to Algeria’s port of Beijaya by his dad and he goes to the local school and learns Indian mathematics. He goes back to Pisa when he is 18 and discovers everyone around him is doing MCMXVI times CTMVXII, the Roman method of calculating. So he writes a book called the Liber Abaci and that young man is Fibonacci.

We would like to know what is next on your agenda.

It could be a family history or it could be the opium wars, although I am more into ancient history at the moment.