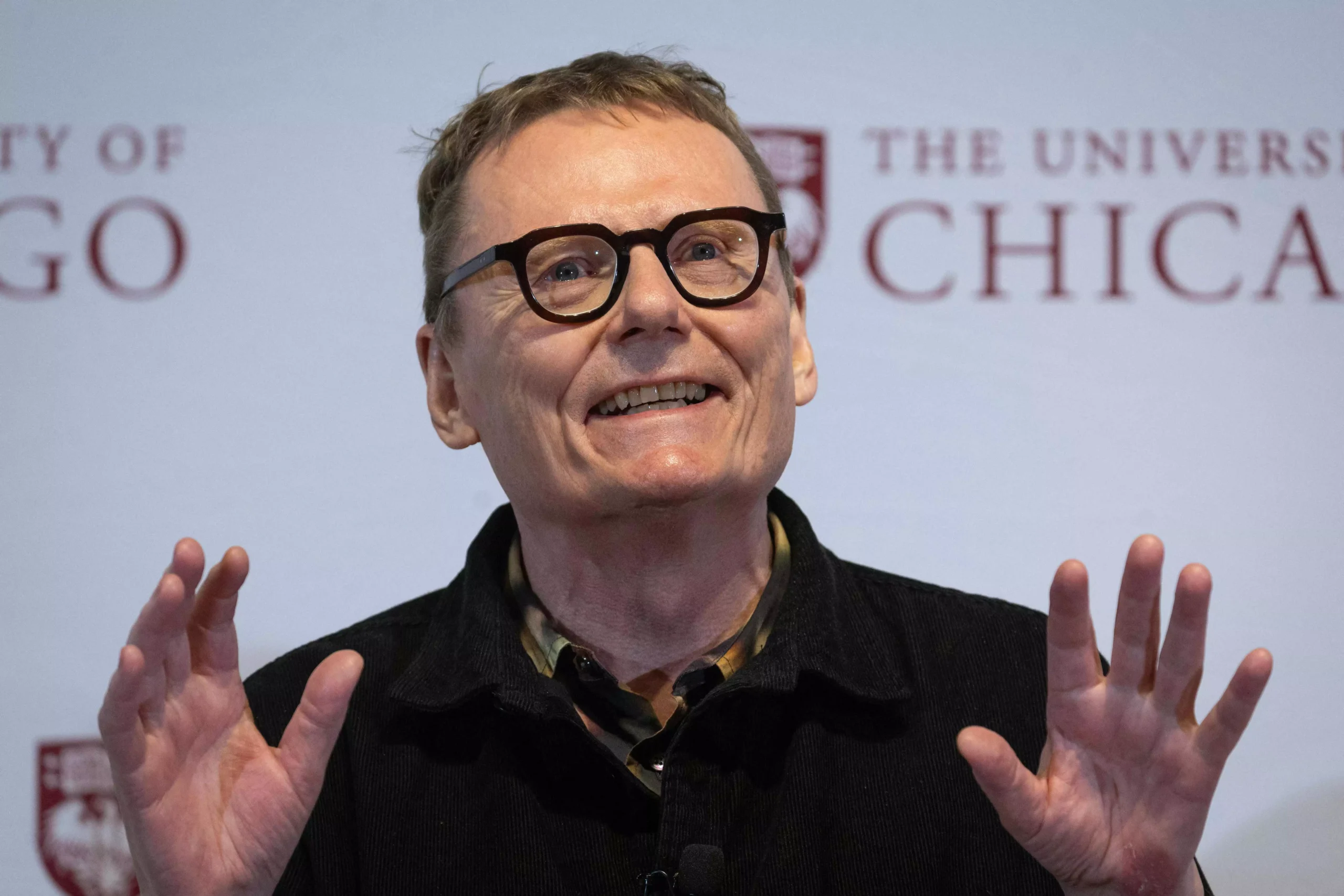

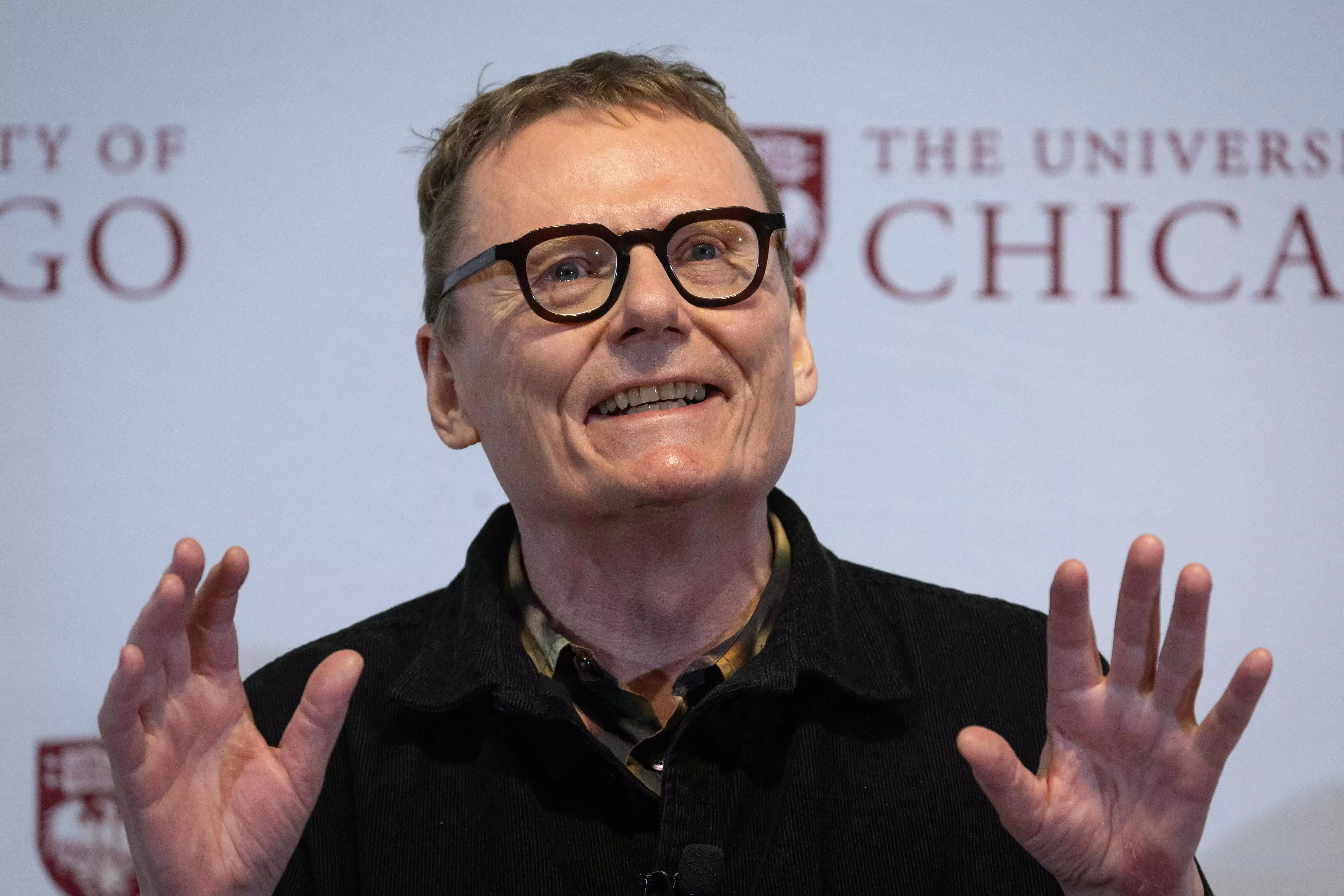

Three academics based in the United States — Daron Acemoglu from Turkey and Simon Johnson and James Robinson from Britain — won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics for research that explored the aftermath of colonisation, to understand why inequality persists even till today, especially in countries that are dogged by corruption and dictatorship.

According to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences release: “This year’s laureates in the economic sciences — Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson — have demonstrated the importance of societal institutions for a country’s prosperity. Societies with a poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better. The laureates’ research helps us to understand why.”

Prof. Acemoglu is the base of the triangular partnership linking the two Britons. He is an economics professor at MIT. He co-authored with James Robinson (then at Harvard University) Why Nations Fail and Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. In 2023, he co-authored with Simon Johnson the book Power and Progress: Our Thousand Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity.

But their foundational work together began in 2004 when in a joint paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson empirically and theoretically demonstrated that economic institutions play a fundamental role in the differences in economic development around the world. They postulated that: “Economic institutions encouraging economic growth emerge when political institutions allocate power to groups with interests in broad-based property rights enforcement, when they create effective constraints on power-holders, and when there are relatively few rents to

be captured by power-holders.”

Why Nations Fail is an eloquent, profusely researched and extremely scholarly analysis of these repeated failures. The book begins quite dramatically with the description of the entirely different situations of the two halves of the town of Nogales portioned by a fence to be parts of the United States and Mexico. The Nogales in Arizona in the US thrives, while the Nogales in Sonora in Mexico languishes. The climate is alike. The lay of the land is alike. The populations too are alike. Why? The authors tell us why: “The answer to this lies in the way the two different societies formed during the early colonial period. An institutional divergence took place then, with the implications lasting into the present day.”

In other words, the difference was because of how the United States and Mexico evolved differently with very different political and economic systems. One system evolved to milk the land for the colonial masters in Europe, while the other evolved due to the colonisation by the settlers and for their benefit.

Suggesting that if the United States did not free itself in 1776, it might have evolved differently. Like India, perhaps?

Speculation aside, the book tells us “that while economic institutions are critical for determining whether a country is poor or prosperous, it is politics and political institutions that determine what economic institutions a country has”. The authors forcefully argue that achieving prosperity depends on solving some basic political problems. It is important to grasp this and to help us do just that the authors take us through a spectrum of time and geography to illustrate how and why some nations evolved into prosperous and more equal societies, while others languished as highly unequal societies. Some states are structured around “extractive political institutions” where the institutions serve to satisfy the aspirations of a narrow elite alone.

Colonialism was clearly an extractive political system. But does India still have an extractive political system? Many an economist will argue that the data suggests just this.

When we see the evolving politics through this prism, we have an answer for the growth of family or clan dominated political parties on one side, and the notable expansion of the upper classes and the growing power of family-owned businesses.

Standing in sharp contrast to the nations dominated by extractive political institutions are the nations based on inclusive political and hence economic institutions. This is amply evidenced by why and what happened in England that made it the centre of the Industrial Revolution. The precursor to this was the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as a result of the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English parliamentarians and the Dutch stadtholder, William II of Orange. King James II’s overthrow began modern English parliamentary democracy. The Bill of Rights of 1689 became one of the most important documents in Britain’s political history and ever since then the monarchy has never held absolute political power. The consequent development of pluralistic political institutions opened new vistas of education and unleashed long dormant creative powers stifled for long by a system that conferred monopolistic extractive powers to a small class.

The overthrow of King James II precipitated a directional change in Britain and it harvested the benefits for the next 250 years or so. Historical turning points such as this led to far-reaching consequences. The death of Mao Zedong and the rebirth of Deng Xiaoping from the “living dead” who was held in Shaunggui, a unique institution in China for the detention of senior Communist Party leaders, would easily be another. One day history may become more charitable towards P.V. Narasimha Rao, who heralded the dismantling of the centrally planned state and the industrial controls central to it with just a single plainly worded administrative order.

Why Nations Fail is a hugely researched study, and a truly educative book that takes you all over the world in its examination of why some countries prospered and others didn’t. This is the sort of book that must be made required reading for anyone who aspires to shape, mould or lead this nation, or even serve it in more mundane ways.

But that might be a tall order for a political system where leadership is inherited, or dictated by a secret cabal, or where a bureaucrat’s rise to administrative leadership is not a result of merit or achievement but due to the passage of time and service time. Finally, it is a book for all those who care about their societies and dream of things that never were and wonder why not?