Rahul Bharti, executive director, corporate affairs, Maruti Suzuki India

Image: Madhu Kapparath

In September, when Ford Motor Company announced its intention to reopen its Chennai plant—it had stopped operations in 2021—primarily for exports, the development grabbed headlines. Although the American automaker has not revealed details of its plans, there have been news reports of the company exploring options in the light commercial vehicle and pick-up segments, in both internal combustion engine and electric options. There have also been news reports of potential partnerships with other automakers, with Volkswagen being named as a possible candidate. Ford declined to comment for this story.

Ford’s announcement brought into the limelight, once again, the various factors that have contributed to the uncertain performance of European and American carmakers in the highly price-sensitive and competitive Indian automobile market. However, Ford’s announcement also puts the spotlight on the emergence of India as an export hub for foreign carmakers. Whether it is Maruti Suzuki, which entered the Indian market in 1981, or Kia Motors, the youngest kid on the block that entered India in 2017, exports are becoming an increasingly significant part of their strategies, and revenues. While Indian exports have conventionally been sent to markets in Africa and Latin America, Japanese carmakers such as Honda and Maruti (58 percent of its equity is held by the Japanese Suzuki Motor Corporation) are now exporting passenger vehicles to their home country as well, marking a shift away from a general perception that Indian products were not good enough for developed markets.

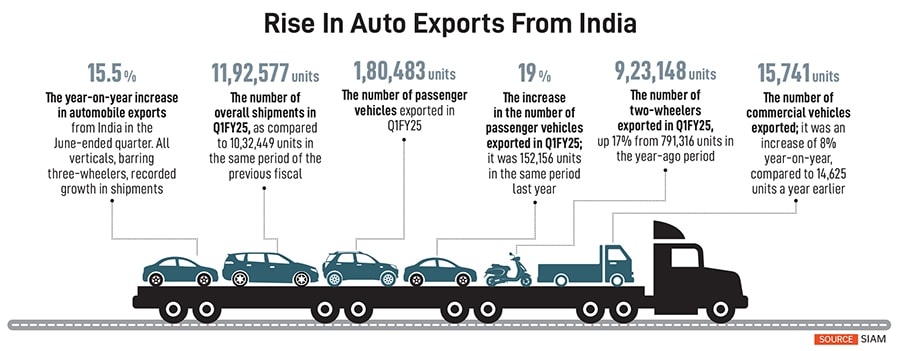

“In 2024, the number of cars exported from India was about 6.7 lakh units,” says Hemal Thakkar, senior practice leader and director, Crisil. “Exports have increased as a total percentage of sales, to 15 to 16 percent.” He adds that earlier, more than 50 to 60 percent of exports comprised hatchbacks, whereas about 20 percent was SUVs; today, SUVs comprise about 40 percent of exports.

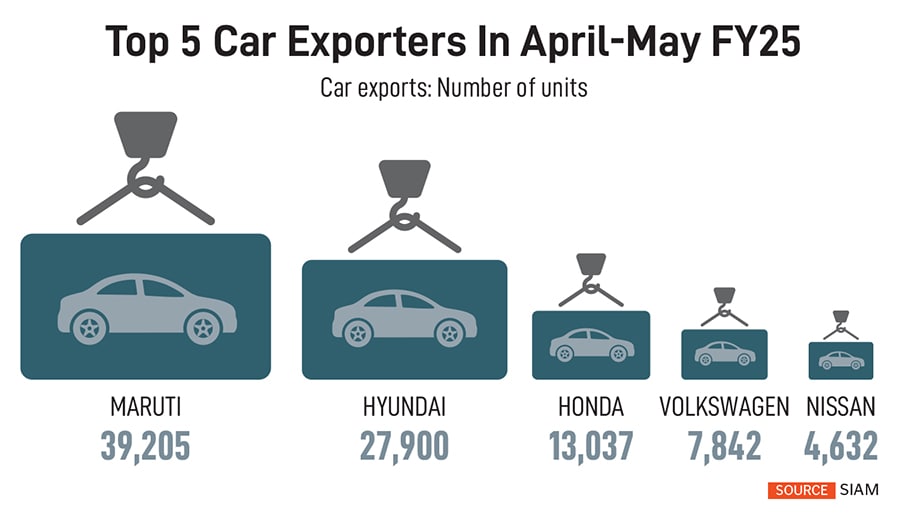

Maruti Suzuki—the largest exporter of passenger vehicles from India (see box)—had been exporting vehicles to Europe since 1987-88, but this had remained a small number of units and had never gone mainstream. “Given the vision of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Viksit Bharat programme, we realised that the ambition cannot be fulfilled by domestic demand alone. India has to take a larger share of the global market, which is by exporting more. And it became clear to us, whether it is for India or for our own business, we have to export more and we have to grow it exponentially,” says Rahul Bharti, executive director, corporate affairs, Maruti Suzuki India Limited (MSIL).

Consequently, the company’s exports have increased by three times over what they were around four years ago. “And, by the turn of the decade, we should grow by another three times from where we are currently. So, we were exporting around 96,000 units in FY21, while last year we did about 2,83,000 units. We hope to export something like 8,00,000 by 2030-31,” says Bharti. “We are not growing in percentage terms; we are growing in multiples.”

Bharti also feels that exports are the fire test of global competitiveness in technology, cost and quality. “If you are exporting, and in good numbers to a good number of countries, it’s quite clear that your product is globally well-accepted and competitive,” he explains, adding that consumers in India, too, would be delighted to get a vehicle that is at par with global standards.

MSIL is exporting 17 of its 18 models to about 100 countries. Its major markets include Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia and Middle East, and is entering Europe and Japan. As MSIL begins to launch electric vehicles (EVs) in 2025, these will also form part of its export portfolio. Exports to Japan include the Fronx, which commenced recently, and Baleno in the past.

Bharti claims that in the past four years, MSIL’s compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) for passenger vehicle exports has been more than five times (44 percent) over its competition, whose exports CAGR was 8 percent. “We aim to increase our volume by three times in the next 6 years, between 2025 and 2031,” he says.

The volume of cars being exported by MSIL has led to the company setting up a railway siding within the premises of its Gujarat plant; it was inaugurated in March. This was done with the intent to minimise damages and increase efficiency during transportation to the port. The company also plans to use the siding to increase the volume of cars it sends to other parts of India.

Nissan Motor India sells the Magnite, in its domestic and export markets. Between FY24 and FY26, the Japanese carmaker is targeting to sell 1,00,000 units in exports

Nissan Motor India sells the Magnite, in its domestic and export markets. Between FY24 and FY26, the Japanese carmaker is targeting to sell 1,00,000 units in exports

“Export is an important piece of our overall strategy,” says Saurabh Vatsa, managing director, Nissan Motor India. “Our business strategy is based on three pillars: One is a strong focus on the domestic market, second is an equally strong focus on the export business, and third is the relaunch of our CBU [completely built up] business in India.”

Currently, Nissan India sells the Magnite, in its domestic and export markets. Alongside, it has X-Trail, which is part of its CBU segment. As part of its mid-term plan, one that it calls The Arc and which stretches between FY24 and FY26, the Japanese carmaker is targeting to sell 1,00,000 units in exports. The company is going to introduce two new compact SUVs in India: One will be a five-seater and the other a seven-seater. It is also working on introducing an affordable EV. Along with increasing its export target to 1,00,000 units, Nissan India also plans to sell the same number of units in India by FY26.

The existing Magnite (available as a right-hand drive variant) was being exported to about 20 countries, while the new version that was launched in October, showcases the first left-hand drive variant, which will be exported to more than 45 countries. “So, the total number of markets that we are going to be exporting this vehicle to is going to be more than 65,” says Vatsa. “We are developing India as a massive Nissan export hub, and whatever cars that we are going to introduce in India, they are going to be exported as well.”

Vatsa says today’s consumer in India is well-versed with technologies, and is also demanding where features are concerned. “Therefore, when you cater to the Indian market, you are able to meet the requirements of customers in a large part of the world. We do not intend to differentiate between the cars we sell in India versus what we export.”

Nissan has a plant in Sunderland, UK, which is one of its biggest export hubs, with India emerging as one of the biggest export hubs in the AMIEO (Africa, Middle East, India, Europe and Oceania) region.

Also read: How safe are the cars you are driving on Indian roads?

What’s fuelling exports?

Several factors have spurred the volume of automobile exports from India. While some of these have been direct consequences of the government’s role in signing various kinds of trade agreements with the governments of other countries, others are results of improved technological and manufacturing knowhow and prowess among carmakers.

“Global original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) have realised that the cost of manufacture is lower in India, because of the lower cost of labour and other input materials, and higher productivity levels,” says Thakkar of Crisil. “Earlier, German manufacturers, for example, would make their vehicles in India, but would import their transmission parts from their home countries or other manufacturing centres. This has now changed in favour of India, as these carmakers are getting more confident about making entirely in India, and exporting as well.”

Proving Thakkar’s point is Volkswagen India, which experienced strong export demand in FY24 and shipped 44,180 units. It recorded a 63 percent year-on-year growth, from 27,137 units in FY23, thus becoming the fourth largest auto exporter from India, up from being the sixth largest in FY23.

Behind Volkswagen’s rise has been the German carmaker’s made-in-India Virtus, a global sedan, with 31,495 units exported, an increase of 74 percent from FY23, and the mid-size SUV Taigun with 12,621 units, up 59 percent from FY23.

Thakkar adds that the presence of large ports such as Mundra in Gujarat, JNPT in Navi Mumbai, and in Chennai has been an enabling factor. “Congestion levels at these ports have eased, which has a positive impact on logistic costs,” he adds.

This is evident in the fact that MSIL’s manufacturing facility in Gujarat is the one from which it exports most of its units, while Nissan exports from its Chennai plant. According to reports, the plant at Oragadam has the capacity to produce 480 cars per day; as of March, it was producing 178 cars a day, half of which were being exported.

In July, media reports said that Tata Motors is planning to set up a ₹9,000-crore Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) plant over 400 acres near Panapakkam in the Ranipet district of Tamil Nadu, in close proximity of the Chennai and Ennore ports. The plant is expected to be operational by 2025-26, and will be manufacturing luxury vehicles in India, which so far were assembled at the Pune plant. “The JLR plant in Chennai is expected to be used for exports to markets such as Australia, Norway and Switzerland, where Indian exports will get zero-duty access,” says Thakkar.

Till a few years ago, auto exports from India were mostly to Africa, Latin America, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Although they are still dominated by Africa and Latin America, new markets such as the Middle East, Europe and Australia are opening up. In March, India announced a new free trade deal with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which includes Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland—countries not in the European Union. The deal was finalised after more than 15 years of negotiations and will remove import tariffs on industrial goods from EFTA states. The agreement entails $100 billion worth of investments across a range of sectors in India, including manufacturing. The EFTA deal followed the signing of trade agreements between India and Australia, and the UAE.

Thakkar adds that some countries within the African continent also want to be seen as a bloc—akin to the European bloc—which eases things like negotiations, infrastructure, bureaucracy and logistics. The ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) region has several countries with auto manufacturing hubs, and therefore presents a lot of competition to exports from India. Therefore, looking at other geographies becomes imperative.

Other export barriers in the past were factors such as vehicles made in India having BS4 emission norms while developed nations like the US having Euro VI emission norms. In 2020, India implemented BS6 emission norms, which are almost equivalent to Euro VI norms. Last year, the government launched the Bharat New Car Assessment Programme, to provide safety ratings to cars made in India. Along with making passenger vehicles safer for Indian roads, these ratings are also meant to make India-made vehicles more saleable in foreign markets.

(This story appears in the 01 November, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)