The big boys of petrol have shocked the EV world with their electrifying performance.

The big boys of petrol have shocked the EV world with their electrifying performance.

The leaders were sluggish in slipping out of the ICE (internal combustion engine) age. While Bajaj and TVS ambled into the EV (electric vehicles) party with Chetak and iQube, respectively, in January 2020, Hero—the biggest two-wheeler player in volumes—made a slow-motion entry with Vida in October 2022. EV, decried analysts and auto pundits, was not a game for heavyweights of the petrol two-wheeler industry. The incumbents—Hero Electric, Okinawa and Ampere—were well entrenched by FY21, and by FY22 they beefed up their presence by capturing close to 60 percent of market share.

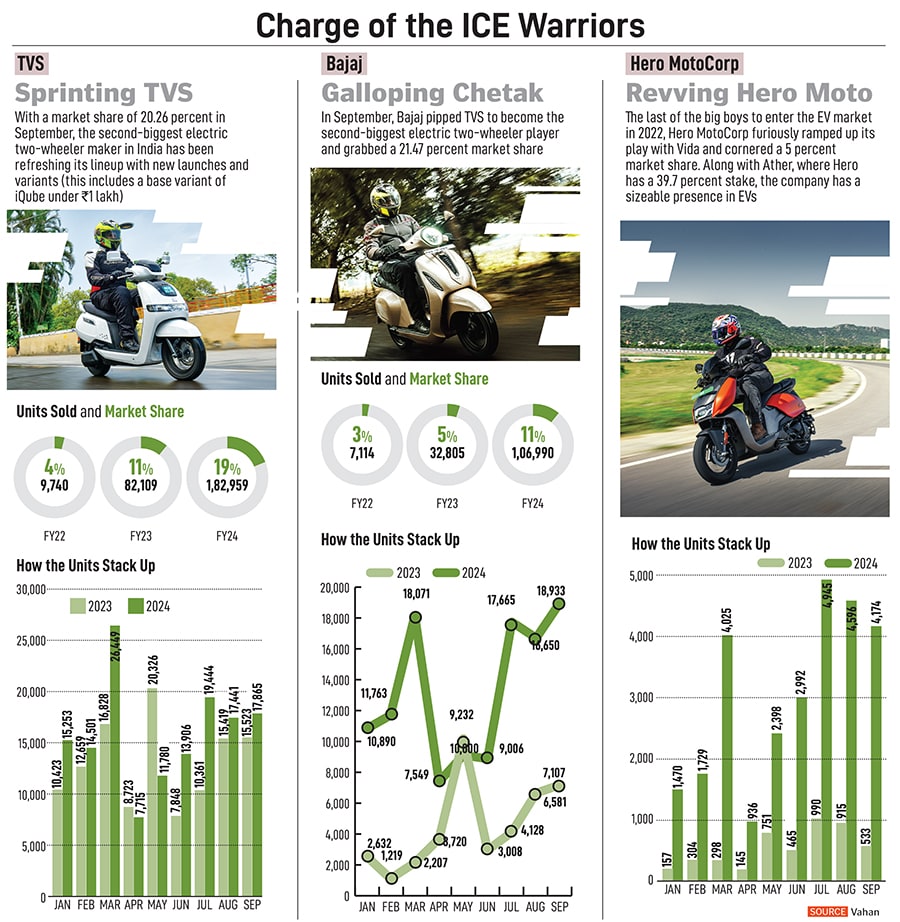

The legacy players, in contrast, were stacked against formidable odds. Just two months after their rollout, Chetak and iQube reportedly clocked sales of 91 and 18 units, respectively, in March 2020. Twelve months later, the collective numbers stomped from two digits to three digits. Chetak remained stagnated at 90 and iQube inched to 355 units. In FY22, Bajaj had a 3 percent market share, TVS was a shade ahead with 4 percent, Ola Electric had cornered 6 percent, and Hero—which had been piggy-riding on Ather—was yet to launch its EV brand. In EVs, the three big boys—Hero, Bajaj and TVS—were pale shadows of their dominating might in petrol two-wheelers.

Fast forward to October 2024. The big boys of petrol have shocked the EV world with their electrifying performance. TVS has become the second-biggest EV two-wheeler player with iQube and has pocketed a 19 percent market share in FY24. In September, it increased its share to 20.26 percent. Bajaj has emerged as a No 4 brand with Chetak and has scooped 11 percent market share in FY24. In September, it pipped TVS to become the second-biggest EV maker and grabbed a 21.47 percent market share. Hero MotoCorp, which entered the EV market with Vida in late 2022, has raced to grab a 5 percent share in FY24. If one adds the market share of the third-biggest EV player, Ather, where Hero has a 39.7 percent stake, the combined clout of both players stands at 17 percent.

“They came, they saw, they kept quiet and then they captured,” reckons Amit Kaushik, managing director (India) at Urban Science International, a Detroit-based global consulting firm. The success of the legacy players, he says, can be attributed to a slew of factors. First, TVS, Bajaj and Hero have spent decades selling bikes and scooters. They understand the dynamics of the market, and decode the needs and aspirations of the buyers. “The EV upstarts and the first movers in the segment underestimated the resilience of the ICE players,” says Kaushik, adding that the legacy players were waiting for the right time to amplify their play.

The second big factor was the long-term play of the big boys. Over the last decade, the EV market has seen a significant froth in terms of a bunch of players who were importing EVs from China and selling in India. Most of them were price warriors who had turned EVs into a commodity game because of the low-entry barrier. “The casual approach led to an unprecedented casualty in terms of poor quality of the product,” says Kaushik. The absence of R&D and in-house development led to heavy dependence on imports, perpetrated a lack of differentiation with me-too offerings, and cooked a recipe for disaster.

A glaring absence of after-sales service, poor charging infrastructure and alleged misuse of government subsidies compounded the woes of most of the players. Hero Electric, the biggest EV player that had a dominant 27 percent market share in FY22, has now become a fringe player as its market share crashed to 1 percent in FY24.

Okinawa slipped from 19 percent to 2 percent, Ampere tumbled from 10 percent to 6 percent, and the market share of ‘others’—the ones importing from China and rebranding in India—skid from 20 percent to 8 percent during the same period. “The big boys played a patient game and were ready to fill the gaps,” says Kaushik.

KN Radhakrishnan of TVS Motor attributes the success of iQube to razor-sharp consumer centricity. “On the overall EV strategy, we always look at the customer,” the chief executive officer underlined in their Q4FY24 earnings call in May. An unambiguous consumer insight was that a user needed multiple options in EV in terms of battery capacity, range and price combination. “Our objective is to delight the customer,” he said, adding that the company took a calibrated approach of expanding across the country, building EV infrastructure, including after-sales services, and building a brand. “We believe that it is more important to build the brand in a big way, and we are on the right track,” he maintained.

Also read: Ultraviolette: Building a performance EV bike in India for the world

Resisting the temptation to play the volume game helped the big boys. When asked about rivals playing the price and discount game, Radhakrishnan remained confident of the strategy of staying away from the herd. “Pricing is only one element in the process of buying,” he reckoned in an earnings call in January, and outlined a slew of other consideration sets: Product, experience, usage, connectivity, infotainment and range.

Bajaj, too, is reaping the rewards of playing a long-term game. Rakesh Sharma, executive director of Bajaj Auto, outlined the EV strategy of Chetak in the first quarter earnings call in July 2022. There were three objectives in the early phase of Chetak. First was the development of the Chetak brand. “It should be a preferred choice of the customer in at least 100 cities, based on product performance and ownership experience,” he maintained, adding that the company is not in the game of chasing volume. A strong service network, he reckoned, would play a big role in assuring customers in the nascent EV category. The goal is to have an elegant and well-performing product. The second objective was to develop strong R&D and supply chain capabilities. The third plank is to expand the product portfolio.

Cut to September 2024, Chetak has done well in executing its plan. “Chetak is now solidly in the number three position,” Sharma claimed in another earnings call in July. While the company has been slowly and steadily building ingredients for a sustainable EV business, what has turned out to be a catalyst is finding the sweet spot in pricing. “This (an uptick in market share) was largely powered by the new Chetak 2901, launched at a price range of ₹96,000 to ₹1 lakh,” he outlined to analysts.

The gambit of trimming the price helped Bajaj attack the sub-₹1 lakh segment, which is almost 50 percent of the EV two-wheeler market. Second, it helped widen the distribution. “We were in 250 stores in June and should be in 1,000 by September,” Sharma outlined, adding that Chetak happens to be the only player to have a metal body, and an onboard charger, has wooed the users.

A high-quality product under a price tag of ₹1 lakh also helped Bajaj in mopping up business from a clutch of smaller players, which earlier had 45 to 50 percent of the market but have now shrunk to over 15 percent. “The rise in Chetak market shares over the last 12 months has been pretty impressive,” he added, and shared the growing ambition of the brand that toppled TVS to become the second biggest in September. “Our next stop is the number 2 position. And after that, we will see how to move towards leadership,” he said.

The EV play, reckon auto experts, can be won by only one factor: Customer centricity. “It is quality and after-sales that is going to decide the winners,” says Kaushik of Urban Science International. The new-age startups need to pull their socks on both fronts if they need to keep the big boys away from the prized throne. Take, for instance, Ola Electric, which has seen a dramatic rise in consumer complaints. While the Central Consumer Protection Authority recently issued a show cause notice to Ola Electric over a deluge of consumer complaints, the Ministry of Heavy Industries has reportedly called for an audit of Ola Electric’s service centres. “Hero, Bajaj and TVS were not in a hurry and took their time to step into the EV arena,” says Kaushik, adding that the big boys have an edge over the ones who rushed into the market without preparation. “The big boys are now ready for the final onslaught,” he adds.

(This story appears in the 01 November, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)