Puran Singh Rajput (left), co-founder and COO, with Ankit Jain, co-founder of EF Polymer Private Limited

Puran Singh Rajput (left), co-founder and COO, with Ankit Jain, co-founder of EF Polymer Private Limited

Image: Mexy xavier

Ankit Jain was apprehensive when he went to visit farmers in the drought-prone Sabarkantha district in north Gujarat in early October. His company had been working with farmers in the area in partnership with a seed company, providing them with their water retention hydrogels that reduce the need for irrigation by around 40 percent. But, on the contrary, there had been excess rainfall.

“There had been around 150 percent more rain in the area we had worked in, and during seed production if it rains that much, the farmers have to quickly pull out the seedlings in the fields the next morning,” says Jain, co-founder and chief business development officer of EF Polymer, which produces Fasal Amrit, a super absorbent polymer (SAP) made out of fruit peels that can absorb more than 50 times its weight in water, thus increasing water retention in soil.

Jain needn’t have worried. While the crop in other fields in the area didn’t make it, theirs had survived. The farmers explained that when it first didn’t rain, the product helped keep the soil irrigated. “Then it rained so much that it wouldn’t stop. But they said when they would go to empty the fields in the morning, there would be no water, it had increased the soil’s absorbing capacity so much.” The farmers, he says, had not only saved on water but also labour costs for emptying the fields.

The story of EF Polymer began in 2015-16 when founder and CEO Narayan Lal Gurjar’s father lost his corn crop in Kerdi, Rajasthan, due to lack of rainfall and asked Narayan, who was interested in science, to look for solutions. Gurjar, then in class 11, started reading up on the various ways in which water can be saved and though there were solutions like drip watering or sprinklers, they were often expensive and inaccessible. It was then that he came across SAPs and set about making one, using orange and other peels, doing hit-and-miss trials. He applied to get into an IIT, but that didn’t work out, and by the time he joined the Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur (MPUAT), he had a working prototype.

The story of EF Polymer began in 2015-16 when founder and CEO Narayan Lal Gurjar’s father lost his corn crop in Kerdi, Rajasthan, due to lack of rainfall and asked Narayan, who was interested in science, to look for solutions. Gurjar, then in class 11, started reading up on the various ways in which water can be saved and though there were solutions like drip watering or sprinklers, they were often expensive and inaccessible. It was then that he came across SAPs and set about making one, using orange and other peels, doing hit-and-miss trials. He applied to get into an IIT, but that didn’t work out, and by the time he joined the Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur (MPUAT), he had a working prototype.

“I had no idea about business or entrepreneurship, but my professor asked me to come up with a business plan so that the product can be researched further and validated,” says Gurjar on a call from Okinawa in Japan where he is currently based. All through school whenever he had a problem, he would reach out to Puran Singh Rajput, his senior in the village. Gurjar once again turned to Rajput, now working in Udaipur, for help with presentations. Later, on his way to make a presentation in Jaipur by train, he ran into Jain. “He turned out to be a junior in my college and was interested in the idea and immediately pitched in at Jaipur.” The three of them went on to found EF Polymer in 2018.

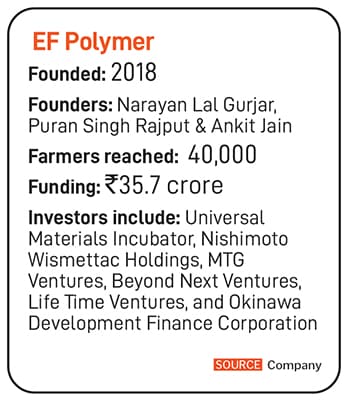

In 2019, their startup was one of the two selected from around the world for the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology’s accelerator programme in Japan. “I was still in second year, and I thought I would complete the degree later, but I shouldn’t lose this opportunity,” says Gurjar. The programme didn’t just come with a financial grant but also offered state-of-the-art R&D facilities, which would help them hone the product and validate it not just in India but also in Japan. Rajput quit his job and the two moved to Okinawa, going on to incorporate the company in Japan as well and raising seed funding of `2.7 crore from MTG Ventures and Beyond Next Ventures in 2021, and later `33 crore in a Series A round in 2023. Investors included Universal Materials Incubator, Nishimoto Wismettac Holdings, MTG Ventures, Beyond Next Ventures, Life Time Ventures, and Okinawa Development Finance Corporation.

Narayan Lal Gurjar, founder and CEO, EF Polymer

Narayan Lal Gurjar, founder and CEO, EF Polymer

“EF Polymer’s product is a 100 percent organic SAP derived from completely natural raw materials and is the only SAP in the world that is certified organic in Japan, Europe and the USA,” says Juichiro Yamaguchi, partner at Universal Materials Incubator Co Ltd. “Their products are low-cost, accessible from emerging countries for sustainable agricultural harvests and, as a result, have the potential to solve food shortages for people around the world. We’ve invested in EF Polymers because we saw an opportunity for significant growth while contributing [to solving] the food-shortage problem in the world.”

Extreme weather events such as droughts and floods are a major risk to food security and have globally led to governments and farmers try resilient cropping methods, to not only protect yields but also farm incomes.

EF Polymer’s manufacturing unit in Udaipur currently produces 100 tonnes of polymer a month and has an expandable capacity of 5x without any major investment, says Rajput, co-founder and COO of EF Polymer. They are present in five states in India—Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat—but have partners almost everywhere, “so you will find farmers in almost all the states who have used our product”, he adds. In order to reach out to and gain the trust of farmers, they have often tied up with foundations and trusts like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Tata Trusts, BAIF Foundation and Social Alpha, while their other partnerships include associations with companies such as Organic Tattva as well as multinationals who source produce like potatoes through contract farming.

Also read: PI Industries: Focusing on small details to win big

Kavita Paliwal, a farmer from Lakhawali village near Udaipur, who has been using Fasal Amrit for one and a half years, says besides saving water, she has been spending less on fertiliser while getting better yields

Kavita Paliwal, a farmer from Lakhawali village near Udaipur, who has been using Fasal Amrit for one and a half years, says besides saving water, she has been spending less on fertiliser while getting better yields

In Japan, points out Gurjar, they are present in two prefectures, and are also set to open an office in the US, where they are working with agriculture universities like the University of California and in Georgia, Texas and Nebraska to validate their product with different crops. “In Okinawa, which is a small island and a tourist destination, soil erosion happens when it rains a lot, which destroys corals, and tourism too gets affected. So even in that, our polymer has helped. Farmers grow sugarcane quite a lot here, so they use our product, and soil erosion has reduced, and we are seeing the impact,” says Gurjar, adding that they have already seen around 4x sales growth this year over sales in the whole of last year.

Expansion to Europe is also on the cards. “We have already started shipping our product to France, Italy, Spain and Portugal,” adds Rajput. According to the company, they have reached 40,000 farmers overall so far, and to support the expansion, a Series B round is planned for March next year.

Besides continuing with research and development to diversify the agriculture potential by using other waste materials like sugarcane, coffee or rice husk waste, “so that we can have a unit close to wherever this sort of waste is available”, the company is also diversifying into using the SAP for products like ice packs—it has collaborated with Iwatani Corporation for this. It is also tying up with cosmetics brands for their “recently launched cosmetic grade product, which they can use to produce eco-friendly, organic and sustainable cosmetic products”, the founders say.

Most makers of SAPs, which are used in products ranging from diapers to sanitary napkins, use synthetic materials but the fact that Fasal Amrit is completely organic and biodegradable means it also nourishes the soil, reducing the need for fertiliser too by about 15 to 20 percent. And it is agriculture that remains their core and vision.

“Our main vision to start this company was to solve the water problem for farmers, to prevent them losing their money due to drought. And to do it in a sustainable way, to align with nature and climate change,” says Gurjar. And even in the future, he adds, the goal remains “to reach the maximum number of farmers”.

(This story appears in the 15 November, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)