(File) Rohit Bal dances as other designers watch during the final presentation of Autumn-Winter 2015 collections at the India Fashion Week in New Delhi late March 29, 2015. Image: Chandan Khanna / AFP

(File) Rohit Bal dances as other designers watch during the final presentation of Autumn-Winter 2015 collections at the India Fashion Week in New Delhi late March 29, 2015. Image: Chandan Khanna / AFP

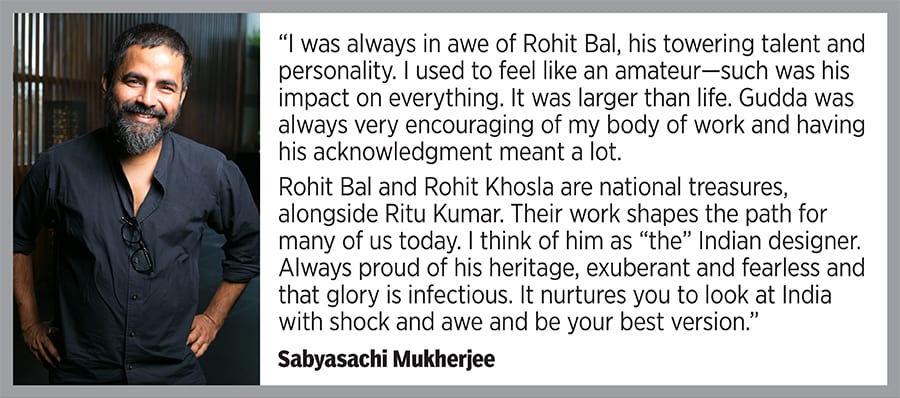

Rohit Bal had already been launched at Ensemble when I joined the company [in the early 1990s], and my earliest memory of him, honestly, is of these stunning Bolero jackets. At Ensemble, we had racks and we had T-stands, and we would have six of these Bolero jackets on the T-stands, they were such a beautiful, niche product—don’t forget that Indian fashion was also evolving at the time.

It was all so new, so experimental. At the time, designers were still very much on the Western format. If you look at what Rohit Khosla was doing then, he had these zebra-printed skirts and capes, with ostrich feathers; even Tarun [Tahiliani] was yet to fully move into the Indian zone. But ‘Gudda’ [Rohit Bal] was the first to really just embrace Indian silhouettes.

He adored the anarkali, loved the jacket shape. He used volumes of fabric in each kurta—really, volumes. He used Indian fabrics, and his sensibility was completely Indian. He used tons of mulmul. Lotuses were his favourite motif. He loved birds. I’ve never seen a silver Swarovski on a Rohit Bal, ever. He was just wildly Indian.

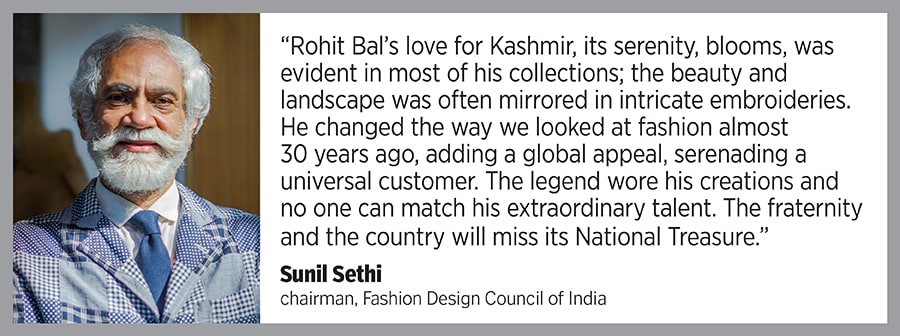

Gudda was a showman, and he loved what he did. With most designers, when their shows are on, they are at the back, draping each model as they walk out. But with Gudda, there wasn’t that much draping. It was a voluminous kurta with a jacket, or a voluminous anarkali with a Bolero and some headgear. There were birds, flora, fauna; there were rich velvets, beautiful garnets, deep, Prussian blues. It was just heady. He was Kashmiri and so proud, and so much of what he made, from the silhouettes to the motifs, would be a love letter to his roots.

Actor Ananya Panday with designer Rohit Bal on the ramp during the grand finale of Lakme Fashion Week, in New Delhi, Sunday, Oct. 13, 2024. Image: PTI Photo

Actor Ananya Panday with designer Rohit Bal on the ramp during the grand finale of Lakme Fashion Week, in New Delhi, Sunday, Oct. 13, 2024. Image: PTI Photo

At his fashion shows, since there was no draping for him to do, he would just be standing with the crowd, watching his models, and you could see just how happy he was. He would be glowing, it would really just be oozing out of him. And when it came to the final line-up, he never walked down the ramp—he only danced.

I remember one of his shows in 1992. It was the first time I saw Gudda’s show, and my jaw dropped. In 1993, he showcased his gall and gumption—at that time, Arjun Rampal and Milind Soman were the hotter-than-hot Indian models. People would see them and their jaws would be on the floor, they were that good looking. Before the sequence started, we got this pool of light, and he had these two shirtless boys come out and do a sensuous dance. And there was a literal gasp around the room, before the models started coming out.

Also read: Reimagining the future of fast fashion: Tackling post-consumption textile waste for sustainability

Another time, it was an ode to the rose. He played with roses that were so big, they were honestly like cabbages—and he didn’t do them in reds or pinks. He did them in beige, ecru, muted shades. It was just stunning.

(File) A model showcases a creation by Indian designer Rohit Bal during the final show at Lakme Fashion Week (LFW) summer/resort 2016 in Mumbai on late April 3, 2016. Image: AFP

(File) A model showcases a creation by Indian designer Rohit Bal during the final show at Lakme Fashion Week (LFW) summer/resort 2016 in Mumbai on late April 3, 2016. Image: AFP

I’d say that the special thing about Gudda was that he was one of the geniuses who turned least commercial. He was true to his vision and wanted to make beautiful things. He has to be credited with being the first Indian designer to take menswear seriously. Some might even say that he evolved more in the menswear space. He was also among the first to launch a diffusion line, called Balance. He really was far-sighted.

Gudda was wild, and super generous. The last time I saw him was at his store, and he insisted on bringing along a home-cooked Kashmiri meal. He served it beautifully, and he brought champagne, which we drank in Rohit Bal crystal champagne glasses. It was heady—even his stores were heady. They were over the top, but in a super sophisticated way.

We went for [model] Mehr [Jesia’s] 50th birthday to Sri Lanka, and the dress code was that men dress as women, and women dress as men. Everyone was from the fashion industry and went full-throttle. We showed up for the party and suddenly, a figure emerged from across the lawn, and it was Gudda. I cannot tell you the lengths to which he went with his costume, to every last detail. It’s not like there weren’t other madly creative people in the room—every last game should have been thought of.

But as he slowly made his way across the lawn, it was like an apparition, a UFO. Whatever he did, he did full-throttle, and to his own standards. Even with his clothes, it was all on his own terms of excellence.

(File) A model showcases a creation by Indian designer Rohit Bal during the final show at Lakme Fashion Week (LFW) summer/resort 2016 in Mumbai on late April 3, 2016. Image: AFP

He was fun, he was brilliant, and I believe his foremost legacy is going to be that he spawned an incredible line of young designers. Sahil Kochhar is from his studio, Varun & Nidhika too. I saw that Karan Torani has worked with him. Pankaj of Pankaj & Nidhi was Gudda’s right hand for a long time.

The amazing and beautiful thing about Gudda was the support he showed to his people. Some designers would be sad and sullen when their teams left to start their own labels. But I’ve seen Gudda support each one of his people. He would come for their shows, dance in the audience. There’s no better legacy than labels who have learned at his studio and now take his work forward, in their own styles, of course.

In terms of his work legacy, it’s quality. It’s stunning quilting. Immaculate menswear. It’s regal, royal India in the most sophisticated avatar.

(File) Indian Bollywood actors Siddharth Malhotra (1L), classical singer Shubha Mudgal (2R) and Daina Penty (1R) gesture during a fashion show by designer Rohit Bal at the Blenders Pride Fashion Tour in Mumbai on January 16, 2019. Image: Sujit Jaiswal / AFP

(File) Indian Bollywood actors Siddharth Malhotra (1L), classical singer Shubha Mudgal (2R) and Daina Penty (1R) gesture during a fashion show by designer Rohit Bal at the Blenders Pride Fashion Tour in Mumbai on January 16, 2019. Image: Sujit Jaiswal / AFP

When I looked at his last show, which took place a few days before he passed, I thought that this is true, quintessential Gudda. He was one of those who stuck to his guns. He never felt the pressure to change, to become more commercial. He had been so unwell, but he came back with such a bang—such an ode to quintessential Gudda style. He danced, albeit feebly, and the song ‘Afterglow’ played, which he loved. I picked that up from him, now it’s one of my favourite songs too.

The show was on October 13, 17 days before he passed. To me, that’s how everyone should have a chance to go—doing what you love, until the very end.

Tina Tahiliani Parikh is the executive director of multi-designer store chain, Ensemble.

As told to Pankti Mehta Kadakia