Ragavan Venkatesan, founder and CEO, Digivriddhi

Image: Mexy Xavier

Rambhai and his wife Maniben of Surendranagar district in Gujarat struggled with their dairy business with three buffaloes. Their income was steady but insufficient for a family of four. Adding four new milch buffaloes to their farm helped double their income in a year, but Rambhai had to take a loan to buy them.

Getting loan approval from traditional banks for small dairy farmers like Rambhai is difficult, at times impossible, due to the lack of credit history and other such information that is not available or documented. Digivriddhi Technologies (DGV), founded by Ragavan Venkatesan, stepped in as a bridge between banks and dairy farmers to streamline and simplify the process of loans, payments and insurance.

As a result, processing time of dairy loans, typically 60 to 120 days, has reduced with DGV using farmers’ milk supply data at the collection centres. “The approval of dairy loans via DGV takes 30 minutes and disbursement is done within 72 hours. In addition, the dairy farmer need not travel far to bank branches for the loan application process or for payment of their milk supplies,” says Venkatesan.

In 2019, Venkatesan founded DGV to offer payment solutions to India’s 800 million dairy farmers. Launched with an initial fund of $3.1 million from Info Edge Ventures and Omnivore, DGV is an integrated dairy fintech, insuretech and a marketplace. Working closely with banks and milk societies, DGV assists dairy farmers at four major steps: Payment solutions, loans, insurance and marketplace for buying and selling bovines. It also offers dairy APIs on the Reserve Bank of India subsidiary—RBIH public technology platform.

In 2019, Venkatesan founded DGV to offer payment solutions to India’s 800 million dairy farmers. Launched with an initial fund of $3.1 million from Info Edge Ventures and Omnivore, DGV is an integrated dairy fintech, insuretech and a marketplace. Working closely with banks and milk societies, DGV assists dairy farmers at four major steps: Payment solutions, loans, insurance and marketplace for buying and selling bovines. It also offers dairy APIs on the Reserve Bank of India subsidiary—RBIH public technology platform.

Venkatesan says that through DGV, he aims to double Indian dairy farmers’ income, present a frictionless BFSI experience to Indian farmers and help them reap the benefits of the digital ecosystem India has created. The vision to help dairy farmers of the world’s largest milk producer may look enticing, but it has been an arduous journey for the founder and CEO. Venkatesan’s previous experience of rural banking and closing working for the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) helped. “Being a niche area, it was quite a task to build a business model around dairy alone,” he explains.

The 42-year Bengaluru born has been fascinated with integrating technology-led innovations to introduce financial solutions for rural agri issues. Venkatasan was a founding member of IDFC Bank, where he had set up a rural banking franchise and conceptualised an assisted digital banking platform. While leading the financial inclusion and government payments vertical at NPCI, he co-created the world’s first interoperable biometric payment platforms, Aadhaar Enabled Payment System (AEPS) and Aadhaar Payment Bridge System (APBS). Both AEPS and APBS supported the government’s direct benefit transfer (DBT) initiative.

DGV’s Support

According to Venkatasan, DGV’s unique phygital approach to solving the entire BFSI for the dairy ecosystem has brought the best of both worlds for them. “Dairy provides the best avenue to increase their disposable income. We first identified the cost and delay in accessing payments to milk farmers and simplified the payment value chain through DGV Pay. Then we started addressing the basic banking needs and customised savings accounts for farmers and current accounts for milk societies,” he says.

DGV Pay is simply the savings accounts for dairy farmers and current accounts for dairy cooperatives. Payments and collections are processed at micro-ATMs set up at milk collection points. DGV Pay digitises cash flows of dairy farmers with the flexibility to withdraw cash whenever required.

With a customer base of one lakh dairy farmers and 1,000 dairy micro enterprises, it has partnered with dairy processors. Dairy processors include NDDB Dairy Services (NDS), Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (Amul), Andhra Pradesh Dairy Development Cooperative Federation Limited (AP Amul) and private dairy companies like Creamline and Sid’s Farm.

With a customer base of one lakh dairy farmers and 1,000 dairy micro enterprises, it has partnered with dairy processors. Dairy processors include NDDB Dairy Services (NDS), Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (Amul), Andhra Pradesh Dairy Development Cooperative Federation Limited (AP Amul) and private dairy companies like Creamline and Sid’s Farm.

DGV Money offers dairy loans and insurance, while DGV Connect is the marketplace for bovines. “Through DGV Money, we simplified digital diary loans and insurance for milk societies and farmers. The direct integration with Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) across the dairy value chain DGV created a unique underwriting mechanism to facilitate digital dairy loans for the dairy farmers,” explains Venkatasan.

DGV also introduced a unique muzzle identification and health scorecard using AI/ML (artificial intelligence/machine learning) for bovines as these animals were, at times, interchanged by dairy farmers to avail loans or insurance. “This identification method mostly helped banks to cut down on delinquencies for loan or insurance purpose, often leading to bad assets,” he adds.

Also read: Meet Indiagold, the Zepto of gold loans

Cash Cow?

The company hasn’t been able to break even yet. In FY24, its revenue was below ₹2 crore, while losses had accumulated from the previous fiscal. However, Venkatasan is confident that the company will earn profits in three years. “We are leveraging all policies and White Revolution 2.0 is going to help create another 200,000 milk societies across the country. The idea is to double the number of last-mile milk procurement points and have them within the reach of every village,” he says.

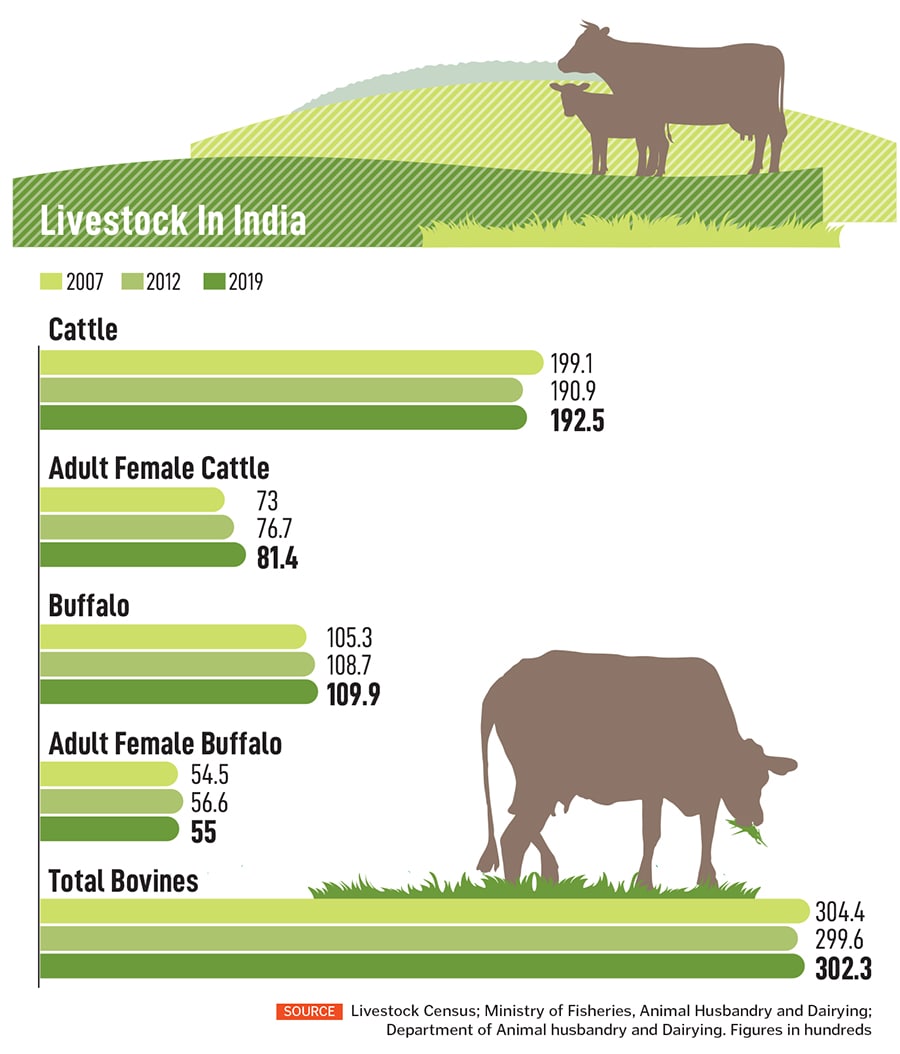

In September, the government launched White Revolution 2.0 which focuses on four key areas—empowering women farmers, enhancing local milk production, strengthening dairy infrastructure and boosting dairy exports. “This will mean more milk collection, more dairy farmers, and as a result, the need for specialised BFSI will increase even more,” Venkatasan says.

The rural financial expert feels the pain points in the dairy fintech business are laden with issues that may be slowing down the business growth. For instance, onboarding with a bank takes more than a year, then creating, designing and launching of a new product takes an average of 10 months with a bank. Even integrating with a dairy processor takes at least six months.

Currently, DGV is operational in three states—Gujarat, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh. By the end of FY25, it plans to expand to Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

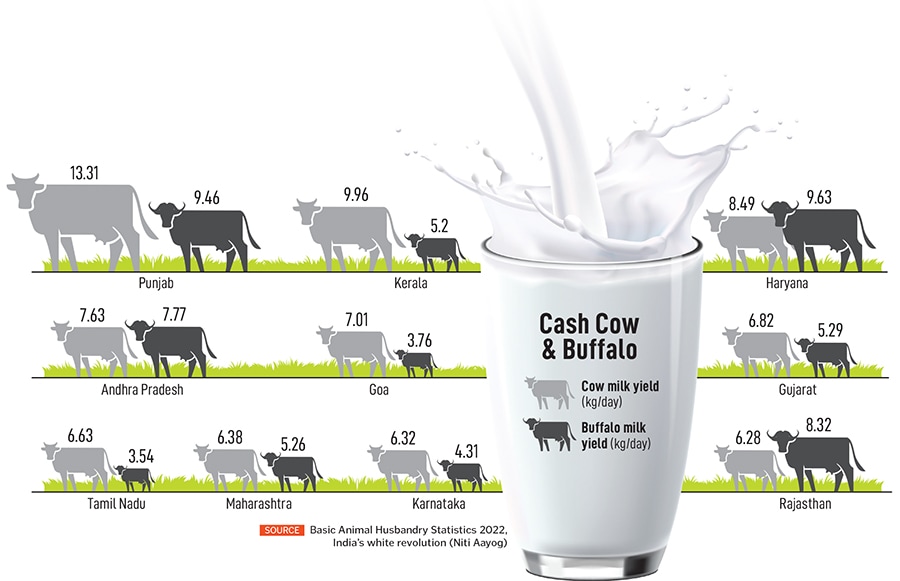

“DGV is doing revolutionary work in the dairy fintech sector. With Venkatesan’s experience in rural banking, DGV is in able hands, providing financial services in the underpenetrated space. We feel the dairy economy has a lot of potential, with India accounting for 24 percent of the total world milk production and 4 to 5 percent of India’s GDP,” says Reihem Roy, partner, Omnivore.

New Horizons

Currently, DGV partners with Federal Bank, Karnataka Bank, HDFC and Bank of India. It aspires to get an NBFC licence by the start of FY26.

It is introducing sub-variants of dairy loan products for deeper penetration, adding categories on the marketplace and at the same time expanding its footprints to new states. “Expanding our services and going international to continents like Asia and Africa would be our second goal,” he says.

DGV caters to small and marginal dairy farmers with two or three milch bovines with an average dairy income of ₹1 lakh and above. Primary asset classes, which it aims to grow in the next 12 months, are digital bovine loan (25 percent of assets under management or AUM), digital dairy maintenance loan (50 percent of AUM) and digital dairy equipment loan (25 percent of AUM).

So far, DGV has raised nearly $10 million. In December 2023, it raised $6 million in a Series A fund by Omidyar Network India. By March 2025, it aims to raise pre-Series B funding worth $10 million.

Crisil estimates India’s dairy industry to see a revenue growth of 13 to 14 percent this fiscal, as strong consumer demand continues along with improved supply of raw milk. Rise in raw milk supply will also lead to higher working capital requirements for dairy players.

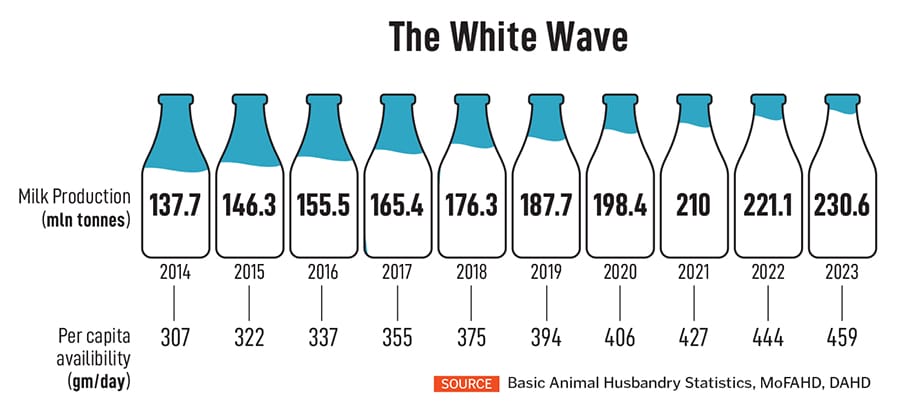

India’s milk production has grown at a 6 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR) with rise in production to 230.58 million tonnes in 2022-23 from 187.30 million tonnes in 2018-19. Milk production of India is estimated to reach 236.35 million tonnes in 2023-24, registering a growth of 2.5 percent over the last year, beating the world average growth rate, as per FAO Dairy Market Review.

(This story appears in the 15 November, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)