From left: The tiger, India’s wildlife superstar, on a safari through Satpura National Park, designated as India’s first biosphere reserve in 1999; ;

From left: The tiger, India’s wildlife superstar, on a safari through Satpura National Park, designated as India’s first biosphere reserve in 1999; ;

Image: Courtesy Charukesi Ramadurai; tiger : Shutterstock

It is late February and winter is almost over, but there is a nip in the morning air that makes me shiver as I walk towards Madhai jetty to take a motorboat for the short ride across the Denwa river. On the other side lies the vast expanse of Satpura National Park spread over 2,133 sq km, an open secret in the south of Madhya Pradesh treasured by hardcore nature and wildlife enthusiasts all over India.

After having visited more than a dozen national parks in India, including Kanha, Bandhavgarh, Tadoba, Ranthambhore, Bandipur and Corbett, I have learnt not to focus on tiger-centric activities, and instead embrace the jungle ecosystem, enjoy the stillness and silence as much as the chattering of birds and the scampering of smaller mammals.

But the heart wants what it wants, and on this chilly morning it wants desperately to spot a tiger within the spectacular landscape of Satpura, dotted with sandstone hills and gurgling rivers. As the park gates open, our safari vehicle drives in; my excitement fuelled by news of increased tiger sightings in the area.

Tigers are India’s wildlife superstars and yet their numbers had dropped precipitously to 1,411 in 2010. Thanks to the success of Project Tiger, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2023, India is now one of the few places in the world with tigers in the wild, with robust sightings in many tiger reserves. The latest tiger census report, released in 2023, says there are over 3,100 tigers across national parks, with the highest numbers in Madhya Pradesh.

However, this has also meant an increase in the crowds thronging the more popular tiger destinations such as Ranthambore and Bandhavgarh. In some of the other parks I have visited, the sounds of the forest have to compete with the chattering of excited humans and roaring jeeps. But not here in Satpura, where a maximum of only 30 vehicles are allowed on each safari. And thanks to the low-key nature of the park, there are rarely more than a handful of them at any time.

Also see: International Tiger Day 2023: Witness the fierce beauty of the jungle cat

Accompanying me are my husband, an official government guide and Shubham, a senior naturalist from Reni Pani Jungle Lodge, an ecofriendly property where we are staying. As tigers prove to be evasive, we discover the forest has plenty of delightful surprises. Satpura was designated as India’s first biosphere reserve in 1999 owing to its lush abundance of flora and fauna. This tiger reserve is now in the process of being considered for Unesco’s list of world heritage sites, which describes Satpura as a “prime example of a central Indian highlands ecosystem”, with many rare and endemic plants, as well as at least 14 endangered species of mammals, birds and reptiles, including the tiger, leopard, gaur (Indian bison) and dhole (wild dog).

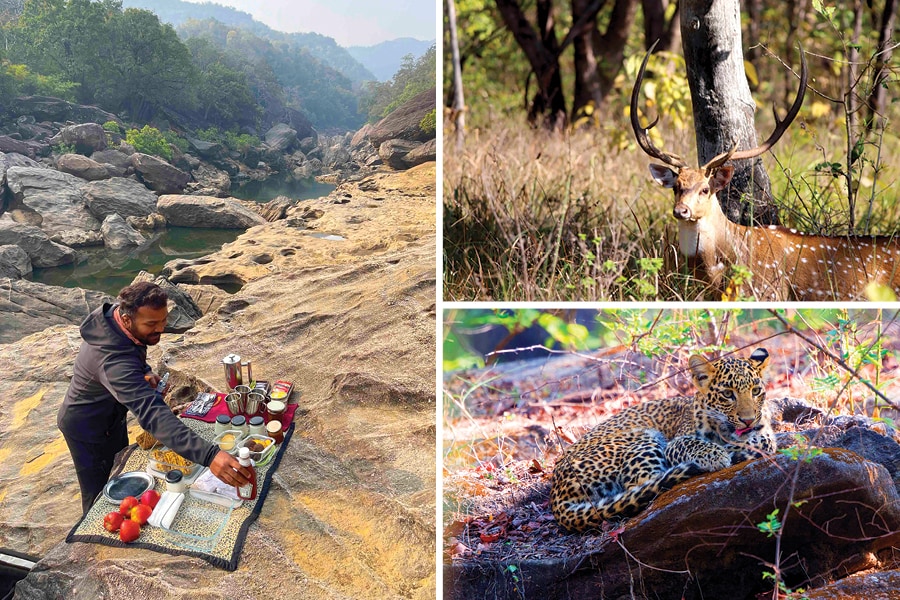

(Clockwise from left ) A picnic at a rocky gorge nestling a clear stream; a spotted deer; and a resting leopard Image: leopard: Getty Images

(Clockwise from left ) A picnic at a rocky gorge nestling a clear stream; a spotted deer; and a resting leopard Image: leopard: Getty Images

Speaking to Forbes India, conservation expert Hashim Tyabji says, “This national park is spread across the highest and most rugged part of the Satpura hills.” He is an old friend of Satpura and originally set up Forsyth Lodge, the first wildlife property in this region; he has worked closely with local wildlife authorities to promote the park in a sustainable manner. “While it presents a challenge for poachers, it is equally a challenge for management. This hilly habitat does not support a large number of prey, which means tiger density also tends to stay low.”

Hotelier and conservationist Aly Rashid, who owns Reni Pani Jungle Lodge and Bori Safari Lodge, says, “Satpura is a mixed forest ecosystem, with montane, riverine and meadow landscapes. The topography is different from other central Indian parks, because it is located within the highest mountain range in central India, with peaks ranging from 250m to 1,450m. This altitudinal variation is one of the main reasons for its rich biodiversity, with varying flora, fauna and birdlife found at different heights.”

Although we are yet to spot a tiger, there has been a significant increase in their numbers in this reserve, up from 13 in 2010 to nearly 65 in 2023, thanks to efficient park management policies that include strict anti-poaching measures as well as a balanced approach to tiger tourism. “Since tourism in this region kept growing, it meant more eyes on the land, and so the management was also forced to become proactive,” Tyabji explains. A firm supporter of ecotourism as an effective conservation tool, he adds, “More people are involved in the business of conservation for their livelihoods—from nature guides to fishermen, everyone is working towards tiger protection now.”

On the ground, ecotourism translates to alternative safari options, such as canoe rides, walking and biking, which don’t use motorised vehicles. This means visitors in Satpura are encouraged to tread lightly on the ecosystem, with minimal disturbance to its wildlife. During safaris, whether in jeeps or on foot, the naturalists and forest guards continuously monitor the forest to ensure its well-being.

For the first hour of our safari, the mist hangs low and thick, making it difficult to see too far. Towering sal and teak trees line the muddy jeep trails, with the fiery palash (flame of the forest) just beginning to bloom in patches. The scene brings to mind poet Bhavani Prasad Mishra’s ode to this beautiful forest: Satpura ke ghane jungal, neend me doobe huey se… [the dense forests of Satpura, as though immersed in sleep].

There is no sign of tiger movement this morning, but as we drive on, Shubham points out various birds and animals: Owlets who wink at us drowsily, brilliantly hued red avadavats, cheeky langurs and docile chital, furry sloth bears and massive gaurs. At a breakfast stop on a rocky shelf high up along the river, we get expansive views of the forest. Satpura is one of the most beautiful forests I have been in.

Apart from the occasional safari jeep, we come across a small group of hikers, accompanied by a naturalist and forest guard. Satpura is the only tiger reserve where walking safaris are allowed within the core zone. Tyabji says, “When I first went to Satpura, it was undeveloped in terms of tourism, and still had a remote and wild feel to it. We suggested the idea of walking safaris to the forest department to promote ecotourism.” Even now, walks are allowed within the Madhai core zone for 2-3 hours in the morning for small groups.

When Satpura did not have many tigers, it was considered safe to allow these walks. And even now, when tiger numbers have increased, these walks continue in the Madhai zone, but with strict supervision from official forest guards and naturalists from the Reni Pani Jungle Lodge (these walks are arranged by the property).

Clockwise from above left: Tribal women work their art on a pitcher; a campfire outdoors at the Reni Pani Jungle Lodge; a view of the earthy, spacious room at the lodge

Clockwise from above left: Tribal women work their art on a pitcher; a campfire outdoors at the Reni Pani Jungle Lodge; a view of the earthy, spacious room at the lodge

Back at Reni Pani—it is named after the purple berries (locally known as ‘ber’) that grow abundantly around the lodge—we relax after the thrill of the morning safari. The lodge is all wood and earth, built to merge into its rustic surroundings and to allow local wildlife unhindered access to various waterholes and hideouts. There are plenty of communal decks on which visitors can kick back with a cooling drink and a book, but no internet since the whole idea is to disconnect from the wired world and reconnect with the natural one.

Tyabji says that, overall, there is a far richer spectrum of experiences available at Satpura, with plenty of activities apart from the traditional safaris. “From guided walks and night drives and boat safaris to camping in the wilderness, there are so many ways to explore this park, and this is what makes it a special place,” Rashid adds. And it is this camping experience that we head out for just after lunch.

Camping under the open sky, in the heart of the forest, is an unmissable experience that Reni Pani offers its guests. For this, naturalist Arvind drives us past villages into the park’s buffer zone, eyes and ears peeled all the way for any wildlife activity. But much like the local people, the birds and animals also seem to be taking an afternoon siesta, and the drive is uneventful, save a distant sloth bear sighting.

At the campsite, where Reni Pani’s team has set up a tent for us, the harsh afternoon sun has given way to a mellower heat and light, and the forest slowly comes back to life. There is also a spacious dining tent, and a small toilet area next to a makeshift shower tent. We sit outside on camp chairs, nursing Mahua Martinis, potent and flavourful cocktails made with liqueur extracted from the native mahua flower, and watching the sun descend onto the horizon, painting the skies pink and purple.

The next morning, Arvind takes us on a walk just as the birds begin their morning chorus, before returning to camp for breakfast, and then back to Reni Pani. I have not seen a tiger or leopard on this trip, but in many ways it has been one of my most memorable forays into the forest ever.