PsiQuantum Co-founders Jeremy O’Brien and Terry Rudolph (left)

PsiQuantum Co-founders Jeremy O’Brien and Terry Rudolph (left)

Image: Nolis Anderson

University of Queensland professor Andrew White could tell his postdoc student had itchy feet. It was 2004, and they had just become the first in the world to demonstrate an “unambiguously entangled quantum logic gate”—the initial step in building a quantum computer. The professor knew he had no budget to keep the student, Jeremy O’Brien, at the university, so he threw a job ad for an academic role in the UK onto O’Brien’s desk.

White got on the phone to a senior professor at the University of Bristol and told him: “I’ve got this great young bloke called Jeremy. I’ll just warn you though, [soon] you’ll be working for him.”

Three years later, O’Brien was building a quantum mini-empire at Bristol that would grow to 100 people, all working on how to build a quantum computer, drawn by its promise of changing the world through incomprehensible computational power.

The Bristol team’s work was spun off in 2016 as Silicon Valley startup PsiQuantum, into which investors poured $665 million, valuing the company at $3.15 billion in mid-2023. It got a whole lot more valuable in April, when O’Brien convinced Australia’s federal and Queensland governments to spend A$940 million ($632 million)—split between equity and loans—for PsiQuantum to build the world’s first useful quantum computer in Brisbane by 2027. Then, in July, PsiQuantum announced the Illinois state government in the US offered $500 million in tax incentives for it to build a second computer in Chicago by 2028, and tipped in another $200 million to build a cryogenic plant to the company’s specifications.

It’s a high-stakes race that puts PsiQuantum in competition with the likes of Intel, IBM, Microsoft, Amazon, the Chinese government and a pack of startups. Because whoever gets there first will be able to charge a bomb for time on their machine that is predicted to do things current computers can’t, such as design complex drugs, streamline traffic flows, crack codes, smash the blockchain and create human-like artificial intelligence. A chance to make history is also on the table for PsiQuantum’s four co-founders—CEO O’Brien, chief architect Terry Rudolph, chief scientific officer Pete Shadbolt and chief technologist Mark Thompson.

O’Brien traces his quantum computing journey to 1995 when, as a 19-year-old physics undergraduate at the University of Western Australia, he picked up a year-old copy of New Scientist. “It described how quantum mechanics is not only whacky, weird and wonderful, but how you could do something incredibly useful if you could get it under control and build a quantum computer,” he says on a video call from Warrington, UK. where PsiQuantum has a research facility. “And I’ve been pretty well hooked ever since.”

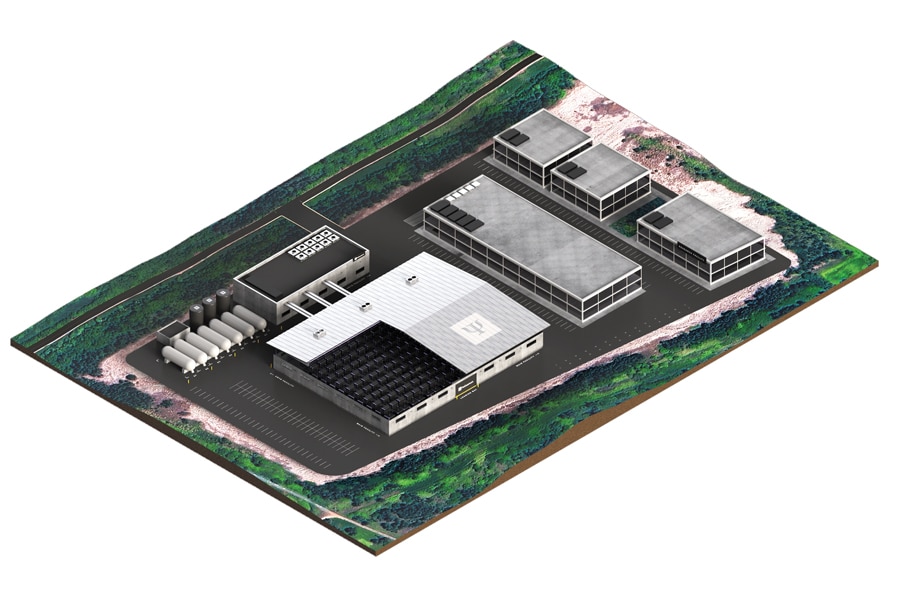

PsiQuantum’s Brisbane site plan

PsiQuantum’s Brisbane site plan

He moved to Sydney’s University of New South Wales to do a PhD. One of his supervisors, Bruce Kane, had come up with the idea for making a quantum computer using single phosphorus atoms in a silicon chip. O’Brien spent the next five years working on that idea but had “a bit of a crisis,” he says. “I just couldn’t see a way that we could scale things up to the million qubits needed to actually bring about this profound impact of the technology.” A qubit, or quantum bit, is the basic unit of information in quantum computing.

But that’s when a team at the University of Queensland with colleagues in the US, figured out a way to use light particles, photons, as qubits. “I managed to talk my way into a postdoc at the University of Queensland with Andrew White, who was setting up a lab to try and pursue this photonic approach, despite me not knowing which end of the laser light came out of,” says O’Brien.

The partnership between White, O’Brien and three others led to the 2003 Nature paper where they successfully demonstrated quantum entanglement with mirrors and beam splitters bolted to a three-meter bench. The scientists had created a quantum logic gate, akin to an enormous transistor. The problem remained of how to turn that into a million-qubit quantum computer. O’Brien wondered if you could combine silicon with the optical approach. He knew he needed somebody who understood quantum, somebody who could design a chip, and somebody who could make that chip.

And that’s when White threw the job ad for Bristol’s Centre of Quantum Photonics on his desk. “I applied on the same day,” says O’Brien. Bristol had the ability to manufacture the components he needed.

Optical engineer Mark Thompson cold-called O’Brien to ask if it was worth his while applying for a senior job on O’Brien’s new team in Bristol. Thompson, a physics graduate, knew nothing about quantum, but he’d had a career in the optics industry and he was looking at what would be the next big thing in photonics. After an 18-month secondment to Toshiba’s silicon photonics research centre in Japan, Thompson returned to Bristol. “We ran with this idea of taking quantum physics and quantum optics and merging them with photonic engineering to create this whole new field,” he says. Thompson thinks they coined the job description “quantum engineer”.

Five years after the first Nature paper, O’Brien’s team published an article in the same publication, taking everything they’d done on a 3-meter, 1-ton bench in a lab and doing it in a silicon chip.

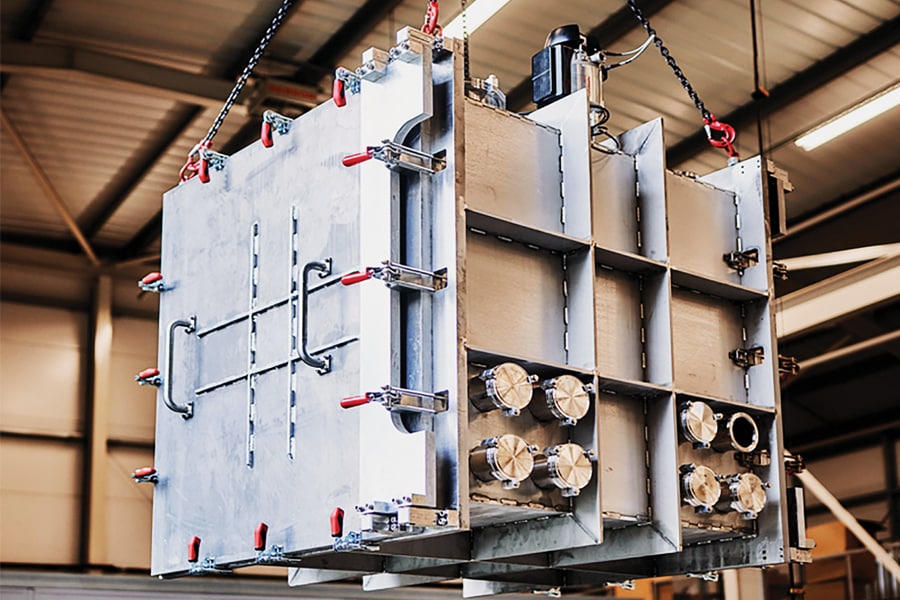

PsiQuantum’s prototype cooling system

Terry Rudolph grew up in landlocked Malawi, southeastern Africa, the son of teachers. At 12, his family migrated to Queensland and he studied physics and math at the university there before going off backpacking. It was only after he had decided on physics as a career that he learnt his grandfather was Erwin Schrödinger, the Nobel Prize-winning Austrian physicist who coined the expression “quantum entanglement” in the 1930s.

In 1995, Rudolph’s backpacking took him to Toronto, Canada, where he started a PhD in quantum optics—the year that the notion of quantum computing took off. “If you’re an early mover in a field,” says Rudolph, “you don’t have to be as good because there are not as many people in it, and there’s lower-hanging fruit to pick.”

That low-hanging fruit got him a postdoc in Vienna with Anton Zeilinger, who won the 2022 Nobel Prize for Physics. From there, Rudolph went to Bell Labs, the American research company behind radio astronomy, transistors and photovoltaic cells (now part of Finnish telecoms giant Nokia).

PsiQuantum co-founder, Mark Thompson

PsiQuantum co-founder, Mark Thompson

Image: Courtesy Forbes Australia

Rudolph took a pay cut to return to academia, moving to Imperial College London in 2003, around the same time O’Brien moved to Bristol, who he knew from the conference circuit. At O’Brien’s urging, Rudolph began to consider how a quantum computer might use light. “Photons are just a very different way of encoding your quantum information,” Rudolph says. “Light is never stopped. It’s always running around. It’s moving fast, so it has things that make it problematic, but then it has things that make it a beautiful way of doing quantum computing.”

Over time, Rudolph grew to know people in O’Brien’s orbit. “He was building an empire, an amazingly large group,” recalls Rudolph. “He was bringing in good people and giving them the resources to do things.”

Also read: QNu Labs: Solving complex problems with quantum computing

One such young person was Pete Shadbolt.

As a kid, Shadbolt had always wanted a Nintendo. “My mum and dad were hippies. They got me a 486 PC and a family friend gave us a copy of Turbo Pascal, a very early programming language, and they said, ‘Write your own bloody video games,’” he says on a call from Palo Alto, California, where PsiQuantum is based. By 17, he’d created Free Rider HD, a a game that allows users to draw their own bike tracks.

At Bristol, he did his PhD under O’Brien. “I was just so lucky to come right at the beginning of what Jeremy was doing. It was a really simple idea: Take these silicon chips from the telecom industry and repurpose them—put a single photon in there instead of a bright laser pulse.” From there, Shadbolt went to London to do his postdoc in theoretical quantum with Rudolph.

Silicon photonics—the ability to switch light in silicon chips—was catching up to the point where they could plausibly make a small quantum computer. But they needed millions, ideally billions, of these switches. With another of Rudolph’s PhD students, Mercedes Gimeno-Segovia, Shadbolt and their team succeeded in 2014. “That [paper] was the foundation for PsiQuantum,” says O’Brien. “We had this architecture that we believed satisfied what I had been trying to do all the way along, like back in the Sydney days: How do we leverage the semiconductor industry to make a quantum computer.”

Crucially, O’Brien met Jeff Brody from San Francisco-based Redpoint Ventures, who put him onto Peter Barrett, co-founder of another Silicon Valley VC firm, Playground Global. Barrett, an Australian, had given Elon Musk one of his first jobs in Silicon Valley at Rocket Science Games, a video game company that Barrett co-founded, and during his nearly 13 years at Microsoft spent time with its founder Bill Gates.

“Jeremy and the team at PsiQuantum are the smartest people I’ve ever worked with—no, seriously,” Barrett says in Sydney. “That company is ridiculous in terms of intellectual horsepower.” O’Brien shook hands with Barrett and Brody In April 2016, raising $13 million to begin the long grind. PsiQuantum was born.

O’Brien, Thompson and Shadbolt were all in as founders, but Rudolph was still skeptical. “I wasn’t going to be a founder at first. I was quite happy in academia. I didn’t need the headache.” O’Brien, however, was not good with ‘Nos’ and kept at him until he agreed. Playground Global’s incubator was PsiQuantum’s first office, with old arcade games, a motorbike collection, amazing food and a fake tree.

Around 2020, they started looking for a place to build the world’s first useful quantum computer. Australia was eager to attract cutting-edge companies, and after years of talks, the federal and Queensland governments agreed to April’s A$940 million deal. O’Brien says that because PsiQuantum’s computer would be around for a long time, his priority was a long-term partnership, where he could be certain of stable government, a well-educated workforce and a thriving economy.

The company will break ground at the site near Brisbane Airport at the end of 2024 or early 2025. There will be two buildings. One is a cryogenic plant that cools helium gas to a liquid and pumps it into the building next door, which will look like a data centre full of cabinets and racks. Rudolph, ever the theorist, can’t wait to get onto the machine and start using it. “The nice thing about this technology is that everyone wants it for its different applications. But one of the things quantum computing will be good for is solving problems of quantum mechanics.”

If they get this working, there will be vast demand for limited time on the machine. Rudolph finds himself in a position to, maybe, jump the line. “But whenever I tell people on the business side of the company this, they say, ‘I hope you’re feeling rich because you’re going to need it to run stuff on this machine.’”

That problem, however, isn’t coming soon. Even if they make their 2027 deadline for finishing the world’s first error-corrected, functional quantum computer, Rudolph says it probably won’t meet his needs. “The things I’m interested in will require huge quantum computers—ten times more than the one we’re building. How long it takes to make that jump? I don’t know.”

This article was adapted from Forbes Australia, a licensee edition of Forbes Media.