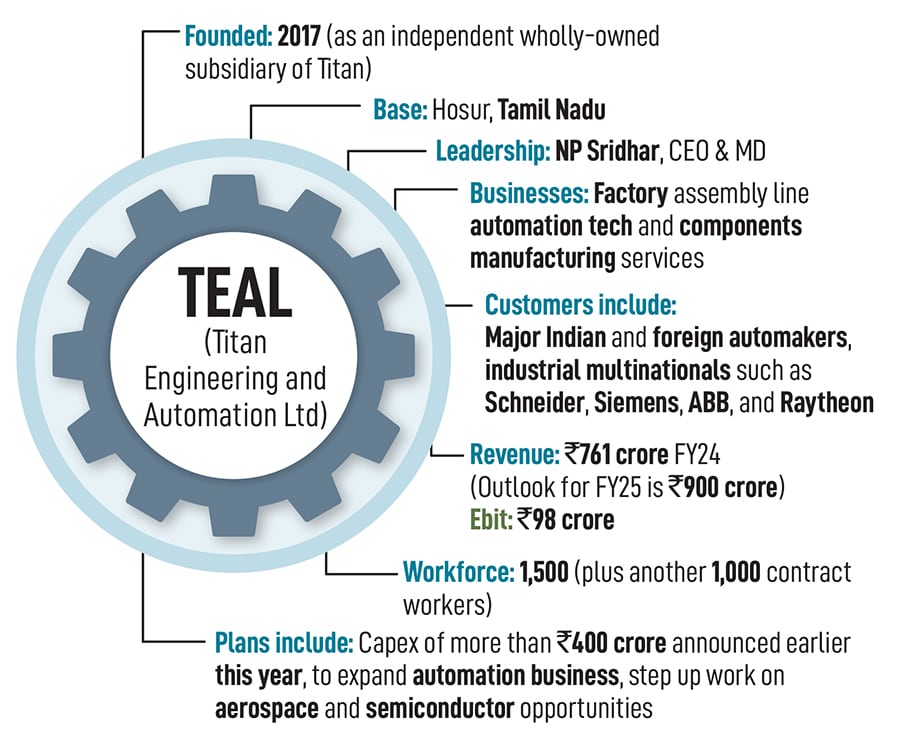

While the Titan Company is well known in India as a watchmaker, with a story that goes back 40 years, its engineering business, its only B2B unit, is less well-known. That unit, Titan Engineering and Automation Limited (TEAL), counts some of the biggest auto companies, for example, in India and overseas as customers using its factory assembly line automation solutions.

TEAL also counts marquee customers such as Raytheon, one of the world’s biggest defence manufacturers but a buyer of components for civilian aircraft when it comes to Titan Engineering’s manufacturing services line of business. TEAL is now making a foray into the semiconductor assembly space.

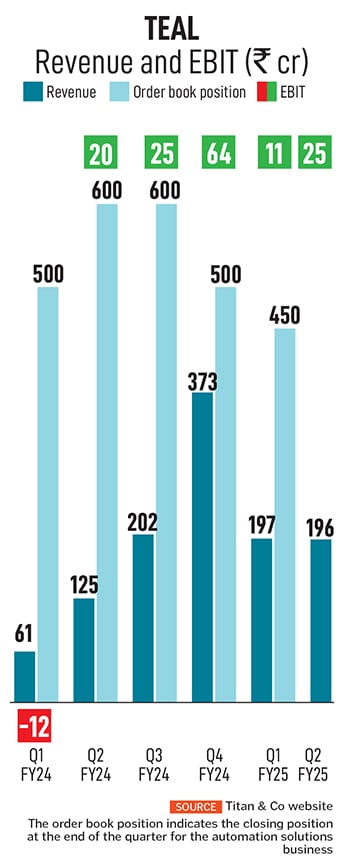

This fiscal, ending March 2025, TEAL is on track to hit ₹900 crore in revenue, profitably, CEO and MD Neelakantan P Sridhar told Forbes India in a recent interview.

The company’s journey started in the 1990s, when a handful of engineers and technicians from Titan’s maintenance division decided they needed to build some of their factory assembly equipment in-house, and that indeed they could. They persevered, and that pilot effort grew into a full-fledged precision engineering division by 2004.

By 2009, they were ready to export a robotic assembly line to the US and, in 2017, the division became TEAL, a company wholly-owned by Titan. Milestones along the way, like successfully building an assembly line for Delphi, an American tier 1 auto components company, helped.

“The beauty of it is, 25 years on, the basic concept of the machine has very much remained the same, but you can get more data out of the machine now,” Sridhar says. “Earlier, we didn’t look at all the data coming from the machine. But now you can have a lot of sensors. You can get a lot more data about what the machine is performing, how it is performing. That has changed.”

The knowhow for micron-level precision naturally led to TEAL exploring adjacent opportunities in manufacturing services (a micron is one millionth of a metre, say about one-tenth the thickness of one human hair.) They started with making some panels for spacecraft. Today “one of our biggest customers is Raytheon Technologies,” Sridhar says.

The engagement started with a contract from Hamilton Sundstrand, he recalls, before it was acquired by United Technologies Corp that, in turn, merged with Raytheon.

Say, one is taking an IndiGo flight on one of its A320 Neo aircraft. When it lands, there is a braking system called after thrusters or reverse thrusters “If you are [seated] in front of that engine, you will see a cowl actually going behind,” says Sridhar. Critical components of that actuation system are built at TEAL.

The assembly of completely automatic assembly lines at TEAL Automation Solutions plant, Hosur

The assembly of completely automatic assembly lines at TEAL Automation Solutions plant, Hosur

Or, on an Air India flight, onboard a Boeing 787, one of the best aircraft for air management systems, “very critical components are built at TEAL”, he adds. The Pratt & Whitney engines that power IndiGo’s aircraft have important components that are made at TEAL, Sridhar adds.

India’s Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) makes a light helicopter, and some of the components that go into its engine are made at TEAL. “So, we have quite a lot of good content that goes inside some of the most popular aircraft on the planet today.”

“We have two businesses that complement each other beautifully,” the CEO further says. The aerospace business is capital intensive, because it demands really high-quality precision equipment. And TEAL has a state-of-the-art facility with more than 130 world-class CNC machines and other gear.

Also read: India’s defense sector: From increased spending to indigenisation

The automation solutions business, on the other hand, is very design-led and calls for extremely competent people in solutioning, while it is capital-lite. With this combination, TEAL has evolved from making small individual components 20 years ago to making entire complex sub-assemblies today.

For example, in the popular A320 Neo aircraft that airlines, including IndiGo, have deployed, the engine is called a geared turbofan (GTF) engine that Pratt & Whitney developed. And the engine has what is called a pneumatic starter—it uses compressed air to get the engine going until it generates its own power.

The key sub-assembly of that starter is built at TEAL, Sridhar says. “When this goes into the line, they just add a few more components and then the starter is built. So we’ve migrated to that extent. But we are [still] in that journey of a greater degree of complexity, higher engineering element in it, putting parts together, building to spec.”

He adds: “Today, we are building to a print, which means the drawing comes from my customer and we build to that. But now, increasingly, we are looking at how we can get specifications from the customer and then design and build to that. That’s the next level that we would want to get to.”

That future is about system integration and built-to-spec.

That future is about system integration and built-to-spec.

On the automation side, TEAL is a leader in supplying assembly lines to OEMS for making everything, from door latches to electric vehicle (EV) batteries. The knowhow also lends itself to other verticals, such as medical devices, electrical gear and so on, with customers such as Schneider Electric, ABB and Siemens.

TEAL will also be making strong forays into consumer electronics assembly and lines for solar panels. And one of its most exciting opportunities is in semiconductor assembly. Initially, this will be at the stage where chips have already been manufactured.

At this point, there are several packaging processes that are more bespoke “which is our play”, he says. For example, once the chips are made, they can go into printed circuit boards. TEAL already knows how to build an automated assembly line for this.

Overall, about 50 percent of TEAL’s automation output is export-oriented. The company has customers in France, the UK, Germany, Sweden, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia. And with respect to North America, Sridhar points out that the decision-making is in the US, but the actual lines will likely be in Mexico, where TEAL has installed lines in multiple cities.

Starting this year, TEAL has stepped up efforts to send its experts to the US as well to drum up more business there. Much of the design work is done at TEAL’s headquarters in the town of Hosur, in Tamil Nadu, a couple of hours by car from Bengaluru. The lines are built, assembled, and tested there. Once they pass muster, the lines are disassembled and shipped to the customers’ sites where TEAL’s team will assemble and commission them.

The company has about 1,500 people on its own rolls and another 1,000 or so on contract.

Sridhar says TEAL doesn’t provide a breakdown of its revenue but its two lines of business are roughly equal, with automation being slightly bigger. Over the next 2-3 years, he expects to spend more than ₹400 crore in capital expenditure to expand TEAL’s two business lines. The money will come from a combination of internal accruals and loans.

Aerospace and semiconductors are two important areas of investment. In two years, TEAL will also look to build its own campus. Automotive will remain a strength, and as electrification kicks in, there will be massive opportunities. R&D investments are also being made in software, machine learning and the application of AI to factory automation.

“We use their machine assembly automation lines across all the three different operations of our manufacturing,” the regional purchasing head of a tier 1 auto components supplier tells Forbes India. The European company has a large operation in India with thousands of employees and the person didn’t want to be named discussing a specific vendor.

TEAL’s solutions have helped the auto component maker meet the key performance indicator standards in its Indian as well as overseas factories, he added, be it automating a basic pick-and-place task or detection and control systems in a line that processes a hundred parts every second.

TEAL has also helped this company design factory layouts and work flows for constrained spaces, he adds.

TEAL has also helped this company design factory layouts and work flows for constrained spaces, he adds.

“One of the deterrent or impediments for Indian suppliers is to take a giant leap in global trading,” the purchasing head adds, who also has a role in the company’s international supply chain. Consider that about a third of India’s $60 billion auto components output was for exports. But that pales in comparison with the nearly $120 billion auto component exports from China.

“The appetite and hunger with which the Chinese [and Korean] players are jumping in the business in terms of speed, the fully developed supply chain ecosystem and then the real project management” is yet to be matched by Indian players, he says. TEAL also needs to quickly establish a much stronger local presence in its key markets, he adds.

The European Union-headquartered company is looking to ramp up its exports by hundreds of millions of dollars, which represents a lot of opportunities for vendors such as TEAL—if they can step up. Second, Indian vendors will have to figure out how to match the efficiency and speed-to-market of the Chinese, he says.

The European Union-headquartered company is looking to ramp up its exports by hundreds of millions of dollars, which represents a lot of opportunities for vendors such as TEAL—if they can step up. Second, Indian vendors will have to figure out how to match the efficiency and speed-to-market of the Chinese, he says.

A third aspect is, with respect to this European customer of TEAL itself, there is enormous scope to get into assembly automation of much higher-value components that involve much more electronics, versus the mechanical products that TEAL currently has a lot of expertise in, he says.

While in countries such as India and Mexico, labour is cheap, automation is on the rise in the rich countries where it is not, the purchasing head points out. Automation density will only increase, he says, with the use of robots and co-bots (collaborative robots), automated material movement and so on.

“There is no better time for automation,” Sridhar agrees. And to see the big picture, one must visit China, he adds, where one can see the “fullest extent” to which automation is possible.

Geopolitical circumstances are pushing most rich countries to bring back manufacturing as close to home as possible, de-risking supply chains. There are investments being made in manufacturing all over the world. “But the fact is that there aren’t too many people in those advanced economies to man some of these factories, so automation is probably the only way.”

And that’s where he sees opportunity for TEAL. It has talent at scale, the ability to build that really well in India, and a good supply chain locally. As automation rises, TEAL can compete not only on the competence of its people and the solutions it can provide, but also on the fact that it can be hugely cost competitive in building from India, he says.

The flip side of the talent story in India is that young recruits aren’t industry-ready, he points out. “They are competent people, but they don’t know their engineering, and we teach them engineering all over again.”

Industry-oriented schools such as Tata Institute of Skilling are doing a good job, but much more will be needed as manufacturing grows in India, he says.

A more difficult challenge, perhaps, is that today, most key automation elements are imported and mostly from China. Companies such as TEAL are grappling with the real possibility of that supply going away for geopolitical reasons. Building the local ecosystem for such components will be critical.