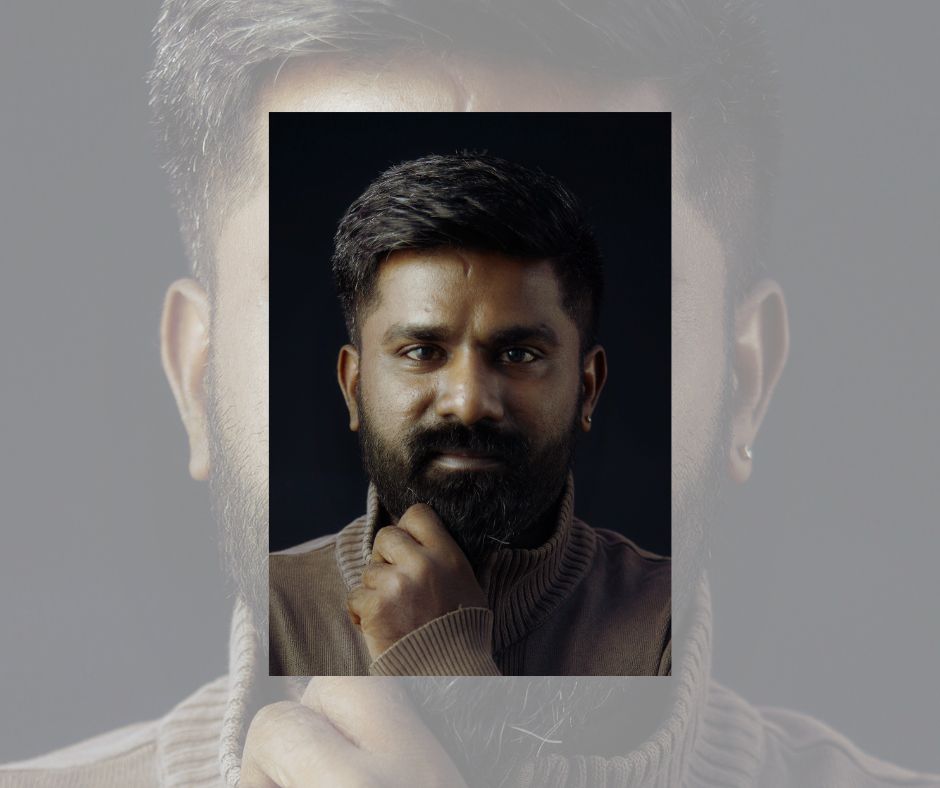

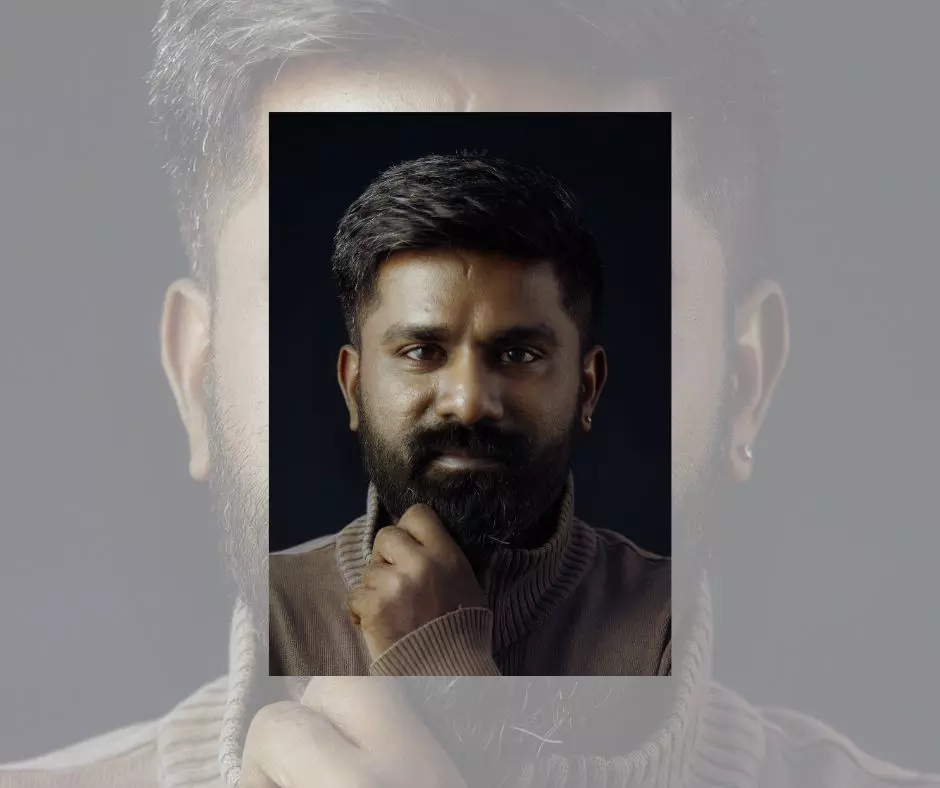

HYDERABAD: The November breeze felt heavier in the presence of photographer Jaysingh Nageswaran, not because of the weight of his words but the sheer honesty with which he spoke. Sitting in the balcony at the State Art Gallery in Madhapur, where his photo essay, ‘The Land That Is No More’ is being featured at India Photo Festival 2024, he spoke while holding his hands loosely together, explaining how photography for him isn’t just about images but about a life that refuses to be silenced.

“I want to tell my stories, so I’m photographing,” he said simply, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world. But nothing about Jaysingh’s life has been simple. Born to a Hindu father and a Christian mother in a small Tamil Nadu village, his childhood carried both celebration and rejection, a sense of belonging and separation. While his parents embraced each other’s traditions, outside their home, there were rules enforced, and boundaries made visible.

As a young boy, Jaysingh watched his grandmother, who is a repeated motif and theme in his photo stories. She was a woman who defied odds of caste-based patriarchy to start a school that still stands today. Known as Ponnuthai Amma Gandhiji Primary School, it was a school built to create a space that was inclusive and open to all but was vandalised in between and a court order finally restored it.

“The entire village came to apologise to us. Now my family manages the school,” he said, speaking proudly. He adds, “Through her, I saw the world.” This Dalit identity, however, meant rejection, which followed him everywhere, from playground hockey teams to the invisible walls that defined village life.

For years, Jaysingh wrestled with this invisible weight. “It took me 25 years to stop being shy, to say, ‘This is my story,’” he admitted, his voice soft but steady.

The Covid pandemic, ironically, became his moment of reckoning. Nowhere else to go, he was forced to turn his lens inward. This led to him photographing the stories of his family, his grandmother’s resilience, and the fragments of his identity he had carried in silence for decades.

His work is deeply tied to memory, both his own and the collective memory of his community. As a child, he lived near a crematorium. At night, the smell of burning bodies would drift through the air as he lay on the terrace under the open sky.

“At first, it was unbearable,” he said, his eyes narrowing as if recalling the intensity of that sensory experience. “But then it became part of me.” It’s this sensory world, the smells, the sounds, the textures, that finds its way into his photographs, into his mode of storytelling. “I don’t just shoot an image; I feel the place, the smell, the light, the air. Only then do I press the shutter,” he said, adding, “I need to feel it to click it.”

When Jaysingh talks about his work with the transgender community, there’s a raw honesty that comes through. “At first, I was afraid of them,” he admitted. “I would hide in the train when they came near me.” But the more he avoided them, the more he questioned his fear.

Coming from a space where rejection and discrimination has been a part of his community identity that he had to fight, he recognised that same alienation mirrored in the lives of Trans people. Over time he broke these biases and evolved to put together The Lodge — a humane, organic and real portrayal of trans lives that earned him the Grand Prix at the Kyotographie International Photo Festival in Kyoto, Japan. “This work taught me to be fluid — not just in how I see gender, but in how I see humanity.”

Speaking on the philosophy behind his art and what he expects of young photographers, he said, “You can’t plant a seed today and eat the fruit tomorrow.” While the world races for likes and followers, Jaysingh lets the stories come to him, unforced and authentic. “Do what you feel,” he advises young photographers. “Not for likes, not for someone else.”

His grandmother’s school, his Dalit heritage, and the smells of burning wood at the crematorium are all part of the story he carries forward. But it’s not just about the past — it’s about the resilience to build on it. “If I had a knife, I might have used it to fight,” he said, quoting the American photographer Gordon Parks. “But I have a camera. So, I use it to tell my story.”

Jaysingh doesn’t romanticise his journey, nor does he sugarcoat it. “It’s not easy,” he admitted. Even today, speaking about his work sometimes brings him to the brink of tears. But he holds back, not out of repression, but to give space to the stories themselves. For him, photography is less about the technicalities of light and composition and more about being present, about letting the moment reveal itself.

Jaysingh hesitated when asked why he takes pictures. Finally, with the weight of someone who has battled for that sensation his entire life, he answered, “To feel human.” Long after he finished speaking, his words lingered in the still balcony. The story of Jaysingh is not unique to him; it is a universal tale of perseverance and reclaiming one’s identity in a society that frequently tries to define it for you.