Generative AI stands to make workplaces more efficient by automating busy leaders’ routine tasks—such as the electronic communication that takes 24 percent of a CEO’s time, studies show.

Generative AI stands to make workplaces more efficient by automating busy leaders’ routine tasks—such as the electronic communication that takes 24 percent of a CEO’s time, studies show.

Image: Shutterstock

If a chatbot can Slack convincingly in the boss’s voice, will employees follow orders once they realize the CEO is actually a machine?

A novel two-part study finds that an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot trained to write like a technology company’s CEO responded to questions so believably that many employees thought the answers came from the boss himself. But there’s a caveat: When employees perceived that a response came from AI—even if it didn’t—they rated those responses as “less helpful” than those they thought came from the CEO, demonstrating a classic case of “algorithm aversion.”

It’s an AI-age twist on the classic Turing Test, developed by British computer scientist Alan Turing in 1950 to judge whether machines could exhibit “intelligence.” Called the “Wade Test,” after the CEO of the company the researchers studied, the analysis is among the first to showcase AI’s ability to replicate the unique characteristics of a specific person’s writing style, says Prithwiraj Choudhury, the Lumry Family Associate Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

“We trained an algorithm to write using the same words and phrases and punctuation meter and grammar and mistakes and abbreviations the CEO uses,” Choudhury says. “What that tells us, generally, is that at least technologically, we can create a writing bot for any one of us.”

Generative AI stands to make workplaces more efficient by automating busy leaders’ routine tasks—such as the electronic communication that takes 24 percent of a CEO’s time, studies show. In theory, this would allow the executive to devote more time to strategic planning, for example. Yet the new research indicates that there’s still a long way to go before humans cede the craft of writing to machines—if that ever happens in an organizational context.

Overcoming aversion “is the billion-dollar question in front of the AI industry,” says Choudhury, who teamed on the paper with Bart S. Vanneste, associate professor at University College London’s School of Management, and Amirhossein Zohrehvand, assistant professor at Leiden University.

Turing, meet Wade

The Turing Test is an imitation game in which a person must guess whether they’re communicating with a machine or another person; if their success rate is no better than random chance, the machine wins.

The three researchers worked with an unnamed, 800-employee technology company to construct a new game that imitated a specific human: the company’s CEO. They designed a field experiment to assess the potential for AI to assume aspects of a CEO’s communication responsibilities.

Choudhury and his team built a “CEO Bot” by providing a large language model with all internal and external communications from the real boss, including emails and Slack messages. The idea was to create a machine “stand-in” that could answer questions using the CEO’s specific writing preferences, conventions, and peculiarities.

Also read: What happens when business owners turn to chatbots for advice

Ask me anything

The researchers then chose 10 real questions from a pool of 148 that came from new hires at a recent “ask me anything” session and put them to both the CEO and the CEO Bot. All 800 employees were invited to participate in the study, with 105 accepting the challenge: To identify which answers came from AI and which came from their CEO. Of that group, roughly 90 percent had worked for the company for three or more years.

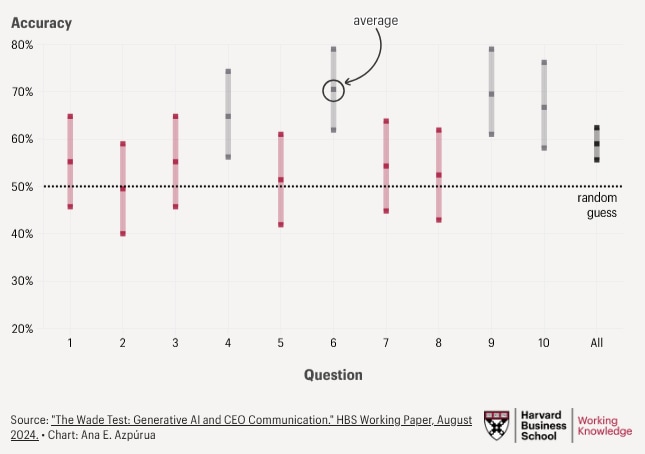

Employees answered correctly 59 percent of the time—a notable result, Choudhury says, given that random guessing would result in an accuracy rate of about half. Broken down into categories, employees correctly identified 61 percent of the real CEO’s answers and 57 percent of the AI’s synthesized responses.

Who wrote this? Employees struggle to tell CEO from AI

In six of 10 questions, workers identified the message origin with the same accuracy as random guessing (50 percent). Their overall accuracy rate was 59 percent.

The significance, Choudhury says: “The real employees of the CEO, the folks who know the CEO well, cannot identify which answer came from the human and which came from the bot.”

Personal communication chatbots

The experiment also asked employees to judge the helpfulness of the answers, without first being told whether they came from the CEO or the CEO Bot. Employees generally favored the responses they perceived as coming from the human CEO over those they attributed to AI, suggesting a deep mistrust of algorithms.

To explore this phenomenon further, Choudhury and his team conducted a second study that aimed to control for those perceptions. Researchers asked a second group of participants to evaluate answers given by the CEOs of Hershey, General Motors, Nvidia, and Amazon during earnings conference calls against AI-generated responses to the same questions:

Hershey CEO: “We’ve continued to invest in capacity in brands and businesses across the portfolio that have growth and opportunity ahead….”

AI-generated response: “At Hershey, our capacity expansion plans are focused on several key areas to support our growth and meet increasing consumer demand. …”

In this phase, however, the labels on the answers were randomized. Choudhury and his team uncovered a seeming paradox that sheds light on the challenges ahead for AI acceptance: messages simply labeled as coming from AI were rated as less helpful than those that actually came from a chatbot.

“My prediction is that every single employee one day will have their own communication bot, just like today we all have email,” Choudhury says. “But the question is, how do we get this to work, so it’s credible and widely accepted?”

The significance, Choudhury says: “The real employees of the CEO, the folks who know the CEO well, cannot identify which answer came from the human and which came from the bot.”

Personal communication chatbots

The experiment also asked employees to judge the helpfulness of the answers, without first being told whether they came from the CEO or the CEO Bot. Employees generally favored the responses they perceived as coming from the human CEO over those they attributed to AI, suggesting a deep mistrust of algorithms.

To explore this phenomenon further, Choudhury and his team conducted a second study that aimed to control for those perceptions. Researchers asked a second group of participants to evaluate answers given by the CEOs of Hershey, General Motors, Nvidia, and Amazon during earnings conference calls against AI-generated responses to the same questions:

Hershey CEO: “We’ve continued to invest in capacity in brands and businesses across the portfolio that have growth and opportunity ahead….”

AI-generated response: “At Hershey, our capacity expansion plans are focused on several key areas to support our growth and meet increasing consumer demand. …”

In this phase, however, the labels on the answers were randomized. Choudhury and his team uncovered a seeming paradox that sheds light on the challenges ahead for AI acceptance: messages simply labeled as coming from AI were rated as less helpful than those that actually came from a chatbot.

“My prediction is that every single employee one day will have their own communication bot, just like today we all have email,” Choudhury says. “But the question is, how do we get this to work, so it’s credible and widely accepted?”

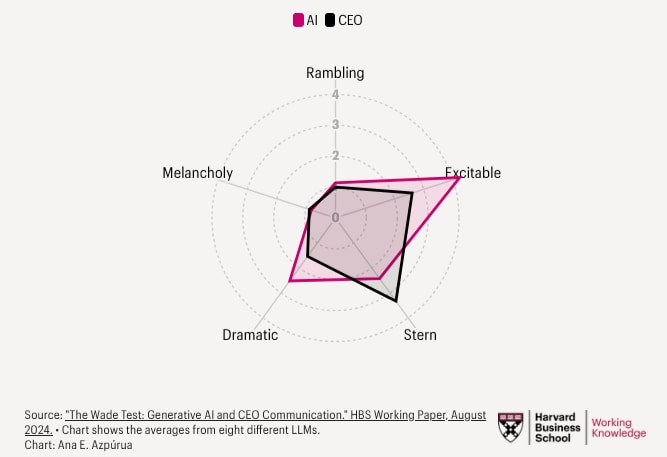

AI vs. CEO: communication styles ranked

On a scale of 1 to 10, employees viewed AI-generated answers as more dramatic and excitable, while those from the Chief Executive Officer were perceived as more stern.

“My prediction is that every single employee one day will have their own communication bot, just like today we all have email,” Choudhury says. “But the question is, how do we get this to work, so it’s credible and widely accepted?”