A bomb blast and an earth-shattering event some 100 kilometres away. But in a strange twist of fate, they altered Kalyan Jewellers’ fortunes forever.

It was back on a gloomy Valentine’s Day in 1998 that 12 bombs went off, one after the other over six hours in the southern city of Coimbatore, often referred to as the Manchester of Southern India, killing 58 people and injuring as many as 200. The blasts were a retaliation for the riots that took place in the city a year ago.

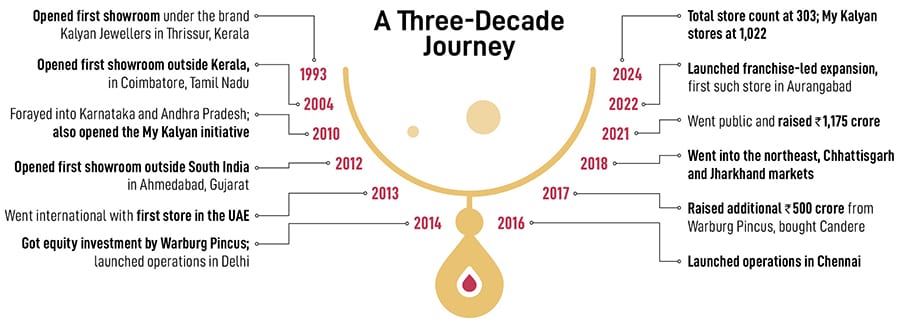

Sitting in his 4,000 square feet jewellery shop in the cultural capital of Kerala, Thrissur, little did the then-51-year-old TS Kalyanaraman think about the seismic impact it would have on his destiny. Until then, the now-₹72,000-crore jeweller (by market cap) had remained a single-store retailer of gold jewellery in the southern state of Kerala. Kalyan Jewellers had started operations five years ago, in 1993, in Thrissur, where Kalyanaraman had previously built a textile business.

“The blasts in Coimbatore meant that people from Palakkad soon stopped going there for their purchases,” Kalyanaraman tells Forbes India. “They kept inviting us to set up a store in Palakkad.”

Palakkad, a historic township, often referred to as the rice bowl of Kerala, was less than 50 kilometres from Coimbatore, with a significant populace from the region choosing to cross the interstate border to make their purchases. But the bomb blast significantly changed that trend, and the small gold shops in Palakkad were soon abuzz with business, as Malayalis in Palakkad preferred to make the purchases within the state.

Kerala and Malayalis count among the largest gold buyers in the country, with per capita spending on gold ornaments in rural parts as high as six times that of Goa, the second-highest spender on the yellow metal. In all, the state consumes between 200 and 225 tonnes of gold annually of India’s yearly demand of 747 tonnes.

Kerala and Malayalis count among the largest gold buyers in the country, with per capita spending on gold ornaments in rural parts as high as six times that of Goa, the second-highest spender on the yellow metal. In all, the state consumes between 200 and 225 tonnes of gold annually of India’s yearly demand of 747 tonnes.

“People stopped going to Coimbatore out of fear,” says Kalyanaraman, managing director of Kalyan Jewellers. “We realised that we could soon try our tested formula to build our business in Palakkad. And that was how our second store came up.”

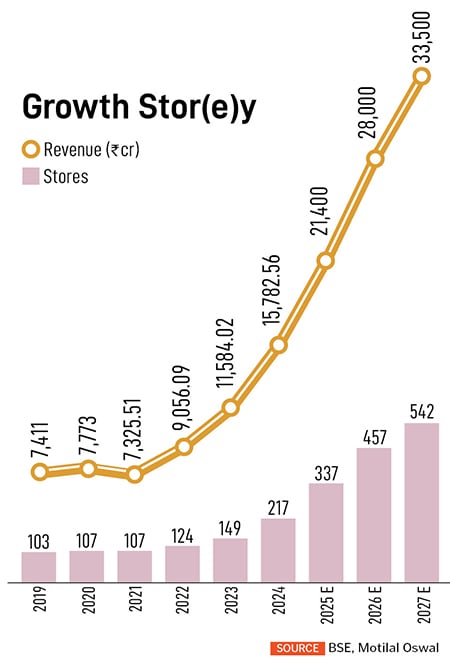

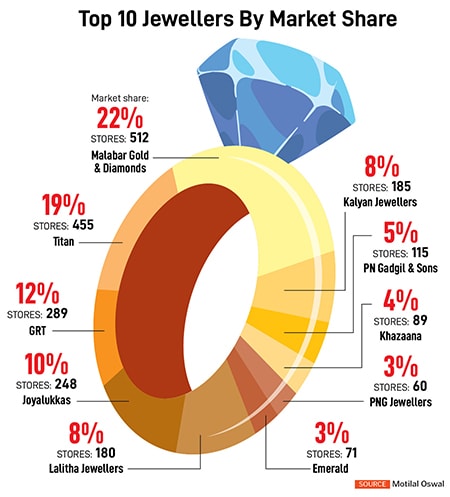

With that, the Kalyan growth story had just about started. Today, Kalyan Jewellers boasts as many as 303 stores across the world, 100 of which are through the franchise model. It is the second-largest gold jeweller in the country by market capitalisation. Many of its rivals—such as Joyalukkas and Malabar Gold—are yet to go public. Only Titan, with a market capitalisation of ₹2.82 lakh crore, remains ahead of Kalyan. Present across 23 Indian states, and five countries globally, it now employs over 12,000 people.

In the process, Kalyanaraman has also made a stunning return to the 2024 Forbes India Rich List, with a personal wealth of $5.38 billion. That also makes him the richest jeweller on the list, ahead of Joy Alukkas, who has a personal wealth of $3.3 billion.

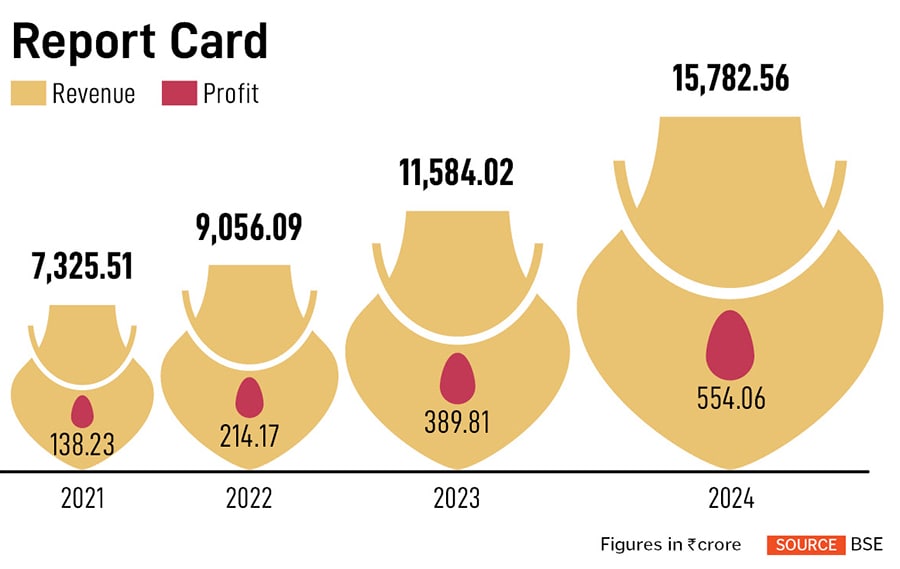

Last year, Kalyan Jewellers posted revenues of ₹15,782 crore, with net profits of ₹554.06 crore. Rival Titan, with 450 stores, posted revenues of ₹38,270 crore during that period, with net profits of ₹3,333 crore. Malabar Gold, the Kerala-headquartered gold jeweller, posted revenues of more than ₹50,000 crore last year. India’s jewellery business is largely fragmented, which means organised players only account for about 40 percent of the domestic market.

“For a long time, India did not have a clear number two pan-India jewellery player,” says Ankur Bisen, senior partner and head for consumer and retail practice at consultancy firm Technopak Advisors. “Kalyan has managed to fill that gap. Tanishq and Titan have the backing of the Tata Group, essentially a corporate. In the case of Kalyan, it is an instance of a regional and family-led player pushing through to become a national brand… and has also provided a template for others to follow.” Today, as much as 49 percent of Kalyan’s revenues come from outside the southern market.

Also read: Forbes India’s 100 Richest 2024: How Indian billionaires have continued their dream run

In this financial year, Kalyan has opened 60 shops across the world

In this financial year, Kalyan has opened 60 shops across the world

Rich Legacy

Even before he forayed into the world of jewellery, Kalyanaraman’s family had spent nearly a century in business, primarily in textiles.

His grandfather, TS Kalyararama Iyer, [In the Brahmin community in Kerala, parents often give the eldest child their grandfather’s name], set up a textile shop in Thrissur in the early part of the 19th century, something that his father, Sitharaman continued, alongside expanding the family business into tiles. By 1971, the Kalyan family partitioned their assets which had grown to include several textile shops. Kalyanaraman’s father received a shop, TS Kalyarama Iyer Textiles, near the district hospital in Thrissur.

In 1972, Kalyanaraman’s father set up a new textile shop for his son, soon after his graduation, as part of his plan to build a textile shop for each of his sons. “I used to mingle with all the customers closely,” says Kalyanaraman. “Everybody used to call me Swami Kutty then. Most of them would often ask me, why don’t you start a jewellery shop so that we can buy jewellery and textiles under one roof.”

By the early 1990s, India’s economy had undergone a sea change with the government unveiling the neo-economic policy that allowed for greater privatisation and liberalisation of the economy. The Indian rupee had begun to depreciate significantly after the government decided to devalue the currency, going from ₹17.5 against the US dollar in 1990 to ₹30 by 1993.

Kerala, which boasted a large immigrant population based in the Middle East, provided a massive opportunity since remittances now found greater value. Gold was one of the most sought-after investments in the country as alternative investments were yet to gain traction. In 1993, Kalyanaraman decided it was time to move away from textiles into the lucrative jewellery business.

“Both my sons were now ready to get into business and there was no space for the three of us to sit in one textile shop,” Kalyanaraman says. “I decided to diversify and everybody from my family had some suggestions—such as electronics or home appliances. That’s when I went back to my early days in textiles and thought about starting a jewellery business.”

With ₹25 lakh from his savings and another ₹50 lakh from borrowings, Kalyaranaman decided to foray into jewellery, setting up a 4,000 square feet jewellery shop in Thrissur. “Prior to starting the store, I had visited almost all the shops in Kerala and Chennai. And most of them were small, about 500 to 600 square feet.

Shopkeepers used to take orders for weddings and then they would supply the materials after a month or more,” Kalyanaraman says.

That meant an easy opportunity to keep readymade jewellery in their store for those looking for a faster purchase. “There were many who told me that we are going in the wrong direction in starting a big store like this,” Kalyanaraman recalls. “I thought if we have the blessings of God and the acceptance of the customers, that would be enough.” On April 8, 1993, the first Kalyan Jewellery store came up in Thrissur, and soon, with the wedding and festival season around the corner, it turned out to be an instant hit.

Kalyanaraman began by sourcing jewellery from many of his friends in the region, and from Mumbai, which helped bring in newer designs. The company also brought in some radical changes to the existing gold business, putting a barcode on all its jewellery to avoid theft, and ensuring BIS certification for its products, in its attempt to keep with the company’s guiding principle—trust.

Kalyan also put a price tag on each product, and details such as making and wastage charges along with the final price. “Trust… it is a simple word that sustains us,” Kalyanaraman says. “It means the world to us.” By the turn of the millennium, Kalyan had expanded its store count to three, with stores in Thrissur, Palakkad and Perinthalmanna in Kerala. By then, Kalyanaraman was clear that two stores would be managed separately by his two sons, while he kept one, something similar to what his family had done for many decades. Kalyanaraman’s father had set up five shops for his five sons.

Kalyan also put a price tag on each product, and details such as making and wastage charges along with the final price. “Trust… it is a simple word that sustains us,” Kalyanaraman says. “It means the world to us.” By the turn of the millennium, Kalyan had expanded its store count to three, with stores in Thrissur, Palakkad and Perinthalmanna in Kerala. By then, Kalyanaraman was clear that two stores would be managed separately by his two sons, while he kept one, something similar to what his family had done for many decades. Kalyanaraman’s father had set up five shops for his five sons.

The newfound success only stoked ambitions, and Kalyan Jewellers decided to foray outside Kerala. The company set up its first store in Coimbatore and followed it up by opening stores in Thiruvananthapuram, Kochi and Kollam. By 2010, the group’s total business grew to 35 showrooms spread across Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

“We are particular that we should not cheat any customers,” Kalyanaraman says. “Whatever they are spending is their hard-earned money. That is the principle followed by my grandfather and father. We still follow the same principle of trust and transparency.”

Today, the company claims to open a store almost every 10 to 15 days, mostly through a franchise model. “Jewellery is like food in our country,” adds Kalyanaraman. “It is hyperlocal. Right from the brand name to the inventory to the way of communicating, everything must be hyperlocal. Our brand, Kalyan, is a unique and relatable name across the country.”

Focus on Hyperlocal

While he attributes much of his success to God’s grace, Kalyanaraman knows that the brand’s success is also largely due to its focus on hyperlocal, which includes local campaigns, in addition to local inventory suited for that region. “It’s the same as a masala brand,” he explains. “There is no national brand. Similarly, in the gold business, it all depends on providing local taste.”

To do that, the brand brought on numerous regional brand ambassadors, who also embody trust for the local market. Kalyanaraman recounts the example of southern star Prabhu Ganeshan, the son of legendary actor Sivaji Ganeshan, who became the brand ambassador in Tamil Nadu early on and remains one to this day. Similarly, Shiva Rajkumar, the son of legendary actor Rajkumar of Karnataka, was brought in, while Telugu superstar Nagarjuna, son of renowned actor Nageshwara Rao Akkineni, was signed on.

The company also signed on Bollywood mega star Amitabh Bachchan for its pan-India presence, which means that the group now boasts some of the best-known faces in the country. “Who better than some of the most trusted actors to convey our story of trust?” Kalyanaraman asks. “We spent a good number of years to only educate customers on how to buy gold, on how they should not get cheated… we did a lot of campaigns around that.”

The company claims to be the first gold brand to bring on a male brand ambassador, southern superstar Mammooty. “What happened over time was that we became one of the most trusted jewellers. Today, that’s our intangible asset, after many years of growth.”

“Having numerous brand ambassadors across regions has helped Kalyan Jewellers become a household name in the country,” says N Chandramouli, CEO of market research firm TRA. “In the process, they have truly become a national brand and have been able to make inroads into markets such as rural Punjab, for instance. They have also been prudent in their approach as far as spending is concerned.”

Kalyan’s list of brand ambassadors today comprises the Bachchan family, Katrina Kaif, Rashmika Mandanna, Janhvi Kapoor, Kriti Sanon, Kalyani Priyadarshan, Nagarjuna Akkineni, Prabhu Ganeshan, Shiva Rajkumar, Pooja Sawant, Wamiqa Gabbi, Kinjal Rajpriya and Ritabhari Chakraborty.

Additionally, the company also set up what it called ‘My Kalyan’ stores, a small customer outreach and service centre across smaller towns, in its attempt to become a neighbourhood jeweller. These stores, which grew to account for almost 20 percent of the revenues by 2020, offered traditional and modern designs of diamond jewellery within the range of ₹5,000 to ₹15,000, making it easily available for those in rural regions.

Additionally, the company also set up what it called ‘My Kalyan’ stores, a small customer outreach and service centre across smaller towns, in its attempt to become a neighbourhood jeweller. These stores, which grew to account for almost 20 percent of the revenues by 2020, offered traditional and modern designs of diamond jewellery within the range of ₹5,000 to ₹15,000, making it easily available for those in rural regions.

In 2014, the company raised money from private equity firm Warburg Pincus at a time when its store count had grown to 50. By then, Kalyan Jewellers had become a prominent player in the southern market and was gunning for a national presence. But to grow into a national brand meant that the company either had to try the Titan formula, which would effectively restrict its product offering without any local designs, or try its tested formula of targeting customers with hyperlocal designs.

Choosing the latter would mean spending an enormous amount of money. That’s also why the family, which has been in business for more than a century, decided to look at private equity. Warburg Pincus invested ₹1,200 crore in Kalyan, valuing the company at $2 billion. It was the first instance of private equity investment into the jewellery sector. In 2017, Warburg Pincus invested another $77 million, by which time the company’s stores had grown to 106.

In 2017, the company also acquired online jewellery firm Candere as part of its plan to expand into the fast-growing online sector. Candere now operates as an omnichannel arm of Kalyan Jewellers. “They were among the earliest movers into the D2C segment by acquiring Candera,” adds Bisen. “That speaks volumes about the forward-looking nature of the promoters.”

Gunning for More

By 2021, Kalyan Jewellers went public, raising as much as ₹1,175 crore from the bourses, with its offer being subscribed 2.61 times. The following year, it decided to build on a franchise model, to scale up its growth, and launched its first model under the Franchise Owned Company Operated (FOCO) model in June 2022.

Under a FOCO model, the franchisee owns the store and is responsible for the investment in setting it up, while the company controls day-to-day operations, including staffing, management and inventory, which gives it control over the product and service. In return, it frees up the company’s balance sheet.

Under a FOCO model, the franchisee owns the store and is responsible for the investment in setting it up, while the company controls day-to-day operations, including staffing, management and inventory, which gives it control over the product and service. In return, it frees up the company’s balance sheet.

Today, the company has more than 100 stores under the franchise model. “Our expansion has completely taken shape through franchise partners,” adds Kalyanaraman. “Because we are freeing up the balance sheet, the capital sits with us, and we can reduce our loans.”

“The asset-light expansion will generate the necessary cash flows to repay its debt in India (around ₹600 crore) over the next two years,” brokerage firm Motilal Oswal said in a recent report. “The studded ratio of 28 percent in FY24 was best-in-class and reflected the company’s understanding of evolving consumer trends such as youth-led and non-traditional preferences.” Studded ratio means jewellery with studded stones compared to plain gold jewellery.

Now, with the franchise model reaping rich dividends and a brand recall value that’s become stronger, Kalyan Jewellers is gearing up for further growth across regions, including penetrating deep into the South in addition to its foray into the US market, close on the heels of its rivals, including Malabar Gold and Joyalukkas.

India’s organised jewellery business, which comprises the likes of Joyalukkas, Kalyan Jewellers, Titan, Malabar Gold and Senco, among others, contributes to less than 40 percent of India’s gold purchases.

The country is the world’s second-largest consumer of gold, and consumption stood at 747.5 tonnes in 2023, according to the World Gold Council (WGC). Demand for gold jewellery in 2023 stood at 562.3 tonnes compared with 2022, according to WGC. This year, the WGC expects gold consumption to rise to 900 tonnes, even as prices rise, signalling huge growth for retailers.

India’s jewellery retail sector was worth $80 billion (₹6.4 lakh crore) in FY24, according to estimates by brokerage firm Motilal Oswal. Of the total gold consumption in India, 66 percent was for jewellery, and the remaining for bars and coins. The sector is expected to grow to $145 billion by 2028, of which organised retail is expected to account for 43 percent.

“Competition is always there in this industry,” Kalyanaraman says. “We have never seen this industry without competition. We have always survived the competition, and we know how to tackle competition, how to be different from them.”

Now, with India’s jewellery business emerging into four broad categories, according to Kalyan, the company reckons that it has a stronghold in two of those segments and is gearing up to build on a third one. “Today, within the organised segment, there are four categories,” Kalyanaraman explains. “There are regional players who focus on regional markets, players like us who have hyperlocal products as well as national ones, then there are online and D2C-focussed brands such as Melorra, CaratLane, Bluestone, and the fourth category is luxury jewellery.” Except for being a regional player, Kalyan claims to be available in all the remaining categories.

The big growth in the coming years, Kalyan reckons, will come from the third category, which includes products priced between ₹15,000 and ₹25,000. Candere operates in that segment. “We see huge growth in the segment,” Kalyanaraman says. “Our focus now is to invest in geographical presence for Candere along with investment into technology, and hopefully, we should be able to build it like Kalyan.”

In this financial year, Kalyan has opened 60 shops across the world, which means Kalyanaraman and his two sons, who serve as executive directors, are gearing up for more, especially with the franchise model. It also helps that they have their tasks cut short, with a well-laid-out management structure comprising a CEO who looks after the day-to-day running and expansion activities. Vinod Rai, former Comptroller and Auditor General of India, is the chairman of Kalyan Jewellers.

“If you want to see what Kalyan has done to the jewellery segment, just look at all the jewellers who followed Kalyan in going public,” Bisen of Technopak says. “Everybody from Senco to PN Gadgil and Manoj Vaibhav have raised money from the public after Kalyan’s success.”

For Kalyanaraman, though, the mission remains simple and clear. To hold on to the family’s century-old goodwill and trust, something that his grandfather had inculcated in him.