Surender Saluja with son Chiranjeev (right), the managing director of Premier Energies

Surender Saluja with son Chiranjeev (right), the managing director of Premier Energies

Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti

Surender Saluja has one small regret—that he could never be an employee. It would have been nice, he says, to get the exposure of working in a company in the early years of his career. But as things turned out (for the good, of course), as soon as he graduated with an engineering degree in 1969, he became an entrepreneur. He started out small with a few ventures, but the idea that would make him a billionaire came to him in 1995, when he started building a business to generate power from the sun. His logic was simply that sunlight was freely available, sustainable and required no raw material.

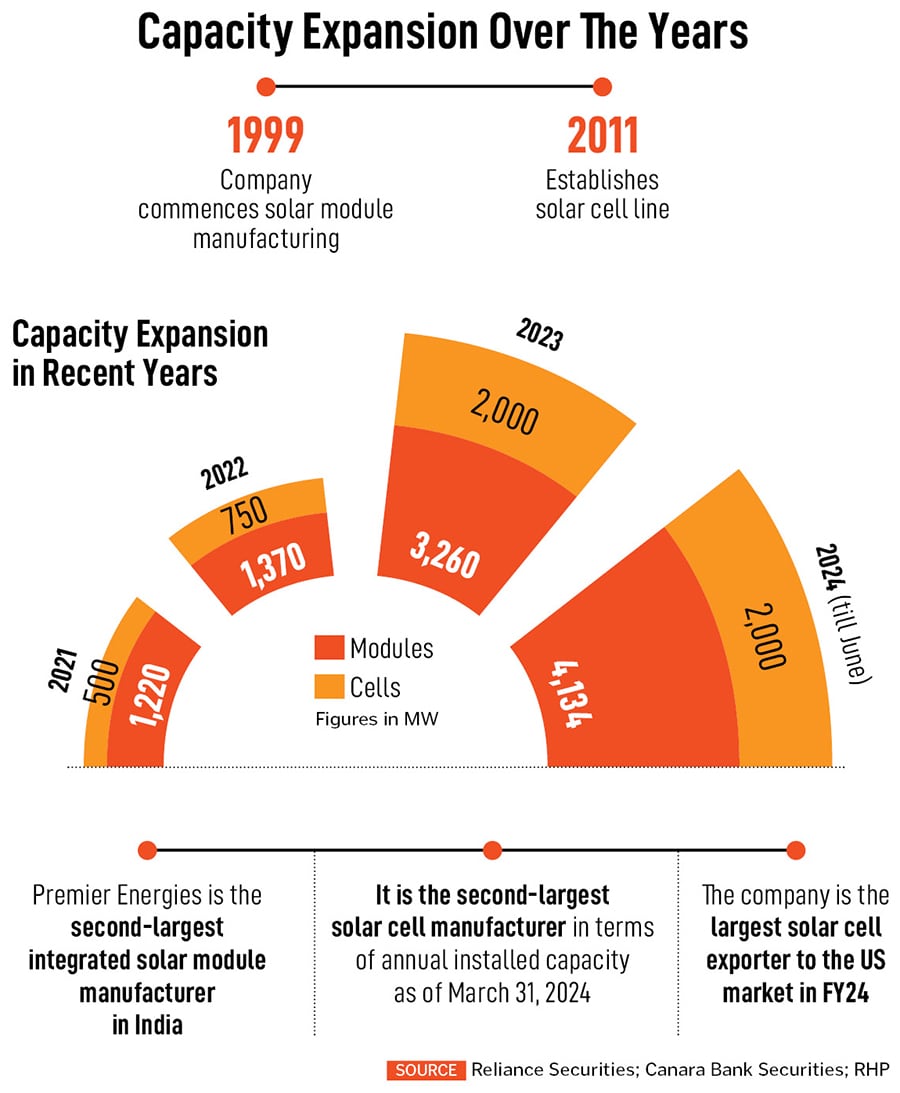

Saluja set up Premier Energies in Hyderabad in 1995, at a time when not many people knew about the potential of solar energy. He remembers how they would take a DC bulb and connect it to a solar plate using two wires to show how it could produce power. The company started with basic products like solar lanterns and streetlights, and executed projects that involved installing solar installations in remote villages that did not have access to electricity. In 1999, they commenced solar module manufacturing.

From thereon, the company went from one milestone to another, like establishing a solar cell line in 2011, and recently, expanding manufacturing capabilities to the US. They have five manufacturing facilities in Telangana. Their solar cell manufacturing capacity stands at 2 GW (gigawatt), while module manufacturing capacity is at 4.13 GW. They are the second-largest makers of integrated solar cells and modules in India after the Adani Group’s Mundra Solar Energy, and the largest solar cell exporters to the US market in FY24.

Being an early mover in a sunshine sector has been among the biggest strengths of Premier Energies, one that held it in good stead when Saluja and his son Chiranjeev, the managing director of the company, decided to take it public earlier this year.

Being an early mover in a sunshine sector has been among the biggest strengths of Premier Energies, one that held it in good stead when Saluja and his son Chiranjeev, the managing director of the company, decided to take it public earlier this year.

The company made a stellar debut on the stock markets on September 3. Its shares listed at ₹990, marking a 120 percent premium over the issue price. The company’s market capitalisation crossed ₹50,000 crore at the time of listing. This also earned Saluja a spot in the 2024 Forbes India 100 Rich List, where he debuted at Rank 85 with a net worth of $3.7 billion.

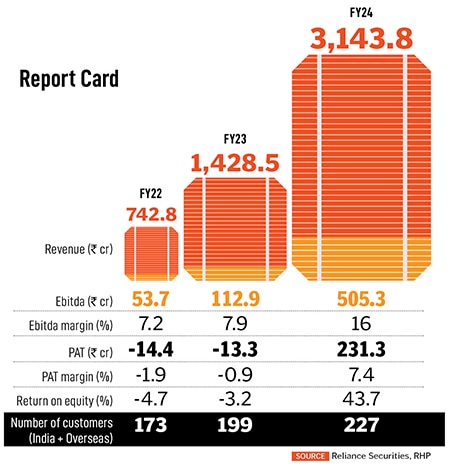

In its earnings for the September-ended quarter, the company showed revenue and profit growth, with improved Ebitda and PAT (profit after tax) margins. Total revenue stood at ₹1,553 crore, up from ₹701 crore in September 2023. Ebitda margins rose from 15.25 percent in September 2023 to 26.19 percent in September 2024. PAT, for the same period, increased from ₹52.85 crore to ₹206 crore.

The valuations for Premier Energy have been on the higher side since their blockbuster listing. The stock price has moved up, and investors will now be watching out for the company’s performance over the next few quarters, says Vikas Inder Jain, head-research, Reliance Securities. “Some earnings growth has to happen, and depending on how that materialises, there will be a price correction accordingly.”

Chiranjeev, 51, has charted out an aggressive capacity expansion strategy to further fuel revenue growth in the coming quarters. The funds raised through the IPO are to be used to this end. One ambitious plan is to set up a greenfield 4GW TOPCon solar cell and module line, for which 75 acres of land has been allocated by the Telangana State Industrial Infrastructure Corporation. TOPCon solar panels are more energy efficient than other conventional ones.

The project costs ₹3,200 crore, out of which around ₹1,000 crore primary raise was through the IPO and ₹2,200 crore delta is coming from the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA), says Chiranjeev. “With this project, our capacity will move from 2 GW to 7 GW solar cells, and from 4 GW to 8 GW modules.”

He tells Forbes India that their long track record aside, the reason Premier Energies is reaping rewards today is because of investing in expansion plans and staying ahead of the technology curve. A long-term strategy, therefore, is laying the ground to move up the solar photovoltaic value chain, on which China currently has over 80 percent dominance.

Also read: Piramal Enterprises fights challenging times

From Partition to Premier

Chiranjeev is a third-generation entrepreneur. The family hails from Mirpur, which is now part of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Saluja was barely a year old when the family moved to India during the Partition of 1947. They settled down in Ayodhya where his maternal grandparents lived.

About a year or so later, Saluja’s father, along with a friend, boarded a train to start a career afresh. He had no destination in mind, and could have disembarked anywhere, but he chose Secunderabad, the twin city of Hyderabad that the family now calls home. “They came with an open mind. They had no one waiting for them here, but they saw that it was a beautiful place, a Cantonment area, and decided to settle down,” says Saluja, 77.

His father started manufacturing peppermint under the License Raj and going shop-to-shop on a bicycle to sell it to small vendors and grocery shops. He did that business for seven to eight years. His father then started taking on government contracts to source and supply industrial materials.

Saluja—one of six siblings—graduated in mechanical engineering from Karnatak University, Dharwad, in 1969. During that time, the then-government of Andhra Pradesh launched a financing scheme to encourage young entrepreneurs. Saluja took a loan of ₹2 lakh, “one lakh for capex and one lakh for working capital”, to start Saluja Auto Industries. The company offered high tensile fasteners for automobiles, turbines etc. It shuttered after a few years.

Saluja—one of six siblings—graduated in mechanical engineering from Karnatak University, Dharwad, in 1969. During that time, the then-government of Andhra Pradesh launched a financing scheme to encourage young entrepreneurs. Saluja took a loan of ₹2 lakh, “one lakh for capex and one lakh for working capital”, to start Saluja Auto Industries. The company offered high tensile fasteners for automobiles, turbines etc. It shuttered after a few years.

In 1981, he got into the business of supplying pumps for rural drinking water supply, with a company called Premier Deep Well Hand Pumps. They exported to African countries, and were associated with Unicef (United Nations Children’s Fund), which had launched a programme for promoting access to rural drinking water. During this time, he learnt about the potential of solar power, and decided to start Premier Energies.

“It was a one-man show,” says Saluja, who started with selling solar lanterns, and graduated to building solar modules or panels manually. “We were smouldering each module, each cell, manually. It used to take time, which is why initially we decided to buy from Central Electronics Limited (CEL) in Ghaziabad,” he says, adding that Premier was among the very few private players in the module manufacturing space in India. “We bought the panels from CEL and just did the assembly,” he explains.

When Chiranjeev joined Premier Energies in 1997, much of their business was still off-grid solar lanterns and lighting, and revenues were less than a crore per year. “I started my career on the machine, learnt how to make solar panels on a laminator,” he says. Premier Energies started manufacturing solar modules in 1999. In hindsight, it was among their first steps towards backward integration up the solar manufacturing value chain.

At the time, making solar panels was expensive. There were no volumes, and raw materials too were not cheap. Saluja remembers how the first panel that they manufactured sold at ₹200 per watt. Today, they are selling for ₹14-16 per watt. “Everything was coming from China, even at that time,” he says.

“China+1”

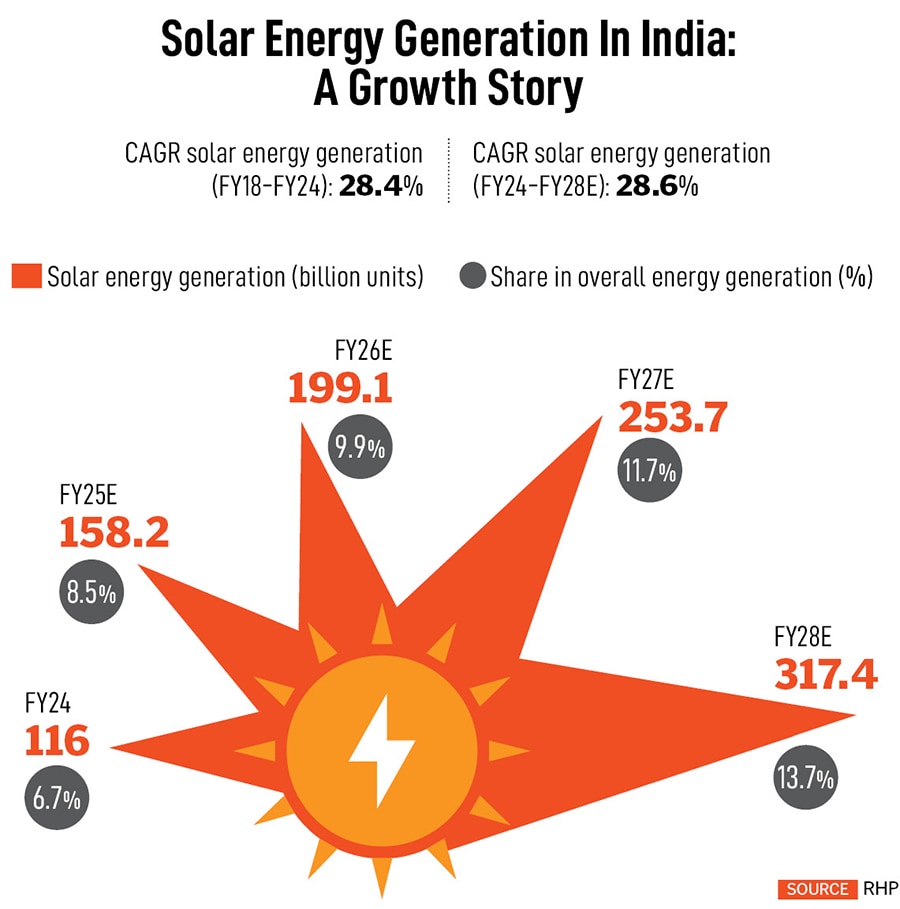

The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that the sun could be the world’s largest source of electricity by 2050, ahead of fossil fuels, wind, hydro and nuclear, and could prevent the emission of more than six billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2050. In India, the solar energy generation is expected to have a compound annual growth rate of 28.6 percent, increasing from 116 billion units in 2024 to 317.4 billion units in 2028.

The solar photovoltaic value chain goes from making polysilicon to ingots to wafers to cell and then the finished modules/panels. For many years, Indian manufacturers had been focusing on the downstream part of this value chain, which includes importing solar cells and assembling them into modules or panels.

The opportunities to leverage the power of the sun have opened up due to the rapid cost decrease of solar photovoltaic (PV) modules and systems, but the challenge is that it remains a capital-intensive business, with large upfront expenditures, while returns could take time to materialise. For example, Chiranjeev says that module manufacturing can cost around ₹150 crore per GW, solar calls around ₹600 crore per GW, ingot and wafer around ₹400 crore per GW, and polysilicon around ₹15,000 crore for a metric tonne per annum.

The current push by the Indian government, which ties into the criticality of solar in India’s targets of 500 GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 and net-zero by 2070, is to encourage manufacturers to go deeper into the value chain. This will reduce dependency on China for imports and lower the cost of solar panel production in India in the long run.

“Today, 80 percent polysilicon is made in China, and nearly 98 percent of ingot wafer for the solar panels is made in China. That’s why the government wants to spur local manufacturing, starting with ingot wafers,” says Chiranjeev. Around 60 percent of India’s 500 GW target is going to come from solar, which means deployment of at least 50-60 GW year-on-year, he adds.

“Demand is going to almost double in the coming years. Capacity is also coming up, but a lot of work needs to be done for backward integration,” he adds. “There are only two large manufacturing bases in the world focussed on solar. One is China and the other is India. So it’s a great opportunity for India to be China+1.”

So apart from the 4 GW TOPCon greenfield project, Premier Energies is also setting up a 2 GW silicon wafer manufacturing facility with a Taiwanese partner, with an investment of ₹200 crore. “We also have plans to get into ingot manufacturing, which is the raw material need for the silicon wafer. That will require a capital investment of about ₹550 crore for 2 GW, which is also in the works,” says Chiranjeev. “We will stop there as far as backward integration in the value chain is concerned. Beyond that is polysilicon manufacturing, for which we might look at larger players in India.”

The company is also getting into aluminium manufacturing, and is looking to set up an aluminium frame factory with an annual capacity of 36,000 metric tonnes for captive consumption.

Premier Energies factory in Hyderabad

Premier Energies factory in Hyderabad

SWOT Analysis

Jain of Reliance Securities says the competition in the solar energy space is heating up, with competitive companies like Waaree Energies having successful IPOs in recent times. Only time will tell if the share prices will sustain, he says, given that they will also be influenced by factors like higher supply and limited demand.

In their IPO note for Premier Energies on August 26, Sankita V of Canara Bank Securities states that “expansion of their annual installed capacity, despite existing underutilisation may adversely affect their business, financial condition, and results of operations if there is insufficient demand for their products”.

While India has set high renewable energy targets, on-ground challenges for power generation and transmission, like land acquisition, often lead to delays in project execution. This has an impact on companies like Premier Energies, whose clients include power generation companies. The Canara Bank Securities note says the time lag between purchasing raw materials and realising sales from finished products and services is significant, which necessitates maintaining adequate raw material and sufficient capital for operations until they recover project costs.

Chiranjeev says the company has a signed order book of ₹6,200 crore as of the quarter-ended September, and “lines are working at over 90 percent utilisation factor”. Geographical expansion plans are also underway, with the company looking at facilities in Andhra Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, apart from setting up a 2 GW manufacturing line in the US through a joint venture with module manufacturer Heliene.

As per the red herring prospectus the company has filed with regulator, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, around 43 percent of their revenues for FY24 (some ₹1,360 crore) came from the top five customers, and that “the loss of one or more of such key customers for any reason… could have an adverse effect on our business, results of operations and financial condition”.

Chiranjeev agrees that maintaining relationships is crucial, and that their 29-year-old track record helps them maintain strong relationships and secure repeat orders. In the past three fiscals, the number of domestic and overseas customers has increased from 173 in FY22 to 227 in FY24. These include independent power producers, original equipment manufacturers, and off-grid operators. Some of the companies are Continuum Green Energy, BluePine Energy, Sembcorp, National Thermal Power Corporation, and Asantys Solar Systems, Panasonic and Tata Power Solar.

He also has an eye out for technological upgradations, which he feels is essential to make solar panels that are more efficient and bring the costs down. For example, he talks about the tandem cell technology, in which a perovskite layer on top of the TOPCon cell will take the efficiency from 25 percent to 30 percent. “We are looking at perovskite coming into the market in four to five years. As this efficiency goes up, costs will come down, you will require lesser land space, lesser balance of system to set up a large power plant,” he says.

No matter which way the market turns, Chiranjeev is confident that the company is here to stay. He says when he used to offer customers a warranty of 25 years on their solar panels, many wondered whether the company would survive for so long. “We turn 30 next year, and are among the few companies in this space that have survived the warranty period,” he says.