But Zomato CEO Deepinder Goyal’s faith and conviction shone through. “Trust me,” he had told the board as he explained how he planned to turnaround the business.

“I was apprehensive as nobody had earlier made a profit in this space,” Sanjeev Bikhchandani, co-founder, Info Edge, and the largest shareholder of Zomato, recalled in an interview on Forbes India Pathbreakers earlier this year. “It’s truly remarkable what’s happened with Blinkit.”

Goyal’s eyes light up as he shares that Blinkit is bigger than Zomato in some cities. “It’s growing 3-4 times faster and it is a matter of some months before it becomes bigger than Zomato,” he said in the interview in March. “Honestly, now Zomato’s 30-minute delivery feels slow.”

So, what changed in two years?

“There are several reasons for the explosive growth of quick commerce, but if we were to point to one unique value proposition quick commerce offers, the space it has claimed for itself, it would be effortless ultra-convenience,” says market research firm NIQ in a note published in September.

Goyal believes that quick commerce is a better model than ecommerce, and, at a certain throughput, it is actually cheaper to run as well if consumers increase the frequency of orders. “If you can get your headphones in matter of 7-8 minutes, why would you wait for a day on Amazon,” Goyal asks. “And Blinkit offers almost the same price, or it’s sometimes even cheaper than Amazon.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=/URlG03jaPQk

A recent study by Meta shows that 91 percent of Indian online consumers are aware about quick commerce and more than half of them have used it for convenience and efficiency, primarily for food, grocery, and personal care items. NIQ claims that quick commerce is the primary shopping platform for 31 percent of urban Indians. Besides, quick commerce is gradually finding acceptance in Tier 2 and Tier 3 markets also.

In response to evolving consumer preferences, FMCG companies are strategically building presence on quick commerce platforms to gain an edge over market peers. “If we want to win in this category, we have to be very agile,” says Masaba Gupta, founder, Lovechild, a D2C beauty brand. “We’re listing our lipsticks on Blinkit and Zepto.”

Cosmetics to masalas to flowers to iPhones—quick commerce has reimagined the buying habits of a large segment of consumers who do not want to plan purchases in advance and want orders delivered almost instantly. There’s also a sharp uptick in impulse sales due to the availability of a wide catalogue of products across different categories.

Also read: How open networks can help companies move from ‘Quick Commerce’ to ‘Quick Commerce Plus’

Also read: How open networks can help companies move from ‘Quick Commerce’ to ‘Quick Commerce Plus’

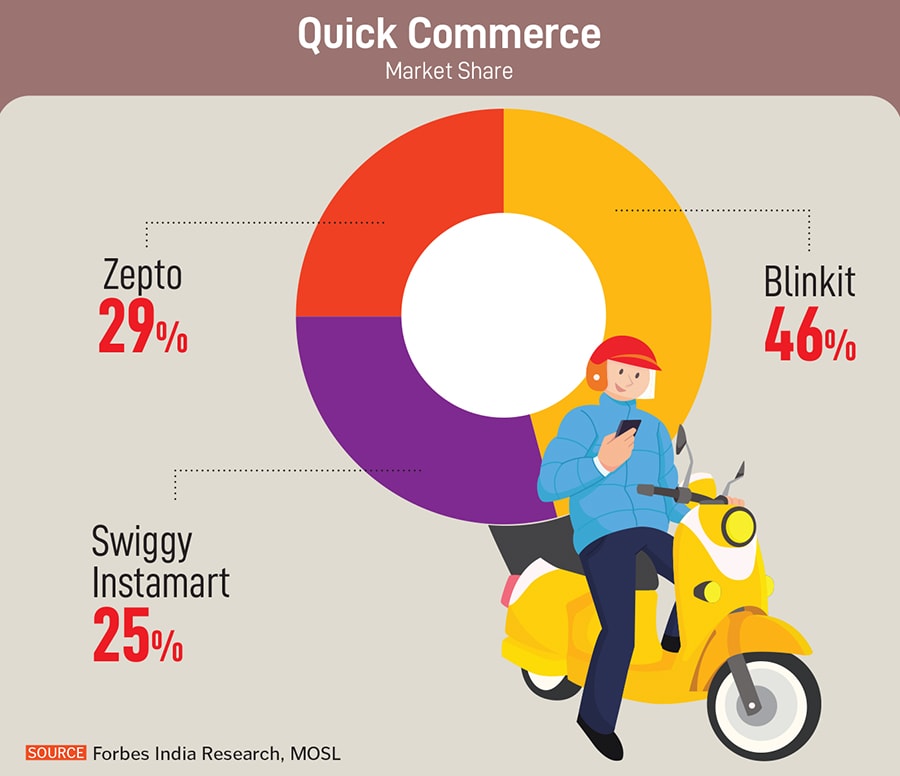

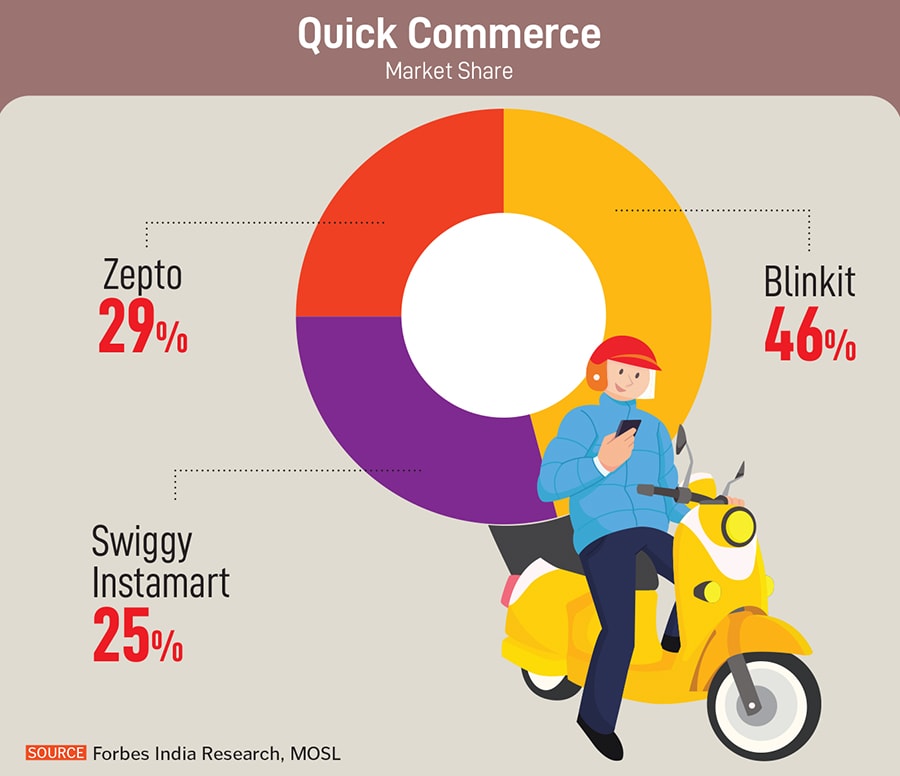

In fact, JM Financial estimates that the quick commerce market could be as big as $45 billion. The gross merchandise value (GMV) of leading quick commerce companies (Zomato-owned Blinkit, Swiggy’s Instamart and Zepto) have grown from under $1 billion in FY20 to over $3 billion in FY24, according to Redseer.

The rapid growth of the quick commerce sector has attracted many new players to enter the fray and capture a slice of the market pie: Beauty and fashion etailers such as Nykaa and Myntra have jumped onto the bandwagon too; ecommerce pioneer Flipkart has launched quick commerce services in select cities; Amazon is reportedly preparing to make a splash with quick commerce services next year; Bigbasket and Jio Mart are also evaluating opportunities.

In a pre-IPO conference, Swiggy co-founder and CEO Sriharsha Majety highlighted the growth potential of Instamart. “I think it is a generational opportunity,” he said. “We are really in the first few minutes of the game here in quick commerce.”

Even as incumbents and new entrants build a war chest and create business moats to emerge as the leaders in the increasingly crowded sector, a potential intervention by the government to protect offline groceries, or kirana stores, can lead to regulatory headwinds and derail growth plans. India has around 13 million kiranas that generate annual sales to the tune of $800 billion.

Also read: Where is 10-minute grocery delivery headed?

As per a JP Morgan survey, comprising 50 kiranas in suburban Mumbai, 60 percent respondents reported a decline in sales volume and most of them attributed it to quick commerce players. Nearly 62 percent of the respondents alleged that distributors and brands were giving quick commerce companies higher discounts and wanted the government to intervene and create a level playing field.

The new year could see more startups trying to solve this problem by bridging the digital gap for offline grocery owners who want to adapt and use technology to catalogue products for online ordering.

Quick commerce has reimagined the buying habits of a large segment of consumers who want orders delivered almost instantly

Quick commerce has reimagined the buying habits of a large segment of consumers who want orders delivered almost instantly

Also read:

Also read: