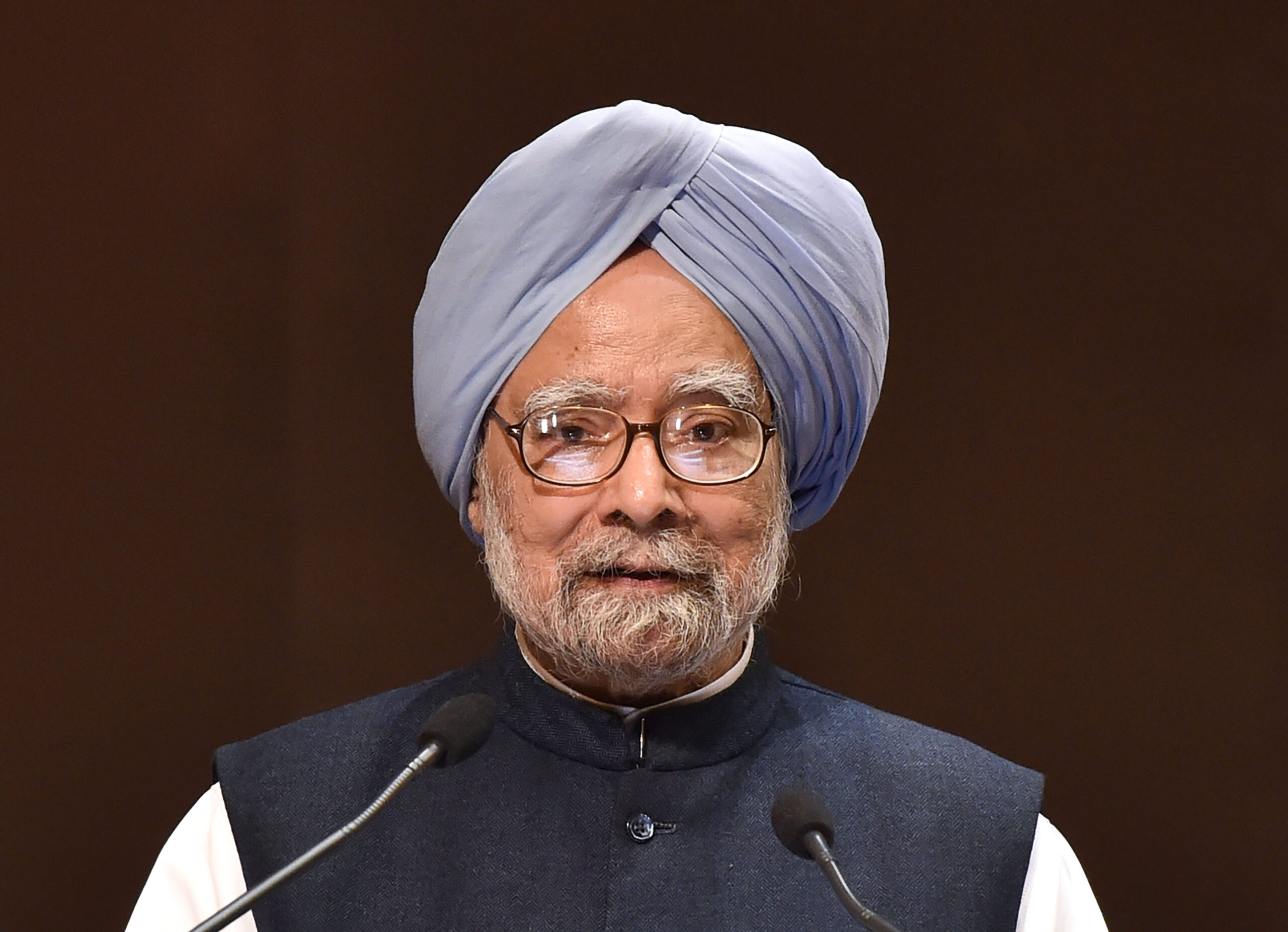

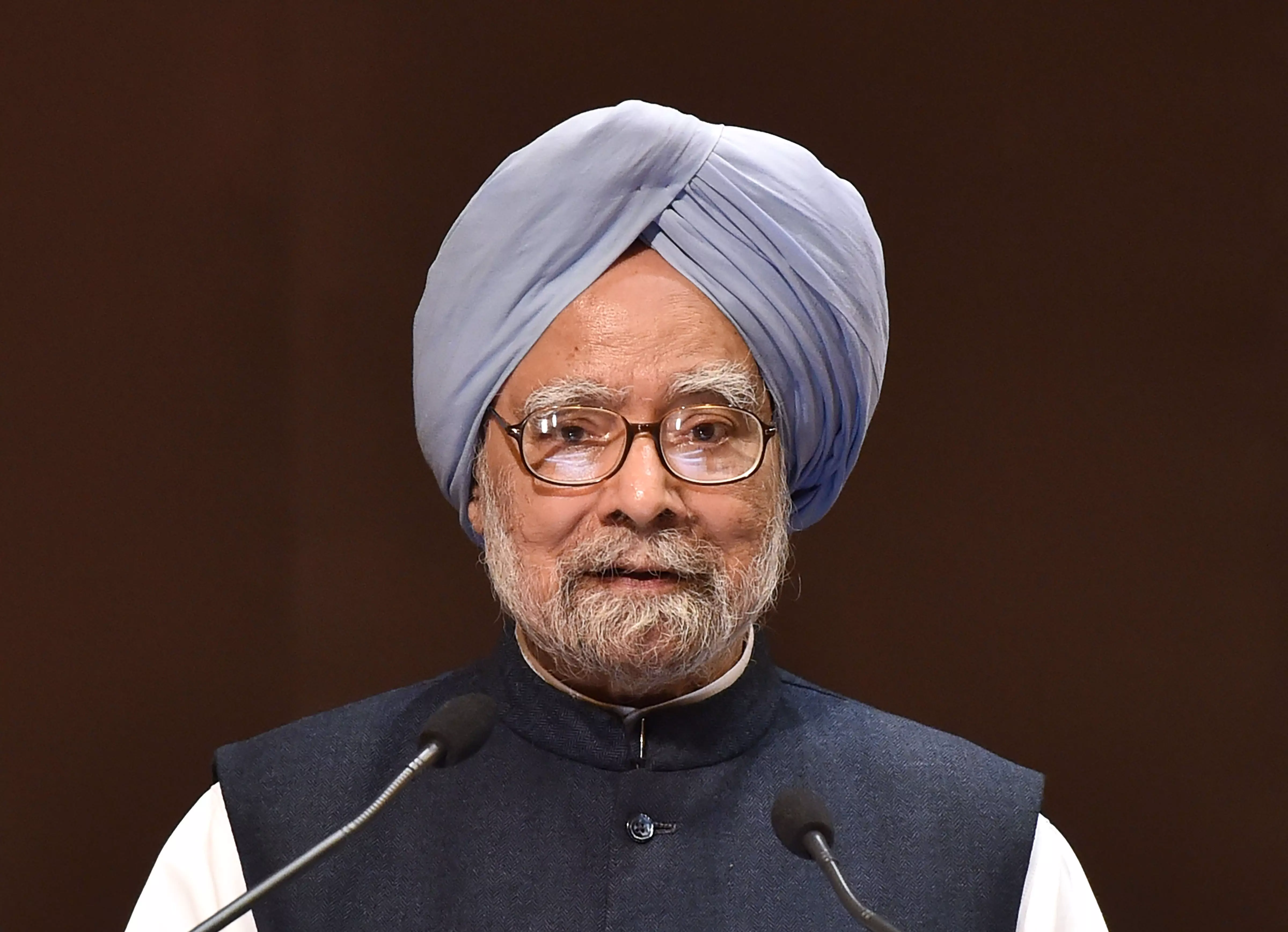

It is trite to say Dr Manmohan Singh was an institution. He was a colossus who strode the economic and governance firmament like an intellectual giant in a landscape populated by pygmies.

Born at Gah, now in Pakistan, he came across the Radcliffe Line to India as a refugee, like millions of others who lost their homes and hearth in the holocaust called Partition.

With sheer hard work and perseverance, he built a life as a distinguished professor, an economist of repute, finance minister and finally Prime Minister of India for a decade.

In his long and successful career, he held a diverse array of posts in academia and government. He was always polite to a fault, humble, self-effacing, the epitome of gravitas who carried success lightly on his shoulders.

As chief economic adviser, Reserve Bank governor, finance secretary and Planning Commission deputy chairman, among several high-level positions, he got an unique understanding of India’s economic and governance challenges.

As finance minister from 1991 to 1996 he leveraged this understanding to preside over the most fundamental reset of India’s economic trajectory when he dismantled the licence quota permit raj and unshackled the creative animal spirits of India’s economic entrepreneurs. This reset of India’s economic trajectory took place as the post-WWII world order collapsed and political scientists were predicting the “end of history”.

He created a new world for millions of young people who came of working age in the post-globalisation and liberalisation period. It is unfortunate India’s political lexicon and language never mirrored this economic reset and is populist to this day.

As Leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha from 1998 to 2004, he brought a quiet dignity and sobriety to that august office as political polarisation had already made parliamentary proceedings extremely toxic, to put it mildly.

As Prime Minister, he risked his government’s future to break the nuclear apartheid that had plagued India since the first nuclear test in May 1974 “when the Buddha smiled” in the Pokhran desert of Rajasthan.

After becoming Prime Minister in 2004, Dr Singh built upon the Jaswant Singh-Strobe Talbott dialogue in the aftermath of India’s second nuclear in May 1998, that led to a second reset in India-US ties by signing a “New Framework for India-US Defence Relations” on June 28, 2005, marking the full-scale start of defence cooperation between India and the US. Twenty days later, on July 18, 2005, the US and India announced the launch of the civil nuclear cooperation initiative. Under this, India agreed to commit all its civilian nuclear facilities to IAEA safeguards.

In 2004, the Congress had only 145 seats in the Lok Sabha. It was dependent on the critical outside support of the CPI(M), CPI and other Left parties who had 55 seats. Historically, the Left always had an anti-imperialist and anti-US worldview.

In June 2008, Dr Singh threw down the gauntlet and said India would go ahead with the US civil nuclear deal. Ironically, the BJP, which was the author of the reset with the US after the 1998 nuclear tests, and signed the “Next Steps in Strategic Partnership” in 2003, brought a no-confidence motion against Dr Manmohan Singh’s UPA government in July 2008.

Dr Singh in turn tabled a vote of confidence. Among stormy scenes in the Lok Sabha, with the BJP (Opposition) displaying wads of currency notes in the House, bringing proceedings to a new nadir, the government carried the day and won the vote, paving the way for the India-US nuclear deal to become reality, that was succeeded by the historical waiver by the Nuclear Suppliers Group, possibly the first ever for any non-signatory of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

In the general election of May 2009, the Congress swept every city in India from Thiruvananthapuram to Jammu — a fact attributed to the esoteric effects of the US nuclear deal which almost had a magical effect on the Indian middle classes, who probably never fully understood or appreciated its clauses and nuances.

Dr Singh’s second term was also marked by major reforms like permitting Foreign Direct Investment in Multi-Brand Retail. His foreign policy was characterised by a friendly relationship with neighbours, including a robust back-channel dialogue with Pakistan that produced a four-point formula, better known as the Manmohan-Musharraf Agreement. If implemented, it may have changed the dynamics of South Asia. But the 2007 Lal Masjid siege and the lawyers’ strike destroyed Gen. Musharraf’s political capital, and thus became a missed opportunity for not only India and Pakistan, but the region as a whole.

During Dr Manmohan Singh’s second term as PM from 2009 to 2014, the UPA-2 government was at the receiving end of the most torrid, toxic and corrosive onslaught by the media, which ironically got boundless opportunities after Dr Singh’s unshackling of the Indian economy. But Manmohan Singh never lost his calm or equanimity.

As his I&B minister and government spokesperson, I had to do the heavy lifting of putting the government’s point of view in the public space on a daily basis in 2012-2014. One day, flying to Ludhiana, my erstwhile parliamentary constituency, for the golden jubilee celebrations of the Punjab Agriculture University in December 2012, I asked him a conceptual question: What should be our approach to the media? Without batting an eyelid, he responded: “It should be an essay in persuasion and not an essay in coercion”. I pushed back, saying a biased and agenda-driven paradigm can’t be influenced by persuasion as they are just puppets on a string, whose masters are elsewhere.

He was unconvinced and said: Put yourself in the shoes of the Opposition and try and imagine what would think if the entire media turns into a government mouthpiece.

A true democrat, his prophetic words came true in the decade that followed his premiership.

On January 3, I anchored his mega press conference at the new National Media Centre. It was a cold wintry morning. Dr Singh gave an excellent summation of his ten years as PM. Replying to a question, he said philosophically: “History will judge me kindly”.

The press, however, concentrated on his announcement that he would retire in May 2014 after completing his second term. One newspaper even ran a photograph of an exit sign over a door, with Dr Singh walking towards it. It was an eloquent testimony to the ignominy he was put through — primarily because he was a decent person.

On December 26, 2024, as he breathed his last, all that we need to say is that a gentleman is with us no more. Adieu, Sir: another world awaits.