Aditya Pittie, Managing Director, Pittie Group. Image: Mexy Xavier

Aditya Pittie, Managing Director, Pittie Group. Image: Mexy Xavier

Both sides were evenly matched. Both factions could flex their bulging muscles to drag the other into submission. Both the camps swore by their unshakeable beliefs. For Aditya Pittie, though, the neck-and-neck fight between his heart and mind made the tug-of-war emotionally exacting. In 2005, the grad from King’s College London joined the family business of real estate in Mumbai. Back then, Pittie was just 21. Over the next few years, the dutiful son polished the family silver, aced the nuances of running a media empire with spiritual channels Sanskar TV, Satsang TV and Shubh TV, and by 2014, the young next gen proved his mettle. A glowing report card sedated his mind, nixed all wavering thoughts about businesses outside the boundaries of the family, and reassured the merits of building on the legacy. There was no need to deviate.

Pittie’s heart, though, pined for an independent way of life. A deeper introspection nudged him towards an uncomfortable question: What is better? A cosy life or building something from scratch? While the former would have certainly ensured the financial snugness that comes with family businesses, the latter would have brought in its wake one definite thing: Loads of uncertainty. Though Pittie had scaled the family business, he was still not the founder. The young entrepreneur had an irresistible itch to undertake the ‘zero to one’ journey.

What also stoked his impulse was a compelling need to go through the rites of passage: Entrepreneur to founder. “Unless you have built a business, no matter how hard you work, you will always be perceived as a surrogate,” Pittie said to himself, mustered courage, and initiated a heart-to-heart talk with the patriarch who sensed the uneasiness of his son. “For me, it was about moral and not legal ownership,” underlines Pittie, who took the first bold step in his solo journey by launching Baba Ramdev-backed Patanjali’s products across modern trade (MT) formats such as supermarkets in 2014.

Pittie was convinced about the upside of the bet. “It was a ‘made in heaven’ opportunity,” he recounts, alluding to the move of marrying rustic ayurveda with sleeky supermarkets. There was a downside as well. For the kirana-driven mass brand, supermarkets meant a trimmed appeal as only a niche section of consumers preferred shopping in the air-conditioned alleys. Undeterred, Pittie took the plunge, and the gambit paid off handsomely. Patanjali started clocking big numbers at Reliance Retail, Spencer’s and DMart. Pittie was credited for the blockbuster performance of Patanjali across modern trade.

Pittie was convinced about the upside of the bet. “It was a ‘made in heaven’ opportunity,” he recounts, alluding to the move of marrying rustic ayurveda with sleeky supermarkets. There was a downside as well. For the kirana-driven mass brand, supermarkets meant a trimmed appeal as only a niche section of consumers preferred shopping in the air-conditioned alleys. Undeterred, Pittie took the plunge, and the gambit paid off handsomely. Patanjali started clocking big numbers at Reliance Retail, Spencer’s and DMart. Pittie was credited for the blockbuster performance of Patanjali across modern trade.

Though Pittie reaped success, a few years later he found himself in an eerily similar predicament. He cracked the distribution of Patanjali but was yet to build something from scratch. The products flying off the shelves were not his brands. A weird sense of emptiness haunted him, and the founder found himself torn apart by a familiar tug of war. This time, though, the stakes were high because of the distinctive product and marketing playbook that he was toying with.

There were two pointed questions. First, can consumer brands be built out of commodities? There were precedents. Take, for instance, salt. Tata built a formidable brand out of this commodity. There were other examples in cement, edible oil and spices. So, there was enough headroom for more brands in FMCG. Second, can brands be built and sold only in supermarkets? The critics and naysayers were quick to brand the ‘supermarkets-only’ gambit as bravado. The shoppers, they argued, throng to supermarkets to buy the brands of their choice at an irresistible deal. Pittie, though, had spotted something that the others couldn’t. In every city—even across Mumbai, Delhi and Bengaluru—some pockets are ‘Bharats’ and some are Indias. “Both coexist. But Bharat consumers are much bigger in numbers than their counterparts and they are value-for-money buyers,” he reckons.

Also read: Aspiration for premium brands driving ecommerce in small towns: Report

Armed with his theory, Pittie rolled out a range of daily puja-need brands under ShubhKart. But why wellness brands? Pittie dishes out three reasons. First, targeting large commoditised segments with less brand play and negligible pull made immense sense. Wellness (puja) happened to be one such segment. Second, the rich experience of running a plethora of spiritual TV channels provided deep insights into the behaviour and needs of consumers. Third, puja ticked all the boxes a founder yearns for: Massive TAM (total addressable market), sticky buyers, repeat users, and ample upselling opportunities.

With a prayer on his lips, Pittie started with Nirmal, an incense stick and dhoop brand. Soon, he rolled out a battery of other sub-brands under ShubhKart such as Darshana (brand for puja powders, oil and ghee), Nitya (brand for brass, steel, copper, and silver products such as bells, diya, and plates), Tejas (a wicks and candle brand), Surabhi (a camphor brand), and Gaugaurav, a brand for puja items made from cow dung, ghee and natural herbs. The pilot at five Reliance Retail stores across Mumbai was a huge success. Emboldened, the founder added more SKUs (stock-keeping units) and bloated the product count to over 350.

Then came the light bulb aka diya moment. The buyers were not loading their carts with all the items. This meant a quick rationalisation of SKUs, which was trimmed to 150. There was another realisation. The supermarket game could be aced only in three ways. And it was not one of the three but ticking all the three boxes. First, Pittie needed to build scale. Supermarkets are all about volumes. Second, the products have to be the cheapest in the segment and better than the rivals in terms of quality. A tough ask but it was possible only if one had manufacturing capabilities. So far, Pittie has been sourcing from the Bhuleshwar market in Mumbai. He needed to dump the strategy.

Also read: StarAgri: Aiming for the stars

Third, Pittie needed to reverse engineer. “One must listen to the consumers, and my consumers were supermarkets,” he underlines. Supermarkets understood what the shoppers were looking for, knew what was missing in a product and an assortment, and were aware brands had a ‘Big Brother’ attitude in listening to the feedback from stores. Pittie partnered with modern trade, embraced their inputs, and rolled out products with high chances of flying off the shelves. He also did something interesting by planting a point-of-sale person at the stores. “I had to grab the attention of shoppers inside the store,” he says. The first-time consumers, he adds, don’t come to supermarkets with the notion that they need to buy a particular brand. They want to grab the best value-for-money deals. This buyer’s insight simplified Pittie’s life. “You just need to make them try your products,” he says. If the product, he underlines, is best among the pack in terms of price and quality, it becomes a brand. The next time, a shopper will look for Nirmal, Tejas, or ChakaaChak (see box).

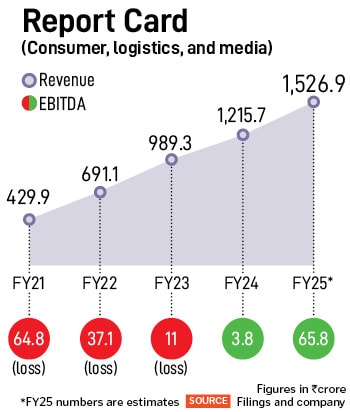

The ‘commodity-to-brand’ strategy seems to be working. Look at the numbers. In FY19, Shubhkart clocked sales of Rs10 crore. Five years later, it posted Rs118 crore in revenue in FY24. The brand is now clocking a run rate of Rs200 crore. ChakaaChak, a cleaning brand for home and homecare products, has grown from Rs4 crore in FY21 to Rs18 crore in FY24, and is all set to touch the Rs40-crore mark in March 2025. Pittie started Chakaachak with jhadu (broom), and then added dust pans, bucket mops and wipers. “Non-dust or plastic broom has become our bestseller,” he claims. “We built a brand out of jhadu,” he smiles, adding that the consumer division of Pittie Group has grown over five times from Rs24.7 crore in FY21 to Rs141.5 crore in FY24. “We are on track to touch the Rs300-crore mark by FY25,” he claims. What started with puja products under the wellness category now has three more revenue engines in homecare, personal care and food divisions (see box).

Industry experts are impressed with Pittie’s chakaachak (dazzling) success. “He started by identifying categories shunned by large companies and ignored by modern trade retailers due to its complicated nature,” reckons Damodar Mall, chief executive officer (grocery) at Reliance Retail. “That was a smart way to operate in a relatively safer place,” he adds. What helped him crack modern retail was his experience handling Patanjali’s products at supermarkets. “He managed the modern trade distribution for Patanjali during its startup days, heydays, and post-heydays,” contends Mall. In the process, Pittie learnt two things: How to create a supply chain backbone, and the nuances of modern trade. Usually, brands build for kiranas and then adapt for modern trade. “Pittie did the opposite. He made products that were designed for self-service stores,” he says, adding that Pittie’s brands were designed to be non-advertising brands. From modern trade, Pittie took his brands to ecommerce and now quick commerce. The beauty of his business model, Mall underlines, is that the modern trade doesn’t see him as a rival but a partner.

Interestingly, Pittie is not the first to build brands out of the crucible of supermarkets and modern trade. “The first to do so was Ajay Gupta who rolled out Ching’s Secret way back in 1995,” says Mall. Gupta didn’t have the financial clout to take the general-trade (GT) route. So, he bypassed kiranas, entered modern trade and made an impact. “He knew that success across supermarkets would make Ching’s a national brand,” says Mall, adding that most of the consumption categories in India are unbranded. So, there is a scope to churn out more brands. The biggest advantage for Pittie, he reckons, lies in going deep in the value space. “He is not building premium brands. As long as he plays the value game well, he will grow at a fast clip,” says Mall.

Also read: Adapt, diversify and grow: How the Kacham family business survived six generations

The challenge, though, for Pittie emanates from his business model itself. “Can somebody replicate the model and disrupt the disruptor?” asks Ashita Aggarwal, professor of marketing at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. If price is the biggest differentiator that pulls a consumer for the first time, then the same trick can be played by an aggressive competitor as well. People don’t throng to Zudio, the value brand from Tatas, only for low prices. “Has Pittie built the same playbook for its consumer brands?” she asks. Another challenge for Pittie would be to take a call on advertising. “He is turning commodities into brands. So, one needs to advertise and create awareness eventually,” she says. Value-for-money consumers want to take home brands that are affordable as well as aspirational. They want to be seen with the visible brands.

Pittie, for his part, intends to stick to his game plan. “I don’t want to be on TV,” he says. But there are puja brands such as incense sticks on TV and with brand ambassadors. Moksh Agarbatti had Madhuri Dixit, Hari Darshan roped in Juhi Chawla, Zed Black flaunted MS Dhoni, and Cycle Pure managed to get Sourav Ganguly. Pittie, in contrast, wants to stay away from the herd mentality. “I have to balance cost and quality,” he says, adding that the money saved on advertising is passed on to the consumers. In terms of advertising, all the brands score high digitally. “My monthly advertising budget in quick commerce is quite high,” he claims, sharing his biggest challenge. “I need to stay true to the core: Value-for-money,” he says. There were times when Pittie rolled out premium products. But they bombed. “We don’t have that DNA. For me, gold lies at the bottom of the pyramid,” he signs off.