Rajkummar Rao

Rajkummar Rao

Image: Mexy Xavier; Hairstylist: Vijay Raskar; Makeup Artist: Nitin Purohit

Costume Stylist: Sanam Ratansi

The only time an actor can be himself is during interviews, says Rajkummar Rao, sitting down for a chat on a balmy November afternoon in Mumbai. Otherwise, he is always playing someone else on screen. Rao completes 15 years in the Hindi film industry in 2025, and says that he is now secure as an actor, but not satisfied. During this time, he has been part of films that made people think, and made bank for the makers. His debut, Dibakar Banerjee’s Love Sex Aur Dhokha (LSD) in 2010, was both a critically acclaimed film for its bold take on social ills, and a success at the box office. Fifteen years later, Rao also is enjoying both critical and commercial success at once. His career track record for 2024 is proof. The same, however, cannot be said for the Hindi filmm industry that he is part of. In 2024, re-releases like Laila Majnu, Tumbbad and Rockstar got more love from people than many of the creatively hollow, forgettable projects that released alongside them. According to Rao, this is a sign that we must value our writers more. It is time to focus on good writing, he says; create more opportunities to match the talent in independent cinema with the viability of powerful producers, and “see where it lands”.

Rao, a self-made actor, has always walked the talk when it comes to taking independent cinema and the mainstream hand-in-hand. While he made audiences laugh with a desi rendition of Rema’s Calm Down in the commercial entertainer Stree 2, he also did Anubhav Sinha’s Bheed (2023), which though a box office flop, was critically acclaimed for being a strong portrayal of the plight of migrant labourers during the Covid-19 lockdown, and the inherent class and caste conflicts in society.

Rao’s ability to pick “politically courageous films”, and his willingness to work in projects with a range of budgets has “brought out different aspects and strengths of his acting talent”, says Meenakshi Shedde, a film critic and curator who does South Asia programming for the Berlin and Toronto film festivals.

“Rajkummar, for me, is a key face of Bollywood 2.0. He represents artistes who help independent cinema survive under the force and weight of the mainstream,” Shedde adds, explaining that the industry needs both independent and big budget films if it has to thrive. While the latter tends to generate money and employment, the former tends to generate credibility and international representation in the festival circuits.

A Year of Achievements

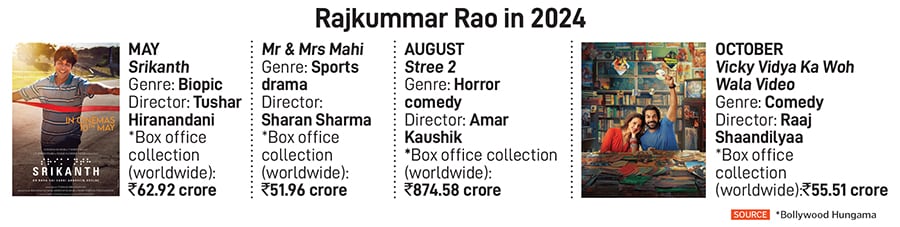

Rao was one of the most commercially successful stars in 2024. He started the year with Srikanth, the biopic of visually impaired entrepreneur Srikanth Bolla, founder of Hyderabad-based Bollant Industries. The actor had four releases in total (see box), which cumulatively posted over ₹750 crore of lifetime earnings at the box office in India, as per Bollywood Hungama.

The money haul was led by Amar Kaushik’s Stree 2, which contributed to ₹620 crore of those earnings, making it one of the highest grossing Indian films of the year. The worldwide box office revenue numbers stood at ₹874.58 crore for Stree 2 and ₹1,045 crore for all of Rao’s four films put together in 2024, as per Bollywood Hungama.

“We knew there were a lot of expectations from Stree 2 but for it to do the kind of business that it did was overwhelming,” says Rao. The actor does not see these numbers as burnishing ‘Brand Rajkummar Rao’ in the film industry. He claims, in fact, that he does not believe in the concept. “I am an artiste, not a commodity,” he says. “Being a film actor is all I’ve ever wanted since I was a kid, and now for me it is just about having fun.”

Stree 2, co-starring Rao, was one of the highest-grossing films in India in 2024

Stree 2, co-starring Rao, was one of the highest-grossing films in India in 2024

Intent & Passion

The Rajkummar Rao of today is able to buy a home in Juhu for ₹44-odd crore, and own luxury cars and bikes, but the actor did not grow up in money. He recalls his childhood as a time when his parents [his father was a government employee and his mother was a homemaker] struggled to make ends met. He lived in a joint family in Gurugram, the youngest of three siblings. Things were difficult but not dire, and the family found joy in small things, like watching movies over the weekend. This was how young Rao “got sucked into the world of films”. It was no surprise, then, that the boy who grew up internalising stories and characters that he saw on screen enrolled into the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune for an acting course in 2005. At this institute, whose alumni include veteran actors like Jaya Bachchan, Shabana Azmi and Naseeruddin Shah, Rao learnt “that acting is not just about looking a certain way or saying the dialogues, but about putting life and oxygen into a character”.

It is only when he talks about his craft, and the world building of characters, that Rao seems most enthusiastic. He speaks about artistic process with a depth that has become rare for actors these days. While he says the usual things like “going out of the comfort zone”, he stresses that he is a man with good intentions, and having the right intent in this business is all that matters.

On graduating from FTII in 2008, he rode his bike to Mumbai, and rented a flat in Andheri with two others. There was no strategy or plan, the actor says, because he struggled to convince people to let him audition for a good part. Many times, they would call him to just read one-odd line for an insignificant role. “You have to believe in what you do and keep going. I just kept doing my job, and that is what has worked for me,” says Rao. “People eventually see that intent, that sincerity and honesty in your work.”

It was this earnestness that perhaps convinced director Hansal Mehta to cast Rao in his 2012 film Shahid [about slain human rights lawyer Shahid Azmi], which got Rao a National Award. The film was shot on a shoestring budget, Mehta said in an interview with Siddharth Kannan. The director recalled how Rao borrowed shirts from people on set for many scenes. “Though I told him that I had enough money to buy shirts for him, Rajkummar insisted on doing this, saying that they would look worn and aged, and would complement his character well. That was some other level of dedication, thanks to which we managed to make the film at a budget of ₹35 lakh,” said Mehta, who went on to work with Rao in Citylights (2014), Aligarh (2015), Omerta (2017) and Chhalaang (2020).

People who have worked with Rao also point to the actor’s ability to immerse himself into a film. Amit Masurkar, director of the political satire Newton (2017), says it was easy for him to picture Rao as the naïve, stubborn government official who plays by the rules and is obsessed with conducting free and fair elections no matter what the obstacles. He remembers how Rao restyled his hair like physicist Sir Isaac Newton, whom his character in the film idolises.

On set, Masurkar says, the actor was focussed, but fun. “He is always in the zone, but doesn’t make a big deal out of it. Some actors stay in character throughout, but Raj is able to switch on and off. That’s a great talent.”

Also read: Rajkummar Rao: Bringing realism to the reel world

Shedde recollects that Rao was shy and nervous during the screening of Newton at the Berlin International Film Festival. “I think he had not really been to an international A-list festival before, and the thought of an international audience watching and commenting on his film made him anxious,” she says. “Newton questioned the idea of democracy itself. I told Rajkummar he had made a powerful film because he had faith in it, so all he needs to do is keep the faith.”

She feels that Rao could have had roles written for him, simply for his “daring” to take on projects that are not only politically and socially sensitive, but also require him to submerge into the character. “If you sign on a star, for instance, they come across as stars on screen even if they are really good actors, and tend to overpower the role,” Shedde says.

In the case of Srikanth, director Tushar Hiranandani was sure that only Rao could do justice to the role. He realised he was right when, during the course of preparation and shooting, Rao started looking and behaving just like the real Srikanth Bolla. The director says it was Rao’s idea to not make a pure vanilla biopic and add shades of grey to his character. This meant that while his character was a confident go-getter, he could also be vain, greedy and deceitful.

“Raj and I wanted the film to be different, so that the next time anyone makes a film about visually impaired people, they use Srikanth as a reference,” Hiranandani says. He adds that while Rao gave his inputs on scenes, he often went with the director’s vision. “Sometimes, I asked him to be a bit filmi in scenes. He does not like doing that, but went ahead with it and gave me what I wanted,” he says.

Rao says he understood long ago that a director’s vision matters the most for a film overall, so he trusts them to know best. This lesson came to him during a low phase. In 2017, he had delivered strong performances in films like Newton, Trapped and Bareilly Ki Barfi. Then, apart from Stree that came a year later, none of his films performed well at the box office. “Those [failed] films taught me that you can be the best actor in the world and tell a story however you want to, but if you don’t have a good director, you’ll never have a good film in your hand,” he says.

Rao admits that his profession can cause loneliness and anxiety, and credits his partner, actor Patralekhaa, for being his“biggest strength and support system”

Rao admits that his profession can cause loneliness and anxiety, and credits his partner, actor Patralekhaa, for being his“biggest strength and support system”

Against the Grain

Stars and conventional good looks drive the film industry, Shedde says. Rao’s big achievement, therefore, is how he has managed to build a career on the back of skills so strong that his lack of conventional good looks has become irrelevant. She points to how, with films like Shahid, Aligarh and Omerta, Rao’s work has frequently questioned our Islamophobia, our homophobia and many prejudices. “In Badhaai Do (2022), he played a homosexual cop embedded in the system. That is courageous on so many levels,” she says.

Rao says that while he tries to have fun with his roles, films like Shahid, Newton and Srikanth can be mentally draining. “It has happened that I have taken the characters back home subconsciously, without even realising it. Sometimes, it becomes so heavy that you start counting the days. You want to get out of the mind space because it is draining you out,” he says.

During difficult times, Rao is thankful for his partner, actor Patralekhaa, who is his “biggest strength and support system”. The profession can get cut-throat, he says, and cause a lot of anxiety and loneliness. “Patralekha has been with me since my first film. She is my anchor, the reason I like going back home after work because I find happiness and purity there,” he says.

Rao’s mainstream film choices have also been out of the ordinary, where he has taken on roles irrespective of their length, something else that does not come easily to many actors in the Hindi film industry. In The White Tiger (2021), for instance, he plays a secondary role to newcomer Adarsh Gourav, many years his junior. In Queen (2014), which was Kangana Ranaut’s show all the way, he plays the negative character with a few scenes.

Rao says that when he takes on a new project, he is concerned not only about what he needs to do as an actor, but the entire film. This can be the story, the creative vision of the director, and even the economics. “I can move on to something or the other as an actor, but if a big budget film fails, it is very risky for makers and difficult for them to bounce back. I would rather do films that have great stories, great actors attached to the project, and in the budget where everybody is happy making it. Nobody should be going through hell while making a film,” he says.

Actor Tripti Dimri, who starred alongside Rao in Vicky Vidya Ka Woh Wala Video last year, attests that Rao often takes initiative during shoots, rather than just being concerned about his role. “I remember one scene where he was not in the frame, and the assistant director told him to rest. He answered saying, ‘But I am in the scene, right? What do you mean by rest?’ That is the special quality about him.” Comedy is a difficult genre, but Rao made it look easy, Dimri says. “He is extremely secure as an actor, which is so important.”

Rao reiterates that he is secure, but not satisfied. He bought his Juhu home at an exorbitant price, for instance, to add to his motivation. His idol, actor Shah Rukh Khan, had told him that buying a home beyond his means would make him work harder because he would want to earn it. “I have never felt satisfied as an actor, and I hope that I never do,” Rao says.

He is now excited for the film Malik, which is an action genre that he has not done before. He would like to keep exploring new genres and characters, like a “hardcore love story”. He does not think too much about his prospects, and says he will never forget the reason why he became an actor. “I am the chosen one,” he says. “As long as I get to work every day, I am on a film set, surrounded by people passionate about cinema, figuring out how to explore a character, I’m very happy.”