(From left) John Dawber, corporate VP and MD, GBS, Novo Nordisk; Jay Doshi, MD and CIO, corporate units, BT Group; Jaya Jagadish, senior VP and country head India, AMD; Krishna Kumar G, MD, Harman India, and senior vice president, automotive R&D country lead; Pawan Choudhary, CTO, Zinnia India

The American police drama series Blue Bloods (2010), set in New York city, ran into 14 seasons by last year. About five minutes into episode 7 of Season 2, in a segment that highlights the perennial problem of budget cuts, Police Commissioner Frank Reagan—played by a macho looking Tom Selleck, waxed moustache and all—quips: “Let’s outsource 911 to Bangalore.”

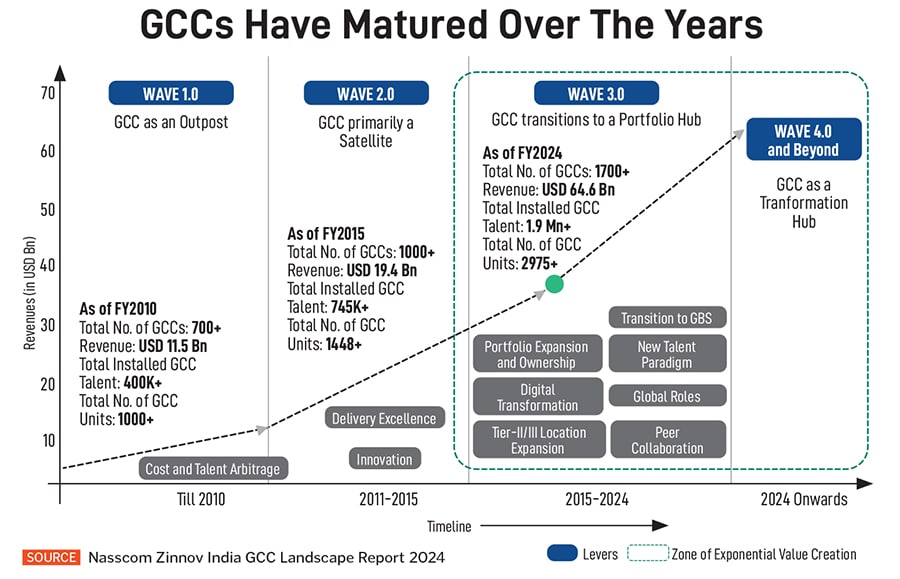

That was late 2011, three years after the global financial crisis. Today, even as India’s tech services giants such as Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) and Infosys expand their own innovation centres around the globe, their biggest customers are themselves seeing India in a different light. They are contributing to the build-up of a new wave of what have come to be known as Global Capability Centres or GCCs.

A simple definition of a GCC would be something like an in-house technology-enabled facility of a multinational company, but not one set up as a services provider to other customers. One of the biggest examples would be the American banking giant JPMorgan Chase’s 55,000-strong presence in India. The bank is headquartered in Reagan’s New York.

JPMorgan expects to ramp up its Indian GCC staff by 5 to 7 percent annually over the next few years, Reuters reported in May 2024, citing Deepak Mangla, CEO of the bank’s corporate centres in India and the Philippines.

Overall, some 1.9 million of India’s IT and IT-enabled services workforce already work at the GCCs, according to the latest estimate by the National Association of Software and Services Companies (Nasscom), the industry’s biggest lobby.

Historically, these centres were established for back-office support for finance and HR, and other admin support, or for tasks such as software testing. Today, a fast-growing proportion of that workforce is responsible not for backend support, but advanced engineering R&D and innovation, and front-end development of products.

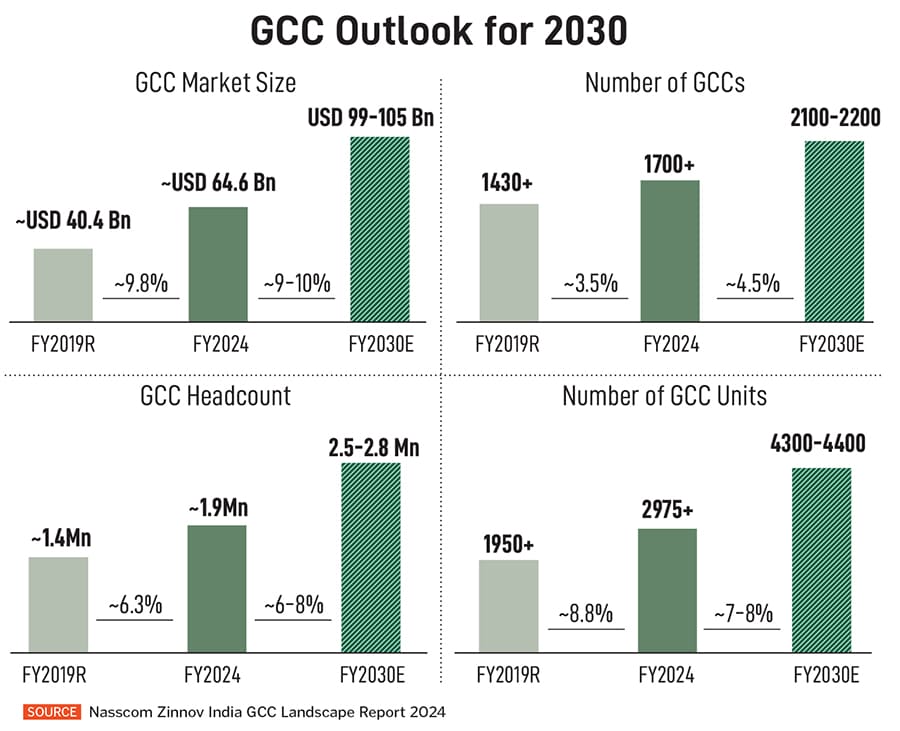

Overall, Nasscom projects the number of GCCs in India to increase from about 1,700 in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2024, to 2,100 by 2030, spread across Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, Mumbai-Pune and Delhi-NCR. These centres are expected to expand their units into India’s Tier II cities as well, where they already have a small presence today.

Overall, Nasscom projects the number of GCCs in India to increase from about 1,700 in the fiscal year ended March 31, 2024, to 2,100 by 2030, spread across Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, Mumbai-Pune and Delhi-NCR. These centres are expected to expand their units into India’s Tier II cities as well, where they already have a small presence today.

GCCs accounted for a $64.6 billion share of India’s $250 billion IT services and ITES exports in FY24. And within that, engineering R&D services accounted for $36.4 billion for FY24, according to a September 2024 report titled ‘The India GCC Landscape Report’, commissioned by Nasscom and put together by the consultancy Zinnov. It projects India’s GCC exports at $105 billion by 2030.

These centres come in all kinds of configurations, and are often not even seen as GCCs by the parent companies—from chipmaker AMD’s global R&D centre in Bengaluru, its biggest anywhere in the world, including the US, to the small teams that software companies such as ThoughtSpot and Zinnia have in locations such as Thiruvananthapuram and Nagpur, respectively.

And they represent every vertical and horizontal one can think of—from the large financial companies, with their massive centres, to drug companies such as Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly—which has just announced its plan for a second GCC facility in India—and Harman’s 4,000-strong automotive specialists to niche players such as San Francisco-headquartered ‘media intelligence’ provider Meltwater’s brand new R&D centre in Hyderabad.

For a sense of how far some of these companies have come in tapping their India teams, consider what AMD’s Country Head Jaya Jagadish has to say: “Right now we have the ownership of one of our roadmap cores, and the entire team will be working on it.” Jaya is referring to a mainstream CPU product that AMD is looking to commercialise in under three years. The company has achieved this in the 20 years that it’s been present in India, and in the world of semiconductors, where the smallest of mistakes can derail entire projects, that’s a remarkable feat.

And Jaya and her team’s energy is palpable. “We’ve just gotten started (on the new core) and that’s hugely exciting. I mean, after 20 years, that feels like a great milestone.”

At ThoughtSpot, a search and AI-based business analytics provider, one of the youngest companies in this series, Country Head and VP of Engineering Kumar Gaurav is positive about being able to go beyond Bengaluru to locations such as Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala. ThoughtSpot originally got a small team there when it acquired a company called Diyotta.

Today, “much of our front-end development at this point happens from there”, Gaurav tells Forbes India. He adds: If one takes a quick look at the company’s eponymous product, its core value proposition is, how can it help a user search structured data, and the insights that can support decisions and actions. “So, visualisation creates a very powerful story on this entire piece.”

Experts like Gaurav call it ‘charting’. It needs to be instantaneous—fast loading and efficient. And how useful the chart will be for the end user hinges on ground-up innovation, and ThoughtSpot has its own charting libraries as well, he says. “Many of these things are powered by our engineers in Thiruvananthapuram,” he adds.

ThoughtSpot, founded in 2012 by Indian-American entrepreneurs Ajeet Singh and Amit Prakash, has been in India since 2017. In September 2022, the company announced a $150 million plan to significantly expand its India development centres. CEO Ketan Karkhanis tells Forbes India he wants to “double” the company’s team in India.

The cost advantage multinationals seek in coming to India and other cheaper locations remains an important factor. In a recent survey by the advisory firm ISG, 58 percent of enterprises still rated ‘reduced staffing costs’ among their top three reasons for wanting to go the GCC route. However, 26 percent of them also placed ‘improved innovation and collaboration’ among their top three reasons to build or expand GCCs.

The experience at Harman bears this out. A company famous for its high-quality infotainment systems, Harman’s automotive GCC in Bengaluru is deeply integrated with the parent, top executive Krishna Kumar Gopalakrishnan tells Forbes India. Krishna is managing director, Harman India, and senior VP, automotive R&D country lead, at the Samsung company.

The GCC’s Bengaluru teams are working on every line of business for Harman, he says. “We have end-to-end capabilities here,” Krishna says. “From ideation to product management, requirements management, system definition, architecture design and so on, you name it… we have relevant, highly qualified and skilled people in India.” He adds: “The cost arbitrage is important, but we are there through the length and breadth of everything that Harman does today.”

At ThoughtSpot, CEO Karkhanis says: “We have a different mindset (versus cost arbitrage). India isn’t an innovation centre for us, but an innovation powerhouse.” And “think of ThoughtSpot as a company with two global headquarters. One in Mountainview (California) and the other in Bengaluru”.

Also read: We now own a next-gen roadmap core: AMD’s Jaya Jagadish

OGs of GCCs

If one digs deeper, it becomes clear that looking at this only through the lens of cost savings is unfair to the pioneers who helped lay the foundations of this industry in India. While stories about the founders of India’s IT services giants such as Infosys or Wipro are well known, credit also goes to those who championed the capabilities of India-based talent from the inside, within the multinational companies that they worked for. People like Dinesh Paliwal, former CEO of Harman, now a partner at the private equity firm KKR, or Sachin Lawande, former CTO at Harman, the CEO at Visteon Corp, a well-known American automotive electronics company, for instance.

Another such name is Jaswinder Ahuja, corporate VP and India managing director at Cadence Design Systems. Cadence is best known for its software and hardware tools used in the design of integrated circuits, systems on chips, and electronic systems—broadly described as electronic design automation or EDA technologies, which help engineers design, verify and test complex semiconductor devices.

Early in his career, nearly 40 years ago, Ahuja was among the first engineers at Gateway Design Automation, the company that invented Verilog, one of two main hardware description languages used to this day by chipmakers such as AMD. “We were all driven, ambitious out there to prove ourselves, saying we are as good,” Ahuja recalled in an interview with Forbes India. “And so, we hustled a lot to convince the management at the headquarters to get us involved in other mainstream projects.”

By the time Cadence acquired Gateway in 1989, Ahuja was part of a small team at GDA’s India centre, which led to what’s today one of Cadence’s largest overseas establishments. Cadence has more than 4,200 employees in India spread over five locations.

That represents a third of the company’s total headcount and not far from 40 percent of its R&D resources, Ahuja says. “We are the OGs of GCCs. We are heavy on engineering and light on the corporate functions, if you will, in India.”

AI Leapfrog Opportunity

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) in the form of generative AI are other factors that will influence the future of GCCs in India, says Sunil Gopinath, CEO of Rakuten India, the Indian unit of the Japanese ecommerce, internet and telecom group Rakuten.

Gopinath is also executive officer at Rakuten Inc. And he oversees some 2,000 people delivering software development and innovation from Bengaluru for Rakuten’s internet businesses. A separate team works on the telecom side. Overall, Rakuten has close to 4,000 people in India.

The use cases of AI that can come out of India’s immense scale and diversity will be globally relevant, he says. These AI applications have to work for a billion people and address diversity of language, culture, physical distance and location, and so on. “So, anything we build for India, just the experiences that the team here gets from doing that for AI… that can be easily translatable to anywhere else in the world,” Gopinath says, be it Mexico or South America, or South Africa.

In the process, India will develop so much expertise in AI that even though the US has taken the lead with companies such as OpenAI, over the next few years, because of its talent base, “India has an opportunity to leapfrog”. And within the GCCs, the knowhow that’s generated will be relevant for the parent company’s global business, he adds.

Therefore, Gopinath sees today’s mature GCCs evolving further to take greater ownership of products. “Over time, we will mature to the point where, within the company, for services that we provide to the company, there will be a lot of ownership of the products.”

This will mean that in the foreseeable future, product definition, business strategy and even execution, R&D and implementation, “everything will be done from here”. Sales can happen wherever the market is, be it the US or Japan or China or Taiwan, he says.

This all makes sense because the experience has reached a point where there’s no need to break down one product portfolio into multi-site development, which has its own challenges. Eventually organisations with mature GCC experience will decide on clear product lines that can be delivered end-to-end from India or China and so on, he says.

Another “transformation” is illustrated by Rakuten’s experience with its SixthSense platform. This is a “unified observability platform” which helps businesses monitor their cloud infrastructure and software. Rakuten India played a key role in developing this, initially for internal use, but now even in India several external enterprise customers are using it.

“This opens up a fantastic frontier for us, where products will be built ground-up from India. It’s almost like an intrapreneurship opportunity,” Gopinath says.

Also read: ‘There are areas where India will lead AI innovation’: Christopher Young, Microsoft

Multipolar World

There are macroeconomic and geopolitical factors too that might align to make India an attractive destination for hi-tech centres. “Definitely, we are moving towards a multipolar world. And nationalism is on the rise around the world,” Ahuja at Cadence points out.

Supply chains have been disrupted, starting with what happened during the pandemic, and further amplified by geopolitical tensions between the US and its allies on the one side and China’s superpower aspirations and Russia’s militaristic bid to reclaim that status on the other.

Supply chains have been disrupted, starting with what happened during the pandemic, and further amplified by geopolitical tensions between the US and its allies on the one side and China’s superpower aspirations and Russia’s militaristic bid to reclaim that status on the other.

As a result, “one of the trends that’s emerging is a coalition of trusted partners”, Ahuja says.

In every area, be it supply chains or national security—not just defence but also energy security, and supply chain security for critical technologies and components—and the debate around globalisation and deglobalisation, there isn’t an easy answer to any problem today, he points out. “No nation on the planet can be self-sufficient. It’s not going to happen. It’s not the US. It’s not the entire Europe put together,” he says.

Countries need to work together, and a globalisation 2.0 is emerging, built on this coalition of trusted partners, where both multilateralism and bilateral ties will coexist, he says.

And India has credibly positioned itself as a trusted partner, through efforts like its leadership at the G20 and as the voice of the Global South in various forums, he points out.

If one looks at a cross section of the GCCs, while most tie back to US parent companies, there are also GCCs of multinationals from Britain, Europe, Japan, South Korea and Australia. “They represent the globe in some sense, right?” he asks.

In the near term, what US President Donald Trump will do with tariffs and restrictions has become a hot topic of conversation from drawing rooms to Davos. Trump has in the same breath called Indians the smartest people and serious abusers of America’s legal system, a system which underpins its entrepreneurial culture like nowhere else in the world.

Will he make it tougher for US corporations to send higher value jobs to India? The coming weeks and months will reveal. However, political and business analysts have also described him as more “transactional” than his predecessor, meaning he might be willing to give in return for getting what he deems as his due or America’s due.

That apart, many nations in the US-led grouping will choose to work together in the emerging world order, Ahuja says. And India can be a common factor, a common destination as such relationships grow. This augurs well for the future of the GCC sector in India. It holds the promise of playing an ever more significant role in evolution of the technology landscape globally and contributing to it.

Sponsorship for Scale

While Gopinath’s assessment holds true for the more mature GCCs, be it at Rakuten, Harman or AMD’s global R&D centre, overall, the sector has a long way to go.

For example, only 33 percent of the Fortune 500 companies currently have a GCC in India, according to Avasant, a management consultancy. And the experience so far shows that most GCCs that start out in India do not achieve real scale, Avasant pointed out in a report in December 2024.

Avasant counts more than 1,750 GCCs in India. Only about 5 percent of those have a headcount exceeding 5,000 employees and the median headcount is only about 400, indicating that many centres operate on a relatively smaller scale. Even among the biggest companies, the median GCC headcount is around 1,550, according to Avasant’s report.

One factor that will continue to influence the future of this sector is executive sponsorship at the corporate level in the parent organisations, says Kamal Karanth, co-founder and CEO of Xpheno, a staffing provider in Bengaluru to many multinational GCC clients. “It is one thing to set up a GCC and quite another to continuously back them,” he says.

Nine out of 10 times a multinational company considering a GCC in India would have already experienced offshoring either via multinational services providers such as Accenture, IBM or Cap Gemini or India’s TCS, Infosys or Wipro.

The difference is, as a GCC, they will be coming to India for the first time as an independent legal entity, Karanth points out.

And such entities will only succeed in the long run if there is continued support from home, be it New York or London, Sydney or Tokyo. It’s a fact of life for corporate-level leadership to keep changing and there’s no guarantee that an incoming chief information officer, for example, will see the India centre in the same favourable light.

Karanth recalls how this happened with one of his clients where a GCC, which had plans to ramp up its staff 5x, stagnated after a new CIO took over at the company’s headquarters. “The single largest factor is not even talent, it’s continuity of sponsorship. Will they continue to see the India GCC as a strategic entity” for the global operations of the parent, he says.

The Time is Ripe

And the time may have come for that to happen. At Nasscom, the effort to promote these centres started with the Nasscom captive council initiative in 2010, says COO Sangeeta Gupta. Then the name changed to GIC, or global in-house centres, and then eventually rechristened as global capability centres or GCCs around 2016, at a Nasscom meeting, Gupta says.

Since then, the ecosystem has matured, and Nasscom continues to help both existing and incoming companies with several initiatives. This ranges from sharing experience to promoting industry-oriented skilling in colleges to engaging with top government officials on policies related to what is known as ‘transfer pricing’ and how GCCs are taxed in the country.

Some GCCs have also successfully collaborated with India’s growing tech-startup ecosystem.

“Today, every state government is talking GCC, the central government is talking GCC. It’s been a long journey, and the time is now,” she says.

“For us it’s an exciting time to be in India and Bengaluru,” John Dawber, corporate vice president and managing director, global business services at Novo Nordisk, tells Forbes India. Dawber leads a 4,400-strong GBS (Global Business Services) out of Bengaluru that has most of the multinational drug company’s value chain represented within it.

The maturity level of the GCC and the growing innovation and startup ecosystem in India are all coming together, he says. “The time is ripe,” to do work out of India that makes a significant difference to Novo Nordisk’s business worldwide, he adds.

For now, in some areas such as fintech, for example, it’s not immediately apparent as to how a company such as Novo Nordisk might take advantage of the innovation or the talent available in India, he says. The company has done some work on a fintech tool. However, translating such experience to a real-world pharmaceuticals tool “is perhaps where we sometimes meet some challenges”, he says.

And it’s a long way to go for the entire GCC sector.

From a products portfolio perspective, the “what, why and when is decided at the headquarters”, while more of the “who and how” is happening at the GCCs, Ahuja at Cadence says. And this is broadly true of other maturing GCCs as well.

The aspiration is that more of the “why”, the upstream decisions, should also be made in India. What’s needed for that is the ecosystem, proximity to customers, and deep understanding of the needs in the semiconductor world, in Cadence’s case.

And be it at Cadence or the India GCCs of many of its customers—from Texas Instruments to Nvidia—engineers can see the gradual maturing of the ecosystem and take back news to their respective product marketers about new projects that have brought more of the higher value work to India.

There is the opportunity to work together with customers and ecosystem partners in India and learn from them. Fast forward five or 10 years, then the Indian centres should be in a position to make decisions on some of the product portfolios as well, he says. “We are not there today, but that’s both the aspiration and the opportunity,” he says.