In January 2015, Ajay Singh was gripped with a sense of déjà vu. SpiceJet was on the ventilator.

“Can you revive it?” stuttered the head of a merchant bank on the other side of the phone, failing to mask his anxiety about his investments in the low-cost airline.

The previous month, SpiceJet, the airline Singh founded by buying a defunct ModiLuft in 2004 and renaming it a year later, had been abruptly grounded. It had run out of money, having posted losses in three consecutive years. In 2013-14 (FY14), the losses ballooned almost five times to ₹1,003.24 crore, compared to the previous year. Its debt had reached staggering levels.

“When I left, it (SpiceJet) had ₹700 crore in cash. By January 2015, it had liabilities of ₹3,500 crore,” says Singh in an interview with Forbes India. He had left it in 2010, when Kalanithi Maran, chairman and managing director of the Sun Group, bought the airline from American private equity firm Wilbur Ross and the United Kingdom-based Kansagra family.

Sure enough, in 2015, he was back to cradling his baby, thanks to his record of turning around Doordarshan (DD) and the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC). The bankers bet on him and were rewarded for their confidence with 17 consecutive quarters of profitable growth.

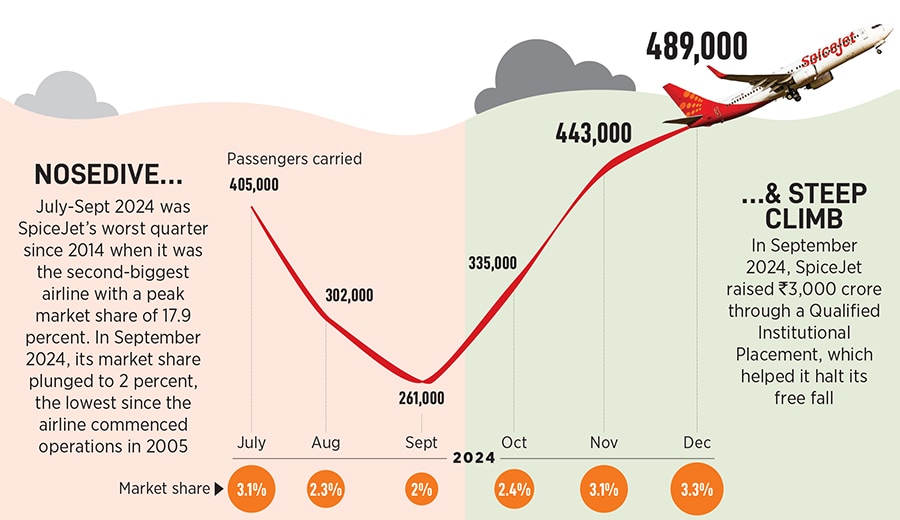

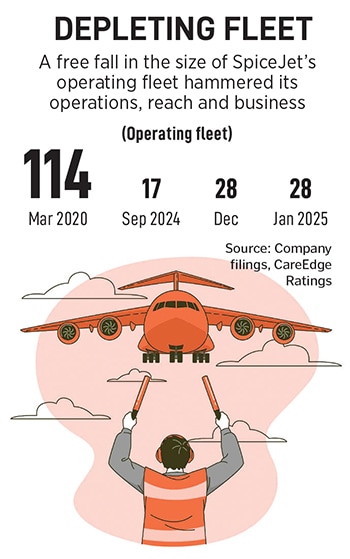

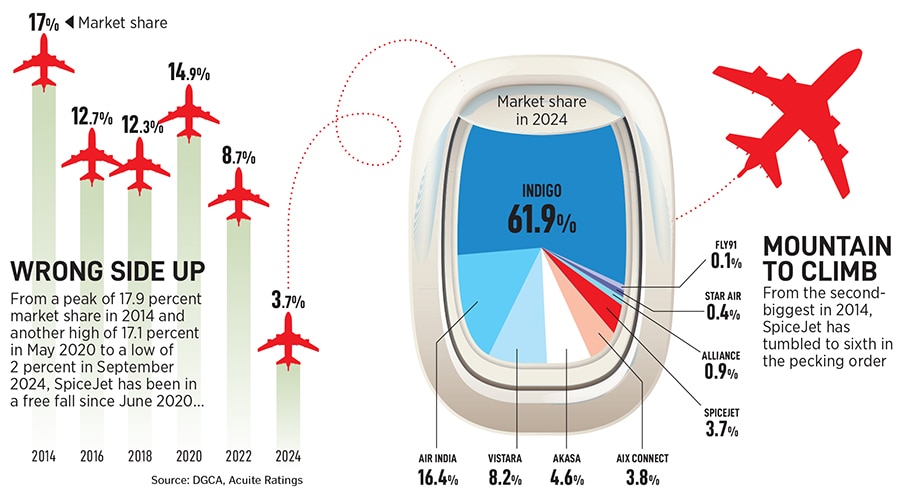

But it was not meant to last. From 17.1 percent in May 2020, SpiceJet’s market share dipped to 2 percent in September 2024. Its fleet of operating aircraft was down to 17 from a high of 114 in March 2020.

Singh was again possessed with déjà vu. “I couldn’t let it die,” he says. “This is an airline that refuses to die. We won’t die,” he adds.

What egged him on were the jibes of naysayers. “How can you survive with just 17 aircraft?” they said. “You won’t be able to pull it off this time.”

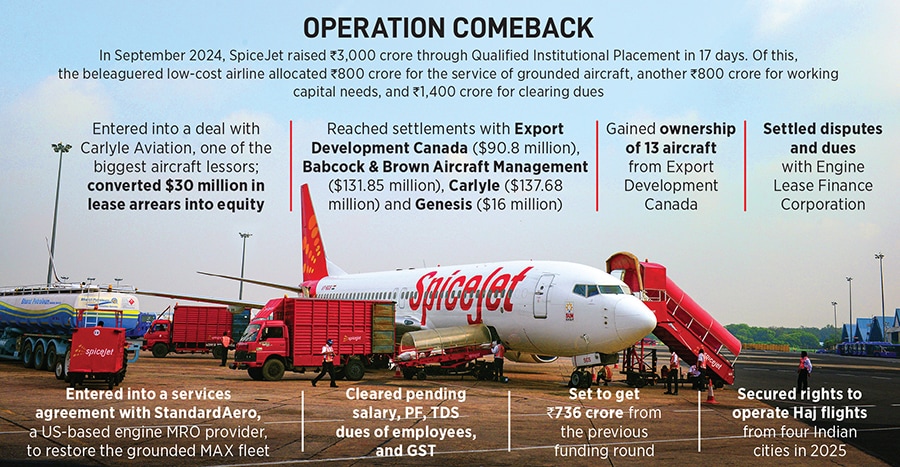

Almost inevitably, Singh resolved to prove them wrong. In September last year, he raised ₹3,000 crore through Qualified Institutional Placement (QIP) in just 17 days. He allocated ₹800 crore for the service of grounded aircraft, another ₹800 crore for working capital, and ₹1,400 crore for clearing dues. Over the next quarter, he signed a bunch of deals to clean his stable (see box). Within three months, the fleet inched up to 28. “We will take it to 35 by April this year,” he says, adding that the airline ended the year with a 3.7 percent market share.

Can he do the unthinkable once again?

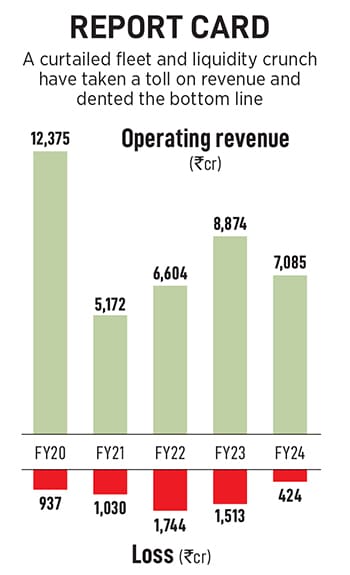

It is not going to be easy. A report by ratings firm CareEdge says: “Losses over the years have significantly eroded the company’s net worth.” Though the airline has used the QIP money to clear its dues and get back in shape, a turnaround in net worth depends on its ability to sustain profits. “The company has total debt of ₹5,379 crore on March 31, 2024, of which lease liability was ₹4,227 crore,” says the report released last month.

Lost and Found

In 2010, Singh did not want to sell. “I never wanted to sell my baby,” he recounts. His options were limited by an unprecedented rise in aviation fuel price, which, in turn, had dented SpiceJet’s bottom line, pushing losses up from ₹70.74 crore in FY07 to ₹376.38 crore in FY09. The operating revenue, though, was going the other way: From ₹640.44 crore to ₹1,689.45 crore during the same period.

“We just needed to hang in. I knew we would manage to fly out of losses,” he says.

The investors did not agree. They sold their stakes. Singh, too, exited.

Five years later, he received a call from the anxious banker mentioned above. “Can you do it?” the banker asked. Apart from Singh’s role in turning around DTC and DD, the banker was also impressed by his involvement in the National Telecom Policy and Information Technology Act in 1998-99. Those were during his years of political activism.“I wanted to be in public service,” Singh says.

That ambition came crashing down when the Bharatiya Janata Party lost the 2004 Lok Sabha election. Singh was blamed for the ‘India Shining’ campaign, which was seen to be disconnected from the reality at the grassroots. “That was the first big setback and failure in my life,” he recalls.

Six years later, in 2010, came another setback when SpiceJet was sold. Though the blow was devastating, Singh lived to fight another day. “I am an eternal optimist. kuchh na kuchh to ho jayega. Kuchh na kuchh to kar lenge (I always feel that something will work out. I will do something),” he says.

Something did happen in 2015, when he was called upon to revive SpiceJet.

What If

After regaining control, Singh bet big on his most enticing pitch for stakeholders: ‘What if’.

He organised a flurry of townhalls with employees and underscored one message. “If we fail, nobody will blame us. Everybody knows it is an impossible task. But what if we revive SpiceJet? What if we turn this around?”

He organised a flurry of townhalls with employees and underscored one message. “If we fail, nobody will blame us. Everybody knows it is an impossible task. But what if we revive SpiceJet? What if we turn this around?”

He implored everyone to focus on the upside. The employees bought into his optimism.

The debtors and lessors, too, fell in line. Singh told them: “What will you get if the airline goes for bankruptcy? Nothing! Zero!” He laced his pep-talk with realism and tried to remove the biggest obstacle in scripting a turnaround. “If we lose, you also lose. But what if we win?” he told the embattled creditors and dangled the bait of clearing all dues in three years. They agreed.

What ensued was nothing short of miraculous. SpiceJet posted 17 consecutive quarters of profitable growth. “We returned the money in two years,” says Singh.

In 2020, SpiceJet became the second biggest airline after IndiGo. “We were flying high,” he recalls. The airline had a 17.1 percent market share in May 2020.

Then came the pandemic. And everything came crashing down.

Also read: Indian aviation sector in 2025: Airlines face headwinds

What’s This!

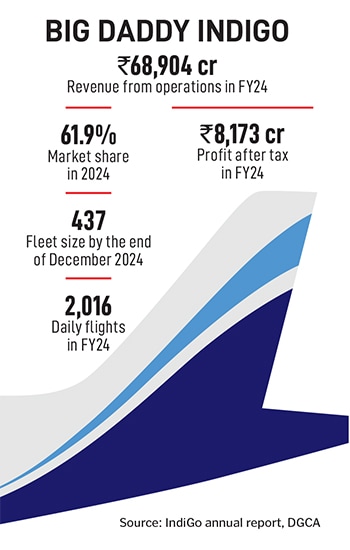

Fast forward to September 2024. SpiceJet’s market share plummeted to 2 percent. It went from being the second biggest airline in India to sixth. IndiGo had 63 percent, Air India 15.1 percent, Vistara 10 percent, and Akasa—the newest kid on the block—was ahead of SpiceJet for the second consecutive quarter with 4.4 percent, according to a traffic report by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA).

What made things worse was the depletion of its fleet. The airline was close to running out of money. A near-death scenario loomed. Detractors sharpened their knives.

What made things worse was the depletion of its fleet. The airline was close to running out of money. A near-death scenario loomed. Detractors sharpened their knives.

It was then that Singh pulled the QIP out of his hat. “We have survived, and now it is a turnaround-in-progress,” he says.

In October last year, a month after the successful QIP, the DGCA removed SpiceJet from “enhanced surveillance”, under which it was placed in view of the financial constraints that “could potentially affect discharge of mandatory obligations of aircraft maintenance”. After 266 spot checks, the regulator said in a press release: “It has been ensured that deficiencies and findings found during the spot checks have been subject to suitable rectification action by the operator. In light of the same and the financial infusion of additional funds into the company, SpiceJet has been taken off the enhanced surveillance regime.”

In October last year, a month after the successful QIP, the DGCA removed SpiceJet from “enhanced surveillance”, under which it was placed in view of the financial constraints that “could potentially affect discharge of mandatory obligations of aircraft maintenance”. After 266 spot checks, the regulator said in a press release: “It has been ensured that deficiencies and findings found during the spot checks have been subject to suitable rectification action by the operator. In light of the same and the financial infusion of additional funds into the company, SpiceJet has been taken off the enhanced surveillance regime.”

But the air pocket of debt that lies in wait offers him no respite. The second big challenge is the liquidity constraint. Though it raised ₹3,000 crore in September 2024, it would need more. Add to that the headwinds arising from exposure to fuel prices and foreign exchange rates, which have seen the rupee touch historic lows.

Over the five fiscal years through FY24, points out the CareEdge report, SpiceJet has been reporting operating losses, which are estimated to continue in FY25 (see box). Initially, operating profitability was affected by a spike in fuel costs and adverse forex rate, leading to higher lease rental outgo, and other dollar-dominated expenses, the report explains. The heavy dependence on Boeing does not help. Boeing constitutes a majority of SpiceJet’s fleet, while IndiGo has Airbus. Boeing has been grappling with operational issues for over five years.

Fortunately for Singh, people have learnt not to rule out a comeback by him.

Debilitating Blow

“He (Singh) has revived the company in the past. He is best suited to do so now,” says Sanjay Dangi, director at Authum Investment & Infrastructure, one of the institutional investors that participated in SpiceJet’s QIP in September. The airline’s operational issues, he asserts, have a lot to do with a series of external factors.

The biggest setback, Dangi points out, was the global grounding of the Boeing 737 Max aircraft in March 2019, triggered by two crashes. In October 2018, a Lion Air MAX plane crashed in Indonesia, killing all 189 on board. Five months later, an Ethiopian Airlines MAX crashed, killing all 157 on board. In March 2019, SpiceJet had to ground 13 Max aircraft, which reduced its fleet to 76.

This was a debilitating blow. In June 2017, SpiceJet ordered up to 205 planes from Boeing. “Around 150 planes were supposed to come by 2024,” Singh says. “This would have given us some ₹12,000 crore in cash in our bank,” he says, alluding to how the dynamics work in a ‘sale-and-leaseback model’ used by most airlines for buying aircraft. Under it, an airline buys an aircraft at an attractive price, sells it to a lessor, and leases it back for its use.

Sale-and-leaseback, Singh points out, generates cash and helps airlines with fleet flexibility. The grounding of Max in March 2019 changed that math. “Was the grounding of Max my fault? Who could have factored in such a thing?” he asks.

Silver Linings

Amid the gloom, Singh was looking for a silver lining. He found it in the troubles of rival airline Jet Airways.

In April 2019, Jet had suspended its operations. Singh once again played the ‘what if’ card with a long list of debtors and lessors of Jet and managed to add 32 of Jet’s aircraft to his own fleet. He bought time from the debtors and promised to return their money soon. “We continued. We survived,” he says.

A few months later, in March 2020, came the Covid-19 pandemic. Travel and hospitality industries were devastated, flights were grounded, and it seemed like the end of the world.

Singh, looking for a new beginning, converted his planes into cargo carriers and started making money. “We did ₹3,000 crore in business in cargo,” he says. The money was used to pay salaries, to sustain operations and to survive.

The survival, though, came at a cost.

Two years later, as the world was coming out of the pandemic, there was a massive rebound in the travel business. The debtors and lenders came calling. Singh was barely surviving and could not clear the dues. The rising oil prices also added to his woes. His aircraft began to get grounded.

“There was non-payment of dues to lessors and lack of maintenance on aircraft due to financial constraints and non-availability of components and spare parts,” highlights CareEdge in its report.

“There was non-payment of dues to lessors and lack of maintenance on aircraft due to financial constraints and non-availability of components and spare parts,” highlights CareEdge in its report.

Singh points to the cruelty of the external factors. “Was Covid my fault? A fuel price hike was not under my control,” he says. “I could only worry about the things under my control.”

Industry experts empathise with him. “He had a dream run from 2015 till the Boeing crash. SpiceJet went to over 100 aircraft in just four years,” says Kapil Kaul, CEO of CAPA India, an aviation consulting firm. “You can’t blame him for his position.” What is remarkable about Singh, Kaul contends, is his resilience. “He never gives up. He finds a way to survive,” he says.

As things stand today, Singh is busy doing the things that are under his control. He has raised money, is clearing the mess by settling dues, and is ready for his next flight.

“You can’t do much about the cards you have been dealt with. You need to focus on your hand,” he says, alluding to his umpteen efforts in pulling himself out of troughs over the last two decades. Though he admits that he has made his share of mistakes, Singh reckons he cannot rewire himself to look at the downside. “You might say that not building a cash reserve was a mistake, but who could have foreseen the 737 crashes?” he adds.

So, are the detractors correct in their assessment that Singh’s habit of ignoring the downside has often put SpiceJet on a sticky runway?

Surprisingly, Singh agrees. “The critics are right. Maybe somebody else in my place would have planned for a downside. It is possible,” he confesses, adding that he has been hunting for an able replacement, but has had no luck so far. “I can either put people around me or replace myself. But I need to do this at some point in time,” he says.

The airline might eventually get a new CEO, but the brand will always retain its core. “I could have shut. But I can’t shut down. That’s not in my DNA,” he says, pointing out that a few airlines went out of business over the last few years, such as Kingfisher, GoAir and Jet Airways. Aviation, he reckons, is a tough business. “But if you do it right, it is a great business to be in.”

So, is this the last time the world is witnessing SpiceJet attempting a comeback?

Singh smiles. “With every comeback, you hope there won’t be the next setback,” he says. He prefers to focus on his efforts rather than on monickers that the world has bestowed on him. “If there is one word that describes me, it is survivor,” he says. SpiceJet, he stresses, is an airline that refuses to die. “We won’t die. We will survive. We will fly.”